Two abstracts attempt to provide guidance to these important questions to reduce the toll of STEC.

FAO and WHO conclude shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infections are a substantial public health issue worldwide, causing more than 1 million illnesses, 128 deaths and nearly 13 000 Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) annually.

FAO and WHO conclude shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infections are a substantial public health issue worldwide, causing more than 1 million illnesses, 128 deaths and nearly 13 000 Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) annually.

To appropriately target interventions to prevent STEC infections transmitted through food, it is important to determine the specific types of foods leading to these illnesses.

An analysis of data from STEC foodborne outbreak investigations reported globally, and a systematic review and meta-analysis of case-control studies of sporadic STEC infections published for all dates and locations, were conducted. A total of 957 STEC outbreaks from 27 different countries were included in the analysis.

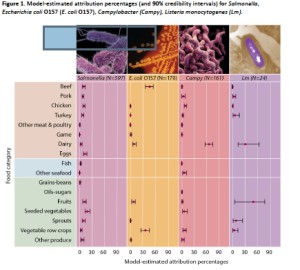

Overall, outbreak data identified that 16% (95% UI, 2-17%) of outbreaks were attributed to beef, 15% (95% UI, 2-15%) to produce (fruits and vegetables) and 6% (95% UI, 1-6%) to dairy products. The food sources involved in 57% of all outbreaks could not be identified. The attribution proportions were calculated by WHO region and the attribution of specific food commodities varied between geographic regions.

In the European and American sub-regions of the WHO, the primary sources of outbreaks were beef and produce (fruits and vegetables). In contrast, produce (fruits and vegetables) and dairy were identified as the primary sources of STEC outbreaks in the WHO Western Pacific sub-region.

The systematic search of the literature identified useable data from 21 publications of case-control studies of sporadic STEC infections. The results of the meta-analysis identified, overall, beef and meat-unspecified as significant risk factors for STEC infection. Geographic region contributed to significant sources of heterogeneity. Generally, empirical data were particularly sparse for certain regions.

Care must be taken in extrapolating data from these regions to other regions for which there are no data. Nevertheless, results from both approaches are complementary, and support the conclusion of beef products being an important source of STEC infections. Prioritizing interventions for control on beef supply chains may provide the largest return on investment when implementing strategies for STEC control.

Second up, in 2016, we reviewed preventive control measures for secondary transmission of Shiga-toxin producing Escherichia coli (STEC) in humans in European Union (EU)/European Free Trade Association (EEA) countries to inform the revision of the respective Norwegian guidelines which at that time did not accommodate for the varying pathogenic potential of STEC.

We interviewed public health experts from EU/EEA institutes, using a semi-structured questionnaire. We revised the Norwegian guidelines using a risk-based approach informed by the new scientific evidence on risk factors for HUS and the survey results.

We interviewed public health experts from EU/EEA institutes, using a semi-structured questionnaire. We revised the Norwegian guidelines using a risk-based approach informed by the new scientific evidence on risk factors for HUS and the survey results.

All 13 (42%) participating countries tested STEC for Shiga toxin (stx) 1, stx2 and eae (encoding intimin). Five countries differentiated their control measures based on clinical and/or microbiological case characteristics, but only Denmark based their measures on routinely conducted stx subtyping. In all countries, but Norway, clearance was obtained with ⩽3 negative STEC specimens. After this review, Norway revised the STEC guidelines and recommended only follow-up of cases infected with high-virulent STEC (determined by microbiological and clinical information); clearance is obtained with three negative specimens.

Implementation of the revised Norwegian guidelines will lead to a decrease of STEC cases needing follow-up and clearance, and will reduce the burden of unnecessary public health measures and the socioeconomic impact on cases. This review of guidelines could assist other countries in adapting their STEC control measures.

Mapping of control measures to prevent secondary transmission of STEC infections in Europe during 2016 and revision of the national guidelines in Norway

Cambridge University Press vol. 147

- Veneti(a1)(a2), H. Lange (a1), L. Brandal (a1), K. Danis (a2) (a3) and L. Vold

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0950268819001614

https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/epidemiology-and-infection/article/mapping-of-control-measures-to-prevent-secondary-transmission-of-stec-infections-in-europe-during-2016-and-revision-of-the-national-guidelines-in-norway/1990D2338B220F80F0E683DF6F622A40