Amy has survival skills. She knows how to field-dress animals. And has pretty good bowstaff skills.

Amy has survival skills. She knows how to field-dress animals. And has pretty good bowstaff skills.

At Tom Prince’s farm 20 miles west of Indianapolis, a Muslim man kneels over a goat, says a brief prayer, then cuts the animal’s throat. It’s hard to imagine a greater cultural mishmash than the early morning gatherings that take place here every Friday and Saturday.

Tim Evans, who reports for The Indianapolis Star, writes in USA Today this morning that since 1999, Prince has operated a self-service slaughterhouse that specializes in providing goat meat to the Indianapolis area’s growing international community. His card reads "You Buy — You Kill — You Dress — You Take Home," and business is booming. Prince also sells lamb and sheep, but goats are the big seller.

Prince, 80, runs the facility from 7 a.m. to 1 p.m. every Friday and Saturday, selling an average of about 50 goats per weekend. In the weeks before Muslim and other religious holidays, he says, sales often double.

The story provides an excellent overview of several facets of the intersection between food, language and culture, something we at iFSN are beginning to explore in a more structured manner (really, I’m getting’ some culture from Amy the French professor and outdoor survivalist).

Prince’s slow Southern drawl stands out from the languages spoken by customers who have found their way to Central Indiana from Morocco, Yemen, Nigeria, Kenya, Pakistan, Mexico and other places around the globe where goat is a dietary staple.

For some, butchering their own meat helps maintain a link to cultures they’ve left behind in Africa, Central America and the Middle East. Others, including the large number of Muslims who buy from Prince, prefer to kill and butcher the animals themselves to ensure food preparation standards of their faith are followed.

Prince said he doesn’t know a lot about Islam, but he is savvy enough as a businessman to make sure the slaughterhouse meets their needs — including situating the killing table so it faces east toward Mecca.

Goats, like all ruminants, are natural reservoirs for E. coli O157:H7. So be clean, be safe, unlike the employees of the Captains Galley’s restaurant in China Grove, N.C., who earlier this year slaughtered a goat after hours, leading to an O157 outbreak that sickened 21 and killed an 86-year-old. Safety and culture can go together.

.jpg) Yes, imported foods can be problematic. But so can homegrown foods. The silence surrounding California lettuce as a possible source of E. coli O157:H7 outbreaks in Michigan and Ontario is beyond disturbing. And the more fingers are pointed to imports, the fewer questions are asked about domestic supplies.

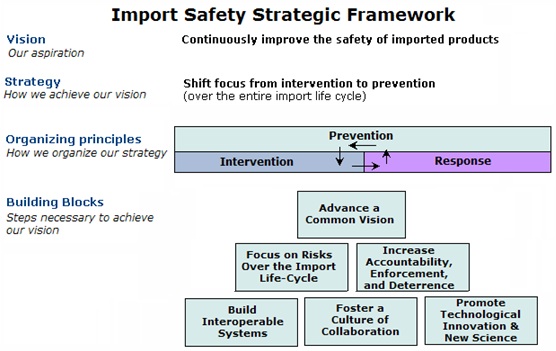

Yes, imported foods can be problematic. But so can homegrown foods. The silence surrounding California lettuce as a possible source of E. coli O157:H7 outbreaks in Michigan and Ontario is beyond disturbing. And the more fingers are pointed to imports, the fewer questions are asked about domestic supplies.

“The goal is to radically redesign the process,” said Dr. David Acheson (right, exactly as shown), the agency’s associate commissioner for foods. For imported food, for instance, that means trying to detect tainted products during the production process rather than waiting until they enter the country.

“The goal is to radically redesign the process,” said Dr. David Acheson (right, exactly as shown), the agency’s associate commissioner for foods. For imported food, for instance, that means trying to detect tainted products during the production process rather than waiting until they enter the country. After seeing some food-safety problems at Fiesta Time, a new Mexican restaurant in Clintonville, a city inspector realized he was facing a language barrier, came back to the office and talked to co-worker Vince Fasone.

After seeing some food-safety problems at Fiesta Time, a new Mexican restaurant in Clintonville, a city inspector realized he was facing a language barrier, came back to the office and talked to co-worker Vince Fasone. The

The  No.

No. .jpg) I expressed a similar notion this morning in the

I expressed a similar notion this morning in the  the key to growing is to be an eager learner. One cutting-edge difference in the best leaders I’ve been around is that they truly are avid learners."

the key to growing is to be an eager learner. One cutting-edge difference in the best leaders I’ve been around is that they truly are avid learners." Amy has survival skills. She knows how to field-dress animals. And has pretty good bowstaff skills.

Amy has survival skills. She knows how to field-dress animals. And has pretty good bowstaff skills.

Spent yesterday driving to Oklahoma City and back to speak at the

Spent yesterday driving to Oklahoma City and back to speak at the