On Aug. 23, 2008, Maple Leaf CEO Michael McCain took to the Intertubes to apologize for an expanding outbreak of listeriosis that would eventually kill 22 people. As part of his speech, McCain said that Maple Leaf has “a strong culture of food safety.”

.jpg) On Aug. 27, 2008, McCain told a press conference,

On Aug. 27, 2008, McCain told a press conference,

“As I’ve said before, Maple Leaf Foods is 23,000 people who live in a culture of food safety. We have an unwavering commitment to keep our food safe, and we have excellent systems and processes in place.”

As laid bare in the Weatherill report on the 2008 listeria shit-fest, McCain’s invocation of food safety culture was as credible as the politicians and bureaucrats who lauded the workings of Canada’s food safety surveillance system, when it didn’t actually work at all.

“the root of the listeriosis outbreak in Canada in 2008 was not two dirty meat slicers but rather a culture – in government and private enterprise alike – in which food safety was not a priority but an afterthought.”

Picard says Ms. Weatherill’s most important recommendation – one that has been largely glossed over in media coverage of the report – is for a culture of safety or, as is stated bluntly in the report: “Actions, not words.”

Really, Canada, this is nothing new. There is a long history in developed countries of negligence, followed by remorse, promises to do better and … minimal changes. Didn’t Canada go through all this after E. coli O157:H7 entered the municipal water supply in Walkerton, Ontario in 2000, killing 7 and sickening 2,500 in a town of 5,000?

In 1985, 19 of 55 affected people at a London, Ontario, nursing home died after eating sandwiches infected with E. coli O157:H7. On Oct. 12, 1985, in response to an inquest, the Ontario government announced a training program for food-handlers in health-care institutions, “stressing cleaning and sanitizing procedures and hygienic practices in food preparation.” That training apparently didn’t include the food safety basic – don’t give unheated cold cuts to vulnerable populations, like old people, ‘cause they may die from listeria.

These days, food safety culture is the buzz. The same recommendation – to embrace and enhance food safety culture — was embraced by the U.K. Food Standards Agency last week following an inquiry into the death of 5-year-old Mason Jones and the illness of 160 other schoolchildren who consumed E. coli O157:H7 contaminated cold cuts in Wales in 2005.

These days, food safety culture is the buzz. The same recommendation – to embrace and enhance food safety culture — was embraced by the U.K. Food Standards Agency last week following an inquiry into the death of 5-year-old Mason Jones and the illness of 160 other schoolchildren who consumed E. coli O157:H7 contaminated cold cuts in Wales in 2005.

Sixteen years after E. coli O157:H7 killed four and sickened hundreds who ate hamburgers at the Jack-in-the-Box chain, the challenge remains: how to get people to take food safety seriously? ??????Lots of companies do take food safety seriously and the bulk of Western meals are microbiologically safe. But recent food safety failures have been so extravagant, so insidious and so continual that consumers must feel betrayed.??????

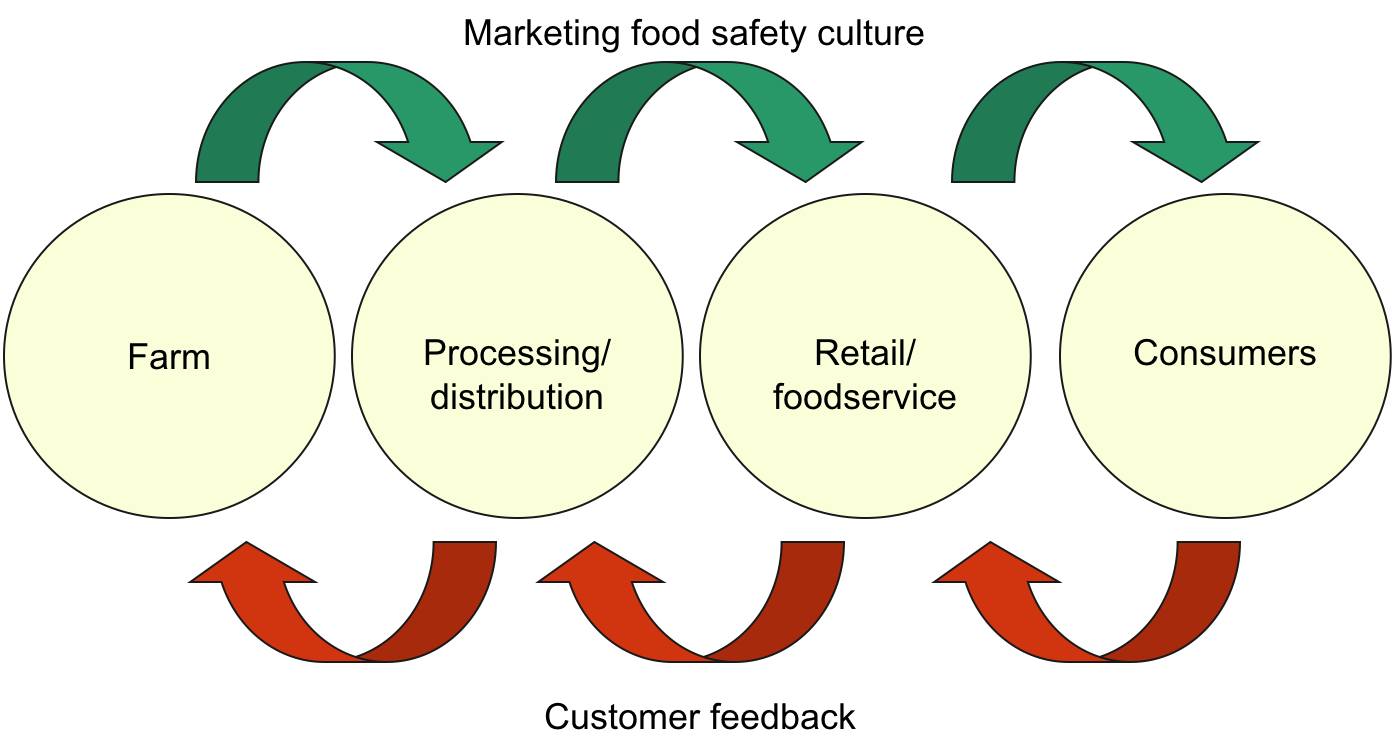

Culture encompasses the shared values, mores, customary practices, inherited traditions, and prevailing habits of communities. The culture of today’s food system (including its farms, food processing facilities, domestic and international distribution channels, retail outlets, restaurants, and domestic kitchens) is saturated with information but short on behavioral-change insights. Creating a culture of food safety requires application of the best science with the best management and communication systems, including compelling, rapid, relevant, reliable and repeated, multi-linguistic and culturally-sensitive messages.

Frank Yiannas, the vice-president of food safety at Wal-Mart writes in his 2008 book, Food Safety Culture: Creating a Behavior-based Food Safety Management System, that an organization’s food safety systems need to be an integral part of its culture.

The other guru of food safety culture, Chris Griffith of the University of Wales, features prominently in the report by Professor Hugh Pennington into the 2005 E.coli outbreak in Wales.

I’ve maintained for 16 years that, despite high-profile outbreaks and unacceptable loss of life, food safety in Canada is, as Weatherill stated, an afterthought.

Forget government. Michael McCain, you want to be a leader, lead, don’t just talk about it by throwing around words like food safety culture because they are suddenly fashionable.

The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

The best food producers, processors, retailers and restaurants will go above and beyond minimal government and auditor standards and sell food safety solutions directly to the public. The best organizations will use their own people to demand ingredients from the best suppliers; use a mixture of encouragement and enforcement to foster a food safety culture; and use technology to be transparent — whether it’s live webcams in the facility or real-time test results on the website — to help restore the shattered trust with the buying public.

And the best cold-cut companies may stop dancing around and tell pregnant women, old people and other immunocompromised folks, don’t eat this food unless it’s heated.

Weatherill says, action not words.

.jpg) So she did.

So she did.  He said medium-well.

He said medium-well. Y

Y.jpeg)

The intersections of food safety, language and culture are ripe for study. And action. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, yesterday launched a

The intersections of food safety, language and culture are ripe for study. And action. The U.S. Department of Agriculture, yesterday launched a

.jpg) “While most successful food producers are far more diligent — big name-brand peanut butter is considered safe, for example — American consumers have faced far too many food-supply emergencies in the last few years.”

“While most successful food producers are far more diligent — big name-brand peanut butter is considered safe, for example — American consumers have faced far too many food-supply emergencies in the last few years.”(1)(1).jpg) “President Obama promised during the campaign to create a government that does a better job of protecting the American consumer. The nation’s vulnerable food supply is a healthy place to start.”

“President Obama promised during the campaign to create a government that does a better job of protecting the American consumer. The nation’s vulnerable food supply is a healthy place to start.”(1).jpg) In 1204 in Montpellier, France, a butcher selling a substitute meat in place of the advertized beast was required by statute to reimburse the customer twice the amount paid. In Narbonne, regulations dictated a whipping “with sheep tripe” in front of the food stall for unscrupulous sellers. China routinely executes its biggest food frauds.

In 1204 in Montpellier, France, a butcher selling a substitute meat in place of the advertized beast was required by statute to reimburse the customer twice the amount paid. In Narbonne, regulations dictated a whipping “with sheep tripe” in front of the food stall for unscrupulous sellers. China routinely executes its biggest food frauds..jpg) Even Whole Foods, where consumers pay a hefty premium for basic foodstuffs, said the company carefully checks the paperwork for all the products it sells, but can do no better than the minimal standard of government. “For the thousands of products we sell, that’s the extent we can go to. The rest of it is up to the F.D.A. and to the manufacturer.”

Even Whole Foods, where consumers pay a hefty premium for basic foodstuffs, said the company carefully checks the paperwork for all the products it sells, but can do no better than the minimal standard of government. “For the thousands of products we sell, that’s the extent we can go to. The rest of it is up to the F.D.A. and to the manufacturer.”

.png) As reported by the

As reported by the  crumbling across the nation,” and it’s leading consumers to “tak[e] a healthy interest in vegetables and other locally made produce.”

crumbling across the nation,” and it’s leading consumers to “tak[e] a healthy interest in vegetables and other locally made produce.”