William Neuman of the New York Times writes this morning that for the first time in the U.S., public health officials have linked ground beef to illnesses from a rare strain of E. coli, adding fuel to an already fierce debate over expanding federal rules meant to keep the toxic bacteria out of the meat .jpg) supply.

supply.

Cargill Meat Solutions recalled 8,500 pounds of hamburger on Saturday after investigators determined that it was the likely source of a bacterial strain known as E. coli O26, which had sickened three people in Maine and New York.

Under federal rules, it is illegal to sell ground beef containing a more common strain of the bacteria, E. coli O157:H7, which has been responsible for thousands of illnesses, many deaths and the recall of millions of pounds of beef over the years. But federal regulators are now considering whether to give the same illegal status to at least six other E. coli strains, including O26, which can also make people violently sick.

The meat industry has opposed such a change, saying it is not needed. Among the arguments the industry has used was one stubborn fact: no outbreak in this country from the rarer strains of E. coli had ever been definitively tied to ground beef.

James Marsden, a professor of food safety and security at Kansas State University, said about the outbreak and recall,

“It might act as a catalyst. Clearly it’s back on the front burner, that’s for sure, and clearly USDA is under pressure.”

The federal Agriculture Department has been trying for several years to decide what to do about the additional strains of E. coli. The issue now falls in the lap of the Obama administration’s new head of food safety at the department, Dr. Elisabeth Hagen, who was appointed last month.

Dr. Hagen has yet to say publicly what she plans to do. But in a written statement provided to The New York Times, she said, “In order to best prevent illnesses and deaths from dangerous E. coli in beef, our policies need to evolve to address a broader range of these pathogens, beyond E.coli O157:H7. … Our approach should ensure that public health and food safety policy keeps pace with the demonstrated advances in science and data about foodborne illness to best protect consumers.”

The agency has said that it is reluctant to make additional forms of toxic E. coli illegal in ground beef until it has developed a rapid test that can detect those strains in packing plants. Such tests are not expected to be ready until at least late next year.

The beef industry argued against declaring the additional E. coli strains illegal in an Aug. 18 letter that the American Meat Institute, a trade group, sent to the agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack.

The beef industry argued against declaring the additional E. coli strains illegal in an Aug. 18 letter that the American Meat Institute, a trade group, sent to the agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack.

Giving the strains illegal status could “cause more harm than good,” the letter said, by forcing costly testing when resources would be better spent on measures to prevent bacteria from getting into the meat in the first place.

It said that measures the industry had taken to combat the most common strain of E. coli were also effective against the other strains, and it urged the agency to conduct further studies before making a decision.

James H. Hodges, the meat institute’s executive vice president, said that a single outbreak did not alter the industry’s position.

“We have never said it wasn’t a potential public health problem. The debate is what’s the appropriate regulatory program.”

And once again, J. Patrick Boyle, president of the American Meat Institute, going mano-a-mano with Stephen Colbert on issues like non-O157 STECs.

other label information, provides open and transparent information based on recognizable common and usual product names and should be kept,” the comments say.

other label information, provides open and transparent information based on recognizable common and usual product names and should be kept,” the comments say.

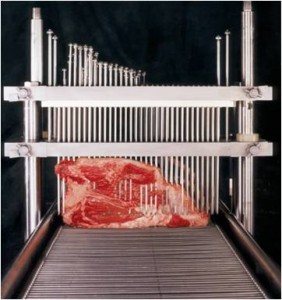

meat glue, where cheap cuts of meat were allegedly glued together and shaped to look like a fillet mignon.

meat glue, where cheap cuts of meat were allegedly glued together and shaped to look like a fillet mignon..jpg)

.jpg) could have been prevented" if the proposed "test and hold" rule it is unveiling Tuesday had been in place.

could have been prevented" if the proposed "test and hold" rule it is unveiling Tuesday had been in place..jpg) supply.

supply. The beef industry argued against declaring the additional E. coli strains illegal in an Aug. 18 letter that the American Meat Institute, a trade group, sent to the agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack.

The beef industry argued against declaring the additional E. coli strains illegal in an Aug. 18 letter that the American Meat Institute, a trade group, sent to the agriculture secretary, Tom Vilsack. Florida.

Florida.