An edited version of this fascinating Times story is below:

“This is the spot,” said Morris Njeru, gazing down at a tangled patch of farmland where he recently found the bloody corpses of David, Mukurino and Scratch — his last donkeys.

Mr. Njeru, 44, a market porter who depends on his animals to ferry goods around this city, had already lost five donkeys earlier in the year. In each case, the thieves slit the animals’ throats and skinned them from the neck down, leaving the meat to vultures and hyenas.

Mr. Njeru, 44, a market porter who depends on his animals to ferry goods around this city, had already lost five donkeys earlier in the year. In each case, the thieves slit the animals’ throats and skinned them from the neck down, leaving the meat to vultures and hyenas.

Four months later, all Mr. Njeru could find of the animals was a single hoof, which he pocketed as a memento.

Rachel Nuwer of the New York Times writes there are scant remains, too, of Mr. Njeru’s once comfortable life. Without his animals, his income plummeted from nearly $30 per day to less than $5. He can no longer afford payments on a loan for a small piece of property he rented, and he fears he will have to take his child from boarding school.

“My life has completely changed,” he said. “I was depending on these donkeys to feed my family.”

For Mr. Njeru and millions of others around the world, donkeys are the primary means to transport food, water, firewood, goods and people. In China, however, they have another purpose: the production of ejiao, a traditional medicine made from gelatin extracted from boiled donkey hides.

Ejiao was once prescribed primarily to supplement lost blood and balance yin and yang, but today it is sought for a range of ills, from delaying aging and increasing libido to treating side effects of chemotherapy and preventing infertility, miscarriage and menstrual irregularity in women.

While ejiao has been around for centuries, its modern popularity began to grow around 2010, when companies such as Dong-E-E-Jiao — the largest manufacturer in China — launched aggressive advertising campaigns. Fifteen years ago, ejiao sold for $9 per pound in China; now, it fetches around $400 per pound.

As demand increased, China’s donkey population — once the world’s largest — has fallen to fewer than six million from 11 million, and by some estimates possibly to as few as three million. Attempts to replenish the herds have proved challenging: Unlike cows or pigs, donkeys do not lend themselves to intensive breeding. Females produce just one foal per year and are prone to spontaneous abortions under stressful conditions.

So Chinese companies have begun buying donkey skins from developing nations. Out of a global population of 44 million, around 1.8 million donkeys are slaughtered per year to produce ejiao, according to a report published last year by the Donkey Sanctuary, a nonprofit based in the United Kingdom.

So Chinese companies have begun buying donkey skins from developing nations. Out of a global population of 44 million, around 1.8 million donkeys are slaughtered per year to produce ejiao, according to a report published last year by the Donkey Sanctuary, a nonprofit based in the United Kingdom.

“There’s a huge appetite for ejiao in China that shows no signs of diminishing,” said Simon Pope, manager of rapid response and campaigns for the organization. “As a result, donkeys are being Hoovered out of communities that depend on them.”

In November, researchers at the Beijing Forestry University warned that China’s demand for ejiao may cause donkeys “to become the next pangolin.”

“In 2016, this business of donkeys erupted,” said Obassy Nguvillah, a police superintendent in Tanzania’s Monduli district, near the Kenyan border. “There were increasing numbers of cases of guys passing into the Maasai area, taking people’s donkeys and transporting them to the Chinese-owned processing plant.”

In Esilalei — a village located on a sprawling, drought-plagued savanna under Mr. Nguvillah’s watch — residents lost nearly 475 donkeys in a single year. While about 175 of the animals were recovered by tracking the thieves into the bush, police believe the remainder were sold to slaughterhouses. Unable to afford replacements, the former owners are still reeling.

Unlike Tanzania, Kenya’s donkey skin trade shows no signs of slowing. In 2016, prices for skins were fifty times higher than in 2014, while prices for live donkeys have nearly tripled, from about $60 to $165.

The country’s three abattoirs — all of which have Chinese owners or partners — reported processing just under 100,000 donkeys in two years, according to a government memo. Both skin and meat are exported to China, usually through Vietnam or Hong Kong.

Seventeen skin traders have also opened shop, mostly in Nairobi, and a fourth abattoir is rumored to be on the way. The abattoir owners insist that they are bettering the country by generating jobs and paying handsome prices for unneeded donkeys.

“This business has helped so many people,” said John Kariuki, director of Star Brilliant Donkey Export Abattoir in Naivasha. “Instead of having to sell cows and goats, Maasai pastoralists are selling donkeys to pay their children’s school fees.”

Goldox Donkey Slaughterhouse in Baringo County — the largest of Kenya’s abattoirs, claiming to process some 450 donkeys a day — also attempts to spread good will by providing free water to neighbors, and by paying school fees for four local children.

Waste disposal has become a significant issue. Last fall, Goldox began dumping donkey remains at a parcel of land it purchased in Chemogoch village, down the road from its slaughterhouse.

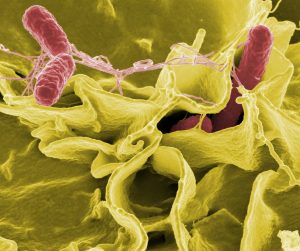

After residents living adjacent to the site complained, the company began burying the waste rather than leaving it in the open. But neighbors say the situation is still unacceptable, accusing the company of contaminating ground water and breeding disease.

“Should we go into the cocaine business or the sale of elephant tusks just because it makes money?” asked Dr. Onyango

After these 2 new victims, 6 cases of human brucellosis have been

After these 2 new victims, 6 cases of human brucellosis have been

But my carnivorous mantra doesn’t match the advice of Michael Pollan, author of In Defense of Food—An Eaters Manifesto (right). He says:

But my carnivorous mantra doesn’t match the advice of Michael Pollan, author of In Defense of Food—An Eaters Manifesto (right). He says: