I got invited by one of my former students to give a talk about food safety stuff at an American military base in Germany, about 2012.

This was after 5,500 people became sick and 53 died from E. coli O104 linked to raw sprouts, primarily in Germany.

This was after 5,500 people became sick and 53 died from E. coli O104 linked to raw sprouts, primarily in Germany.

Met a couple of lifelong friends, continued my work with the U.S. military, because those folks need to eat too, and learned that public bathroom in Germany is an oxymoron and people just piss at the side of the road (Australia has excellent public bathrooms, best I’ve ever seen).

After my presentation, one of my military friends said, guess you’re not a fan of Jimmy John’s.

I said, no, I’m not a fan of bullshit.

Before the U.S. government shut down, the folks at the Centers for Disease Control managed to publish the latest outbreak info of Salmonella linked to raw sprouts in Jimmy Johns subs, the preferred lunch meeting snack for Kansas State University food professors, who know nothing about safety.

To recap:

An outbreak linked to raw sprouts in the U.S. that sickened 140 people occurred between November 2010 into 2011, involving sandwich franchise, Jimmy John’s (CDC, 2011; Illinois Department of Public Health, 2010).

The owner of the Montana Jimmy John’s outlet, Dan Stevens, expressed confidence in his sprouts claiming that because the sprouts were locally grown they would not be contaminated, although the source of the contaminated sprouts had not yet been identified (KRTV, 2010).

By the end of December 2010 a sprout supplier, Tiny Greens Farm, was implicated in the outbreak (Food and Drug Administration, 2010).

Jimmy John’s owner, John Liautaud, responded by stating the sandwich chain would replace alfalfa sprouts with clover sprouts since they were allegedly easier to clean (Associated Press, 2011c). However, a week earlier a separate outbreak had been identified in Washington and Oregon (still miss ya, Bill Keene) in which eight people were infected with Salmonella after eating sandwiches containing clover sprouts from a Jimmy John’s restaurant (Oregon Department of Human Services, 2011; Terry, 2011). This retailer was apparently not aware of the risks associated with sprouts, or even outbreaks associated with his franchisees.

The FDA inspection of the Tiny Greens facility found numerous issues which may have led to pathogen contamination, including “the company grew sprouts in soil from the organic material decomposed outside without using any monitored kill step on it,” mold was found in the mung-bean sprouting room, and the antimicrobial treatment for seeds was not demonstrated to be equivalent to the recommended FDA treatment (Roos, 2011).

Months later, Bill Bagby Jr, owner of Tiny Greens, was quoted as saying “after the changes we made, it’s next to impossible for anything to happen,” hindering communication efforts by being defensive and overconfident (Des Garennes, 2011; Sandman & Lanard, 2011). Bagby also expressed confidence in sprouts following the German outbreak, commenting that for many like him, the nutritional benefits outweigh the risk: “Sprouts are kind of a magical thing. That’s why I would advise people to only buy sprouts from someone who has a (food safety) program in place (that includes outside auditors). We did not have (independent auditors) for about one year, and that was the time the problems happened. The FDA determined that unsanitary conditions could have been a potential source of cross-contamination and so we have made a lot of changes since then.”

In the second week of October, 2013, three Jimmy John’s restaurants in the Denver Metro area reportedly served up sandwiches that sickened eight people with E. coli bacteria.

In the second week of October, 2013, three Jimmy John’s restaurants in the Denver Metro area reportedly served up sandwiches that sickened eight people with E. coli bacteria.

“We believe that their illness came from a produce item that was on those sandwiches that they ate,” said Alicia Cronquit, epidemiologist with the Colorado Department of Public Health and Environment.

Cronquist said all eight cases were reported between October 18th and 22nd, and all of the people impacted ate at Jimmy John’s between October 7th and 15th.

The Department of Public Health has not closed down the three restaurants, and will not identify their locations because Cronquist says they do not believe the restaurants are at fault.

“Our leading hypothesis for what’s happened is that there was a contaminated produce item that was distributed to the stores,” Cronquist said. “We have not identified any food handling issues at the particular establishments that we think would contribute to illness.”

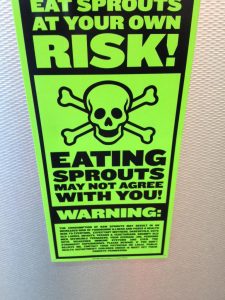

Raw sprouts are the poster child for failures in what academics call risk communication.

About 1999, graduate student Sylvanus Thompson started working with me on risk analysis associated with sprouts. He got his degree and went on to rock-star status in the food safety world with the implementation of the red-yellow-green restaurant inspection disclosure program with Toronto Public Health, but we never published anything.

I remember frantically flying to Kansas City to hang out with this girl in Manhattan (Kansas) I’d met a couple of weeks before, in the midst of the 2005 Ontario raw sprout outbreak that sickened over 700; Jen Tryon, now with Global News, interviewed me at the airport, with me wearing a K-State hockey shirt (that’s the joke; there is no hockey at K-State, and I was still employed by Guelph; and I was going to hang out with this girl).

After the German E. coli O104 outbreak, along with the ridiculous public statements and blatant disregard for public safety taken by sandwich artist Jimmy John’s in the U.S., I figured we really needed to publish something.

The basic conclusions:

- raw sprouts are a well-documented source of foodborne illness;

- risk communication about raw sprouts has been inconsistent; and,

- continued outbreaks question effectiveness of risk management strategies and producer compliance.

We document at least 55 sprout-associated outbreaks occurring worldwide affecting a total of 15,233 people since 1988. A comprehensive table of sprout-related outbreaks can be found here.

Sprouts present a unique food safety challenge compared to other fresh produce, as the sprouting process provides optimal conditions for the growth and proliferation of pathogenic bacteria. The sprout industry, regulatory agencies, and the academic community have been collaborating to improve the microbiological safety of raw sprouts, including the implementation of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), establishing guidelines for safe sprout production, and chemical disinfection of seed prior to sprouting. However, guidelines and best practices are only as good as their implementation. The consumption of raw sprouts is considered high-risk, especially for young, elderly and immuno-compromised persons (FDA, 2009).

Sprouts present a unique food safety challenge compared to other fresh produce, as the sprouting process provides optimal conditions for the growth and proliferation of pathogenic bacteria. The sprout industry, regulatory agencies, and the academic community have been collaborating to improve the microbiological safety of raw sprouts, including the implementation of Good Manufacturing Practices (GMP), establishing guidelines for safe sprout production, and chemical disinfection of seed prior to sprouting. However, guidelines and best practices are only as good as their implementation. The consumption of raw sprouts is considered high-risk, especially for young, elderly and immuno-compromised persons (FDA, 2009).

In late December 2011, less than one year after making the switch to clover sprouts, Jimmy John’s was linked to another sprout related outbreak, this time it was E.coli O26 in clover sprouts. In February 2012, sandwich franchise Jimmy John’s announced they were permanently removing raw clover sprouts from their menus. As of April 2012, the outbreak had affected 29 people across 11 states. Founder and chief executive, John Liautaud, attempted to appease upset customers through Facebook stating, “a lot of folks dig my sprouts, but I will only serve the best of the best. Sprouts were inconsistent and inconsistency does not equal the best.” He also informed them the franchise was testing snow pea shoots in a Campaign, Illinois store, although there is no mention regarding the “consistency” or safety of this choice.

In spite of widespread media coverage of sprout-related outbreaks, improved production guidelines, and public health enforcement actions, awareness of risk remains low. Producers, food service and government agencies need to provide consistent, evidence-based messages and, more importantly, actions. Information regarding sprout-related risks and food safety concerns should be available and accurately presented to producers, retailers and consumers in a manner that relies on scientific data and clear communications.’

On Friday, Jan. 19, 2018, CDC along with public health and regulatory officials in several states, and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced a multistate outbreak of Salmonella Montevideo infections that has sickened at least eight people.

Illnesses started on dates ranging from December 20, 2017 to January 3, 2018. Ill people range in age from 26 to 50, with a median age of 34. All 8 (100%) are female. No hospitalizations and no deaths have been reported.

Epidemiologic evidence indicates that raw sprouts served at Jimmy John’s restaurants are a likely source of this multistate outbreak.

In interviews, ill people answered questions about the foods they ate and other exposures in the week before they became ill. Seven (88%) of eight people interviewed reported eating at multiple Jimmy John’s restaurant locations. Of these seven people, all seven (100%) reported eating raw sprouts on a sandwich from Jimmy John’s in Illinois and Wisconsin. This proportion is significantly higher than results from a survey[PDF – 29 pages] of healthy people, in which 3% reported eating sprouts on a sandwich in the week before they were interviewed. Two ill people in Wisconsin ate at a single Jimmy John’s location in that state.

Federal, state, and local health and regulatory officials are conducting traceback investigations from the six Jimmy John’s locations where ill people ate raw sprouts. These investigations are ongoing to determine where the sprouts were distributed, and to learn more about the potential route of contamination.

Federal, state, and local health and regulatory officials are conducting traceback investigations from the six Jimmy John’s locations where ill people ate raw sprouts. These investigations are ongoing to determine where the sprouts were distributed, and to learn more about the potential route of contamination.

The information available to date indicates that raw sprouts served at Jimmy John’s restaurants in Illinois and Wisconsin may be contaminated with Salmonella Montevideo and are not safe to eat. CDC recommends that consumers not eat raw sprouts served at Jimmy John’s restaurants in Illinois and Wisconsin.

Failures in sprouts-related risk communication

Food Control.2012. 10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.08.022

Erdozain, M.S., Allen, K.J., Morley, K.A. and Powell, D.A.

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956713512004707?v=s5

Nutritional and perceived health benefits have contributed to the increasing popularity of raw sprouted seed products. In the past two decades, sprouted seeds have been a recurring food safety concern, with at least 55 documented foodborne outbreaks affecting more than 15,000 people. A compilation of selected publications was used to yield an analysis of the evolving safety and risk communication related to raw sprouts, including microbiological safety, efforts to improve production practices, and effectiveness of communication prior to, during, and after sprout-related outbreaks. Scientific investigation and media coverage of sprout-related outbreaks has led to improved production guidelines and public health enforcement actions, yet continued outbreaks call into question the effectiveness of risk management strategies and producer compliance. Raw sprouts remain a high-risk product and avoidance or thorough cooking are the only ways that consumers can reduce risk; even thorough cooking messages fail to acknowledge the risk of cross-contamination. Risk communication messages have been inconsistent over time with Canadian and U.S. governments finally aligning their messages in the past five years, telling consumers to avoid sprouts. Yet consumer and industry awareness of risk remains low. To minimize health risks linked to the consumption of sprout products, local and national public health agencies, restaurants, retailers and producers need validated, consistent and repeated risk messaging through a variety of sources.