On Sunday, May 21, 2000, at 1:30 p.m., the Bruce Grey Owen Sound Health Unit in Ontario, Canada, posted a notice to hospitals and physicians on their web site to make them aware of a boil water advisory and that a suspected agent in the increase of diarrheal cases was E. coli O157:H7.

There had been a marked increase in illness in the town of about 5,000 people, and many were already saying the water was suspect. But the first public announcement was also the Sunday of the Victoria Day long weekend and received scant media coverage.

There had been a marked increase in illness in the town of about 5,000 people, and many were already saying the water was suspect. But the first public announcement was also the Sunday of the Victoria Day long weekend and received scant media coverage.

It wasn’t until Monday evening that local television and radio began reporting illnesses, stating that at least 300 people in Walkerton were ill.

At 11:00 a.m., on Tuesday May 23, the Walkerton hospital jointly held a media conference with the health unit to inform the public of outbreak, make the public aware of the potential complications of the E. coli O157:H7 infection, and to tell the public to take the necessary precautions. This generated a print report in the local paper the next day, which was picked up by the national wire service Tuesday evening, and subsequently appeared in papers across Canada on May 24.

Ultimately, 2,300 people in a town of 5,000 were sickened and seven died. All the gory details and mistakes and steps for improvement were outlined in the report of the Walkerton inquiry.

Paul Hunter of the Toronto Star writes it was a glorious, sun-warmed afternoon after a long winter. Robbie Schnurr’s blinds were closed. He was finalizing his plans to die.

“Pretty much where I’m laying right now, where I’ve been for years,” he said, reflexively patting the bedsheet between him and the half-finished bottles of water kept within easy reach.

“What does a person do when they know they’re going to die within hours? I mean, do you walk over and look out the window? I can’t walk anyways. I guess you just wait for the time to pass and then you miss the hors d’oeuvres.”

It’s been 18 years since a deadly E. coli outbreak devastated the rural town of Walkerton, 150 kilometres northwest of Toronto. Seven people perished. A further 2,500, half the population, took ill. Most eventually got better. Schnurr never did.

Poisoned like the others, his health declined slowly and painfully until he lived in a sort of limbo: a prisoner in his own body, in his own bed, here in his 11th-floor Mississauga condo, a 71-year-old alone and feeling largely forgotten.

The former OPP officer and investigator with Ontario’s Office of the Fire Marshal was in constant pain from a degenerative nerve disease. Doctors, he said, told him he would continue to decline. There was no hope of improvement.

The former OPP officer and investigator with Ontario’s Office of the Fire Marshal was in constant pain from a degenerative nerve disease. Doctors, he said, told him he would continue to decline. There was no hope of improvement.

His legs had wasted away. Numbness in his fingers made it impossible for him to write or button a shirt; he opened bottles of painkillers with his mouth. He was losing sight in his right eye; the hearing in one ear was already gone. He’d leave his home only every two weeks, strapped on a gurney to be transported to the Queensway Health Centre for an intravenous immunoglobulin treatment. He went for the last time in late April.

On May 1, a doctor came to him.

In the company of his younger sister, Barbara Ribey, her husband, Norm, and two friends, Schnurr fulfilled his wish for a physician-assisted death.

“I just won’t live like this anymore,” he explained the day before that final moment. “There’s nothing to look forward to, there’s no goals in life. There’s nothing.”

Before he took ill, Schnurr said he “had the world by the ass.” He wanted people to know that. He also didn’t want forgotten what happened at Walkerton and how it cheated him, and others from his hometown, in life and left a heartbreaking legacy.

Schnurr said he also recently spoke to two old friends from the OPP who’d had no idea of what became of him.

He wanted everyone to know. So he invited the Star to his home to share his story and explain his decision.

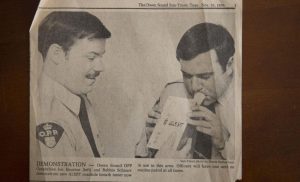

Schnurr was, as it would have been described in another era, a man’s man, living like he was the lead in a 1970s action movie.

Mustachioed and handsome, he drove fast cars (the last a black Corvette), lived for long stretches on his 35-foot boat (where the parties were frequent) and had a closet full of Armani and Hugo Boss suits and silk ties. He owned a condo in Mexico and, befitting a Hollywood star, he always seemed to have a beautiful date on his arm.

“Women loved Robbie,” said Ribey.

Schnurr skied, he rollerbladed, he had a black belt in karate. As a teen, he played every sport he could. He excelled at hockey and was never afraid to drop the gloves. In baseball, a fastball in the low to mid-90s caught a scout’s eye, and he went off to pitch in the minors in North Carolina.

“I know I could have made the big leagues, but I didn’t know how long it would take,” he said. “And there was this girl that wanted me to get married. When I got home she handed me an application for the OPP.”

The policing job idea stuck, but the thought of marriage didn’t. Schnurr became a cadet at 19, was sworn in and got his gun at 21. He said he was shot twice and stabbed twice. He lost hearing in one ear because of target shooting practice. He investigated motorcycle gangs — “We didn’t get along real well, the bikers and I” — and major crimes.

He moved from Owen Sound to Kenora to Manaki before landing in Orillia in the early 1980s shortly before a train derailed in nearby Medonte. The fire marshal’s office was impressed with how he handled that case and suggested he apply. Schnurr said he beat out 800 other candidates for the job and was soon sent off to train with the FBI to become an expert in explosions.

In newspapers during the ’80s and ’90s, Schnurr was frequently quoted standing among the ashes at one fire or another. He figured he investigated some 2,000 fires. At one point, he helped profile and hunt down an arsonist who was terrorizing Toronto’s west end. On another case, the torching of a church, he received death threats.

Through his working life, sports remained important, as he coached youth baseball and organized instructional clinics around the province.

Through his working life, sports remained important, as he coached youth baseball and organized instructional clinics around the province.

Though single at the end, he had married twice, had a daughter, Samantha, whom he adored and a grandson, Kaiden, born in January.

Tough as he was, through a twist of fate Schnurr was exiled from the world he embraced so enthusiastically.

“Now, I can’t even get down the goddamned hall,” he said. “To make a long story short, I was screwed.”

Schnurr didn’t even live in Walkerton when he encountered his kryptonite there. He’d gone to his hometown for his mother’s memorial in mid-May of 2000. When he returned to Mississauga, he realized he’d forgotten his suit jacket. With Victoria Day weekend coming, he decided to make a quick return trip to Walkerton to pick it up and see a couple of friends on the Friday before the holiday traffic got heavy.

“It was a really hot and muggy day and when I got there, I took a pitcher of water and chugalugged it,” he said.

That began a weekend of hell that lasted 18 years.

“I had blood coming out of both ends,” he said of the next 48 hours, spent feeling groggy and on the floor of his condo. “It was almost two days before I could get any help because I wasn’t strong enough.”

Walkerton’s water supply had been contaminated. A heavy rainstorm washed cow manure carrying a strain of E. coli O157:H7 into a vulnerable town well and, because of improper chlorination, the lethal bacteria was not destroyed.

The poison was passed on through tainted tap water and made thousands sick with severe gastrointestinal issues, including bloody diarrhea, in one of the worst public health disasters in Canadian history. A landmark, seven-year study of those who fell ill, released in 2008, determined there were legacy illnesses from the tragedy. Patients who had confirmed gastroenteritis had a 30 per cent higher risk of high blood pressure or kidney damage.

The study found that 22 children who became sick in 2000 had permanent kidney damage, but treatment had stopped that illness from getting worse.

Dr. William Clark, a kidney specialist at London Health Sciences Centre who led the study, looked again three years ago at the victims of Walkerton, and found that although “there is no doubt some people have had significant long-term problems” when compared with similar small towns, Walkerton is actually doing “somewhat better” when it comes to kidney and heart issues.

That, he suggests, could be related to a post-crisis medical screening program involving about 4,000 residents. It not only identified health issues related to the contamination, but also picked up ailments such as diabetes and hypertension, allowing physicians to get those patients on proper medication.

Clark said the kidney and heart issues of Walkerton residents have improved, but “there’s no doubt they’re on more medication” than comparable groups.

Schnurr had no idea others were also poisoned as he floundered on his condominium floor in 2000. He didn’t know why he was sick, even as an ambulance eventually took him, in blood-soaked clothes, to the hospital. He also wondered why all the medical staff took such keen interest in his Walkerton roots. Then, on one of the muted televisions at the hospital, he started to see familiar faces from his hometown.

“I’m going, ‘What’s going on?’ (A hospital worker) said to me, ‘You haven’t heard about the E. coli epidemic in Walkerton?’ Bang. It all came together.”

Schnurr returned to work until 2002, but he got progressively weaker. His retirement plan had been to take a lucrative position investigating insurance fraud in the U.S., or set up his own business. Instead, he struggled with balance, falling often, and forgot things. At 55, he could no longer work.

Schnurr said the bacterial infection destroyed his immune system and that led to his current neurological disorder. Press reports, years after the Walkerton disaster, chronicled Schnurr’s struggles as a lingering victim.

Doctors eventually diagnosed Schnurr with chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyneuropathy (CIDP), a neurological disorder that causes the body’s immune system to attack and destroy the myelin sheath that envelops nerves. It’s comparable to stripping the insulation off electrical wires. Symptoms include tingling in the feet and hands as well as progressive weakness in the legs and arms. For Schnurr, it also brought debilitating pain.

“Anything too hot or too cold on him would almost be like tinfoil on a tooth filling,” Ribey said.

CIDP, a rare disorder, typically follows an infection in the body that messes up the immune system. There is always a suspected trigger, but the exact cause can’t be pinned down.

Clark, the lead health investigator at Walkerton, said research hasn’t shown a good correlation between E. coli O157:H7 and CIDP.

“But I’m not excluding it because the reality is any inflammatory event may … contribute to the onset of an autoimmune disorder, which CIDP really is,” he said.

At first, Schnurr could “furniture walk” around his condo, using a cane and clutching at various items to keep his balance. But there were too many tumbles, too many sutures and too many broken bones. Five times, he ended up in the hospital. Once he fell into his television, pushing it through the drywall.

“When I could get out of bed, I’d go down into the living room and sit there and stare,” he said. “I wouldn’t even answer the phone.”`

When his legs got weaker, Schnurr would crawl around his home, sometimes till his knees bled. For the past decade, even that was too much.

“I would often hope and pray I would get some kind of something to make me well,” he said. “I know now that’s not going to happen and …”

The rest of that thought preoccupied his mind, he said, for almost 10 years. He wanted out of a life that hurt to live. Before assisted death became legal in Canada in 2016, he considered going to Switzerland, where it was available.

“I’m not afraid. I’m not scared. I’m almost looking … I am looking forward to it because I’ll be gone,” he said.

“I think most people, well, I know most people, they don’t want to die. They want to live, but life is no fun for me. I can’t go anywhere. I can’t do anything. My body is breaking down more and more. So I discussed it with doctors and family. They agreed with me. So here I am.”

Schnurr was resolute in his decision, approaching his own death with an almost clinical detachment — “There was never a tear,” Ribey said — as he wondered about timing and process. He said he cleaned up any debts and other paperwork so his sister wouldn’t be burdened. He got someone to throw away all his pills and he said goodbye to those who mattered.

“I’m rational. I’m in pain, but I’m always in pain,” he said. “I gave it a lot of thought. It’s not something you decide overnight.”

On his birthday on July 14, 2017, he posted on Facebook that it would be his last.

“Going back a month ago up till present, I was ticking the days off,” he said. “I just didn’t want to suffer anymore. The pain and suffering and lack of friends, you know. I’m basically here alone with the exception of the people that come in and clean.”

On the first day of May, in the afternoon, Ribey lay down next to her brother. It was time. A doctor administered three injections.

“I was lying beside him and holding his hand and he just put his head down on mine and said, ‘How’s my little sister?’ And that’s when I started to cry. Then I said something like, thank you for being such a kind brother and a good brother to me. I’m going to miss you … I told him I loved him.”

She said it was “very, very peaceful and very quick.”

For Schnurr, a man broken beyond repair, the pain stopped.