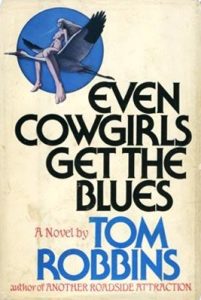

I’m a fan of Tom Robbins’ novels.

Especially his experimentation with hallucinogens and same-sex relationships in his 1976 novel, Even Cowgirls Get the Blues.

I once had a boss who declared that when he retired, he’d have a cabin with huge speakers so he could play Jimi Hendrix, and do a lot of psychedelics.

I once had a boss who declared that when he retired, he’d have a cabin with huge speakers so he could play Jimi Hendrix, and do a lot of psychedelics.

Ed Young, one of the best science writers around, writes in The Atlantic that if you were an American scientist interested in hallucinogens, the 1950s and 1960s were a great time to be working. Drugs like LSD and psilocybin—the active ingredient in magic mushrooms—were legal and researchers could acquire them easily. With federal funding, they ran more than a hundred studies to see if these chemicals could treat psychiatric disorders.

That heyday ended in 1970, when Richard Nixon signed the Controlled Substances Act. It completely banned the use, sale, and transport of psychedelics—and stifled research into them. “There was an expectation that you could potentially derail your career if you were found to be a psychedelics researcher,” says Jason Slot from Ohio State University.

For Slot, that was a shame. He tried magic mushrooms as a young adult, and credits them with pushing him into science. “It helped me to think more fluidly, with fewer assumptions or acquired constraints,” he says. “And I developed a greater sensitivity to natural patterns.” That ability inspired him to return to graduate school and study evolution, after drifting through several post-college jobs. (“They are not for everyone, they entail risks, they’re prohibited by law in many countries, and only supervised use by informed adults would be advisable,” he adds.)

I also tried magic mushrooms as a young adult, and it made me want the drug and dose to be regulated – but we’re running away from an imaginary dog on a Port Colborne waterfront.

Ironically, he became a mycologist—an aficionado of fungi. And he eventually came to study the very mushrooms that he had once experienced, precisely because so few others had. “I realized how pitifully little we still knew about the genetics and ecology of such a historically significant substance,” he says.

Why, for example, do mushrooms make a hallucinogen at all? It’s certainly not for our benefit: These mushrooms have been around since long before people existed. So why did they evolve the ability to make psilocybin in the first place?

And why do such distantly related fungi make psilocybin? Around 200 species do so, but they aren’t nestled within the same part of the fungal family tree. Instead, they’re scattered around it, and each one has close relatives that aren’t hallucinogenic. “You have some little brown mushrooms, little white mushrooms … you even have a lichen,” Slot says. “And you’re talking tens of millions of years of divergence between those groups.”

It’s possible that these mushrooms evolved the ability to make psilocybin independently. It could be that all mushrooms once did so, and most of them have lost that skill. But Slot thought that neither explanation was likely. Instead, he suspected that the genes for making psilocybin had jumped between different species.

These kinds of horizontal gene transfers, where genes shortcut the usual passage from parent to offspring and instead move directly between individuals, are rare in animals, but common among bacteria. They happen in fungi, too. In the last decade, Slot has found a couple of cases where different fungi have exchanged clusters of genes that allow the recipients to produce toxins and assimilate nutrients. Could a similar mobile cluster bestow the ability to make psilocybin?

To find out, Slot’s team first had to discover the genes responsible for making the drug. His postdoc Hannah Reynolds searched for genes that were present in various hallucinogenic mushrooms, but not in their closest non-trippy relatives. A cluster of five genes fit the bill, and they seem to produce all the enzymes necessary to make psilocybin from its chemical predecessors.

The rest of the article is available at https://www.theatlantic.com/science/archive/2017/08/how-mushrooms-became-magic/537789/?utm_source=atltw