Scott Canon of The Kansas City Star writes in a good food safety feature, go ahead and eat out. Or eat in (edited excerpts below).

Whether you dig into Mom’s casserole, feast on the local diner’s daily special or snarf up something from a mega-corporation’s drive-through, America’s meals may arrive as safe now as mankind has ever known.

Whether you dig into Mom’s casserole, feast on the local diner’s daily special or snarf up something from a mega-corporation’s drive-through, America’s meals may arrive as safe now as mankind has ever known.

Just not 100 percent.

Government rules continue to tighten. Various industries, fearful of lawsuits and the lost business that follows bad publicity, put more muscle into keeping things clean.

Yet experts also describe an increasingly elaborate system that tests the power to keep a meal safe.

“The marketplace is probably more complex,” said Charles Hunt, the Kansas state epidemiologist. “The produce that you get in the store today was in Mexico or someplace else just a few days before.”

The Chipotle chain saw multiple, high-profile problems last year. An E. coli outbreak traced to its restaurants in October. In December, the company also was tied to a norovirus incident in Boston, following outbreaks of the pathogen earlier in the year at outlets in California and Minnesota.

In the Kansas City area, more than 600 people got sick after attending shows at the New Theater Restaurant in January, and tests confirmed infections of the norovirus in at least some. It also struck at least 18 staff and patients at the University of Kansas Hospital’s Marillac Campus that month. And about a dozen people were hit with the same vomiting and diarrhea shortly afterward at a Buffalo Wild Wings in Overland Park.

Upticks in detections of outbreaks of food-borne illness, analysts say, likely reflect our increasing powers to spot them — not a growing danger.

In 1998, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration traced an outbreak of salmonella agona to a Malt-O-Meal processing plant in Minnesota. Ten years later, the same plant again shipped out cereal tainted with salmonella, sickening at least 33 people.

With the two incidents separated by a decade, any link seemed coincidental.

But a few years later, the FDA built a powerful tool for analyzing bacterial strains — Whole Genome Sequencing. It can identify down the lineage of any bacterium in its database. In this case it showed the new salmonella was the direct descendant of the earlier one.

It turned out that the first outbreak stemmed from contaminated water used to clean the plant during a renovation. That same water was mixed in with mortar for the construction. Dangerous salmonella had been preserved in that mortar. Over the years, the surface of the mortar turned to dust, got wet and gave new life to that distinct family of salmonella.

It turned out that the first outbreak stemmed from contaminated water used to clean the plant during a renovation. That same water was mixed in with mortar for the construction. Dangerous salmonella had been preserved in that mortar. Over the years, the surface of the mortar turned to dust, got wet and gave new life to that distinct family of salmonella.

Imagine the implications. The plant could prevent repeats by painting a sealant over the unlikely culprit — mortar in its walls.

But think of the child who becomes sick down the road with salmonella. The source could be any of thousands of ingredients consumed by an American kid in a normal day. But what if a doctor shares the salmonella sample with federal disease trackers? By looking at the particular genetic line, scientists can spot the family tree and the likely source.

“It tells you who’s related to who even over many years,” said Eric Brown, the director of the Division of Microbiology at the FDA’s Center for Food Safety & Applied Nutrition.

Technology, food safety experts say, only goes so far.

The bigger payoffs come from diligence. That means, foremost, avoiding contamination from feces.

“Our food safety starts on the farm,” said Doug Powell. A former Kansas State University professor of food safety, he’s now the chief author of barfblog.

“It has to be systemic, repeated and relevant.”

For starters, farmers should not use manure on fresh produce. They need to know where their irrigation supply comes from and whether runoff during heavy rains travels from feedlots or other places where livestock or farm workers defecate. Washing those fruits and vegetables later down the line is necessary, but that often can’t overcome massive exposure to E. coli and other potentially fatal bacteria that thrive in poop.

Bill Marler, a Seattle attorney who’s made a high-profile career filing lawsuits in food-borne illness cases, speaks with less alarm about the direction of Big Meat.

After years of restaurants and meat packers weathering expensive lawsuits and public relations disasters, he said, they’ve changed.

Take the slaughterhouse. Cattle arrive splattered with barnyard waste. For years, that created problems because the tainted hides would inevitably taint the skinned carcasses. But now, packing operations routinely steam-clean or treat the carcasses with an acid wash.

“You started to see an amazing turnaround and recalls linked to hamburger have fallen like a stone,” Marler said.

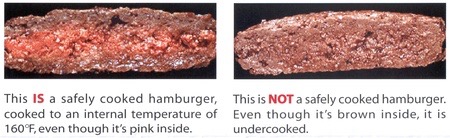

Meantime, he said, restaurants better recognize the business risk of not killing pathogens that cling to meat. Marler said big chains, in particular, devote increasing effort to thoroughly cooking beef, pork and poultry.

And federal rules on the required temperature for cooked meat have increased. Some chains, such as Taco Bell, now cook meat at centralized locations before shipping it to franchises. The local teenager preparing that food for customers still needs to be wary of temperature control, but much of the responsibility for safety has been standardized by corporate operations.

Produce, he and others say, poses a more difficult problem. Food that’s not cooked lacks the critical “kill step” to render harmless the bacteria that do slip through.

That, goes the critique, sets up a corporate culture that valued freshness over safety.

The company has responded by shutting down its restaurants repeatedly for special training days and saying its redoubled efforts to track the practices of its suppliers.

(Many have noted that much of Chipotle’s problems related to contamination from sick workers, not from its pursuit of freshness. More on that later.)

But consumers have shown an increasing interest in the source of their food, preferring fresh over processed and local or organic over cheaper commodity ingredients. That’s tied, analysts say, to the belief that food made on a smaller scale and without the use of antibiotics in livestock or pesticides in crops is safer.

But consumers have shown an increasing interest in the source of their food, preferring fresh over processed and local or organic over cheaper commodity ingredients. That’s tied, analysts say, to the belief that food made on a smaller scale and without the use of antibiotics in livestock or pesticides in crops is safer.

Some evidence suggests that such methods provide a more nutritious meal that may avoid long-term health risks. Yet they can pose new challenges in dodging food-borne pathogens in the short term, said barfblog’s Powell and others.

“Natural, organic, sustainable, dolphin-free — those are lifestyle choices,” Powell said. “There’s been no study that has conclusively said one way or another if it’s more likely to make you barf more.”

He worries it might. Smaller farms might not have the resources, or the sophistication, to keep soiled rain runoff from their vegetable patches. The farmer’s market customers or restaurants drawn to their farm-to-plate marketing, he said, might be less inclined to question safety.

“McDonald’s has it covered,” Powell said. “At the boutique places, I say I want my meat cooked to 165 degrees and they look at me like I just came off the turnip truck.”

Color is a lousy indicator and a tip-sensitive digital thermometer is required.

Color is a lousy indicator and a tip-sensitive digital thermometer is required.