From a Kansas State University press release:

When it comes to your Thanksgiving turkey, a Kansas State University food safety expert has two tips that could help keep your holiday meal safer:

* Don’t give your turkey a bath.

* Don’t give your turkey a bath.

* Always take your turkey’s temperature.

Washing the turkey before popping it in the oven may be something you saw your mom — or grandmother — do, but Doug Powell, professor of food safety, said it’s a practice where mom really didn’t know best.

“Washing the bird has long been disregarded because of the food safety risk of cross-contamination,” he said. “Do not wash that bird — you’ll spread bacteria everywhere.”

Studies have found food poisoning bacteria like campylobacter or salmonella are common on poultry carcasses and can easily be spread by the splashes from washing the bird, Powell said. That means the sink, countertops, water taps and anything else in the vicinity — including other food — can become cross-contaminated. Washing hands after handling and preparing the bird also is a must.

Once the unwashed bird is in the oven, Powell said cooks should do themselves a favor and rely on a good thermometer to let them know when the main attraction is ready. Turkey should be cooked to an internal temperature of 165 degrees. Just checking to see if the juices from the bird run clear when the bird is pricked isn’t an accurate indicator of its doneness.

“Color is a lousy indicator of safety,” Powell said. “No matter how you cook your bird, the key is to use a tip-sensitive digital thermometer to verify safety.”

To help keep foodborne illness from spoiling the Thanksgiving holiday, check out food safety infosheets, prepared by Powell and Benjamin Chapman, a food safety  specialist and assistant professor of family and consumer sciences at North Carolina State University, available at Powell’s blog:

specialist and assistant professor of family and consumer sciences at North Carolina State University, available at Powell’s blog:

* For tips on why not to bathe the bird, https://barfblog.com/infosheet/bathing-birds-is-a-food-safety-mess/.

* For tips on preventing holiday foodborne illness, https://barfblog.com/infosheet/avoid-foodborne-illness-during-the-holidays.

* For tips on holiday meal safety, https://barfblog.com/infosheet/holiday-meal-food-safety-2/.

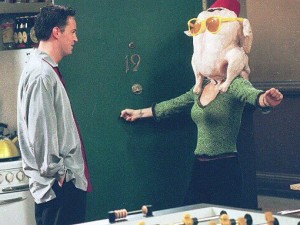

A holiday food safety video also is available at https://barfblog.com/holiday-food-safety-dont-wear-the-turkey-on-your-head-and-other-tips/. And the Spanish and French translations of the infosheets can be found athttps://barfblog.com/infosheets-esp/ and https://barfblog.com/infosheets-fra/.

prepared chicken pate in the UK.

prepared chicken pate in the UK.