Rob Mancini writes:

Food safety training is seen as an integral component in the public health system designed to reduce the likelihood of a foodborne illness.

Food safety training is seen as an integral component in the public health system designed to reduce the likelihood of a foodborne illness.

Traditional food safety training courses are administered via classroom-based programs or on-line with little to no hands-on component. If our intention as food safety professionals is to change ones’ food safety behaviors, then it is time to resort to educational psychology- what works and what doesn’t work.

Different people learn in different ways and we must address this issue. A hands-on component is necessary to instill positive correct food safety practices and to aid in memory retention. More often than none, feedback that I receive is that there is no time to do any hands-on work, the class is too long. Not true. Reduce the amount of PowerPoint slides by eliminating the “fluff” and do some hands-on work. Students will not retain 8-hours of information in the long-term.

Paul Forsyth writes in Niagara This Week:

Many Niagara residents are likely being spared the miserable physical symptoms of food poisoning thanks to mandatory food safety training for staff at places such as restaurants, banquet halls and nursing homes, regional politicians were set to hear on June 2.

The Region, which oversees public health in Niagara, pushed for years to have the province bring in mandatory food safety training in Ontario. Faced with inaction on that front, and on the heels of some high-profile outbreaks of food poisoning, the Region brought in its own mandatory training bylaw several years ago.

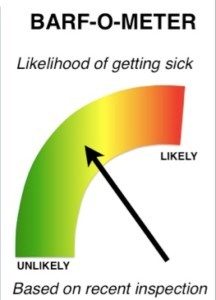

A new report to regional politicians suggests a whole lot less people are enduring the wretched vomiting and diarrhea that are hallmarks of food poisoning because of safer food handling.

Environmental health manager Chris Gaspar, who wrote the report in consultation with environmental health director Bjorn Christensen, said 459 cases of food poisoning were investigated by public health last year.

But he said it’s estimated that only about 4.4 per cent of actual food poisoning cases are reported, meaning it’s likely the number of cases in Niagara was probably closer to 10,500 last year based on that ratio.

The cost of those outbreaks is astounding. In a report last year, public health staff looked at the number of food poisoning cases of campylobacter, salmonella, E. coli 0157 and shigella — just four of about 30 commonly acquired pathogens. That report noted each case can cost about $1,068 due to medical costs and lost productivity due to people being too sick to go to work, meaning the estimated 3,273 annual poisoning cases involving those four pathogens comes with a pricetag of more than $3 million in Niagara.

But Gaspar said in his new report that the number of cases of E. coli food poisoning in Niagara have plummeted since the introduction of mandatory food safety training, dropping from two cases per 100,000 people in 2012 to just 0.2 cases per 100,000 people in 2014 — a drop of about 90 per cent.