Multistate outbreaks cause more than half of all deaths in foodborne disease outbreaks despite accounting for only a tiny fraction (3 percent) of reported outbreaks in the United States, according to a new U.S Centers for Disease Control report.

Recent outbreaks of foodborne illness linked to tainted cucumbers, ice cream and soft cheeses show the devastating consequences when food is contaminated with dangerous germs before it reaches a restaurant or home kitchen.

Recent outbreaks of foodborne illness linked to tainted cucumbers, ice cream and soft cheeses show the devastating consequences when food is contaminated with dangerous germs before it reaches a restaurant or home kitchen.

Highlights from the report on multistate foodborne outbreaks during 2010-2014 include:

• An average of 24 multistate outbreaks occurred each year, involving two to 37 states.

- Salmonella accounted for the most illnesses and hospitalizations and was the cause of the three largest outbreaks, which were traced to eggs, chicken and raw ground tuna.

- Listeria caused the most deaths, largely due to an outbreak caused by contaminated cantaloupe in 2011 that killed 33 people.

- Imported foods accounted for 18 of the 120 reported outbreaks. Food imported from Mexico was the leading source in these outbreaks, followed by food imported from Turkey.

The report recommends that local, state, and national health agencies work closely with food industries to understand how their foods are produced and distributed to speed multistate outbreak investigations. These investigations can reveal fixable problems that resulted in food becoming contaminated and lessons learned that can help strengthen food safety.

The report highlights the need for food industries to play a larger role in improving food safety by following best practices for growing, processing, and shipping foods. In addition, food industries can help stop outbreaks and lessen their impact by keeping detailed records to allow faster tracing of foods from source to destination, by using store loyalty cards to help identify what foods made people sick, and by notifying customers of food recalls.

“Reacting to problems isn’t sufficient in today’s food system, nor is it the best way to practice public health,” Dr. Kathleen Gensheimer, director of FDA’s Coordinated Outbreak Response & Evaluation Network, said in a teleconference.

Gensheimer stressed that in the past, food safety has been focused on reacting to outbreaks, but new regulations set to take effect in 2016 will require companies to take a science-based approach to building safety controls into food production.

Gensheimer stressed that in the past, food safety has been focused on reacting to outbreaks, but new regulations set to take effect in 2016 will require companies to take a science-based approach to building safety controls into food production.

“Industry is a very critical partner,” she said.

For example, although it is still not clear what caused the E. coli outbreak at Chipotle, Gensheimer said on the call that the company has shared “all of their records and is working with us in any way possible to give us information about their suppliers.”

Gensheimer also said after the current investigation ends, the company expressed interest in meeting with FDA and the CDC to work out ways to prevent future outbreaks.

CDC Director Dr. Tom Frieden said state-of-the-art disease tracking tools, and the introduction of gene tools, are helping to quickly track down the source of food-borne outbreaks in collaboration with state and national partners.

Frieden said disease detectives are “cracking the cases much more frequently than in past years because we have this new DNA fingerprinting tool being used increasingly,” but many cases still go unsolved.

He said companies are also stepping up to help, noting new requirements at Wal-Mart Stores Inc for food suppliers that set new control for suppliers to reduce contamination and the wholesaler’s Costco’s use of membership card lists to notify customers about recalled foods.

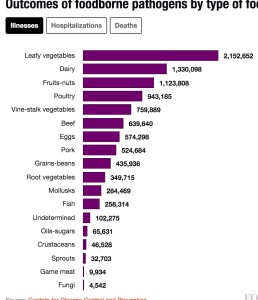

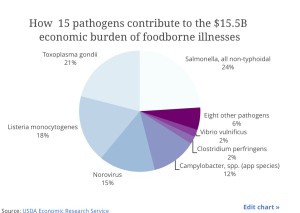

The leading causes of multistate outbreaks – Salmonella, E. coli, and Listeria – are more dangerous than the leading causes of single-state outbreaks. These three germs, which cause 91 percent of multistate outbreaks, can contaminate widely distributed foods, such as vegetables, beef, chicken and fresh fruits, and end up sickening people in many states.

“Americans should not have to worry about getting sick from the food they eat,” said CDC Director Tom Frieden, M.D., M.P.H. “Top-notch epidemiology and new gene sequencing tools are helping us quickly track down the source of foodborne outbreaks – and together with our national partners we are working with the food industry to prevent them from happening in the first place.”

Introduction: Millions of U.S. residents become ill from foodborne pathogens each year. Most foodborne outbreaks occur among small groups of persons in a localized area. However, because many foods are distributed widely and rapidly, and because detection methods have improved, outbreaks that occur in multiple states and that even span the entire country are being recognized with increasing frequency.

Methods: This report analyzes data from CDC’s Foodborne Disease Outbreak Surveillance System to describe multistate foodborne outbreaks that occurred in the United States during 2010–2014.

Results: During this 5-year period, 120 multistate foodborne disease outbreaks (with identified pathogen and food or common setting) were reported to CDC. These multistate outbreaks accounted for 3% (120 of 4,163) of all reported foodborne outbreaks, but were responsible for 11% (7,929 of 71,747) of illnesses, 34% (1,460 of 4,247) of hospitalizations, and 56% (66 of 118) of deaths associated with foodborne outbreaks. Salmonella (63 outbreaks), Shiga toxin-producing E. coli (34), and Listeria monocytogenes (12) were the leading pathogens. Fruits (17), vegetable row crops (15), beef (13), sprouts (10), and seeded vegetables (nine) were the most commonly implicated foods. Traceback investigations to identify the food origin were conducted for 87 outbreaks, of which 55 led to a product recall. Imported foods were linked to 18 multistate outbreaks.

Conclusions: Multistate foodborne disease outbreaks account for a disproportionate number of outbreak-associated illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths relative to their occurrence. Working together, food industries and public health departments and agencies can develop and implement more effective ways to identify and to trace contaminated foods linked to multistate outbreaks. Lessons learned during outbreak investigations can help improve food safety practices and regulations, and might prevent future outbreaks.

MMWR November 3, 2015 / 64(Early Release);1-5

Samuel J. Crowe, PhD1,2; Barbara E. Mahon, MD2; Antonio R. Vieira, PhD2; L. Hannah Gould, PhD

http://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm64e1103a1.htm?s_cid=mm64e1103a1_w