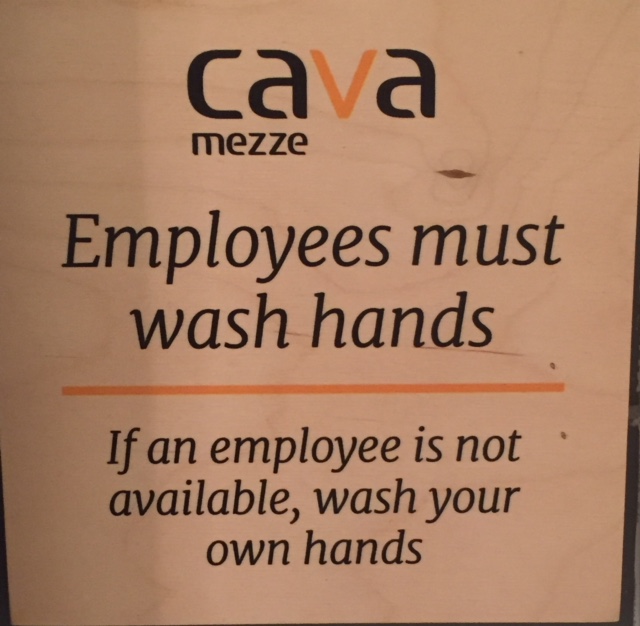

Following on all things Schaffner, a professor of food science at Rutgers, who has been studying hand washing for years and says the conventional wisdom shouldn’t be ignored.

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re peeing or you’re pooping, you should wash your hands,” he told Business Insider.

“It doesn’t matter whether you’re peeing or you’re pooping, you should wash your hands,” he told Business Insider.

Here’s why.

Germs can hang out in bathrooms for a long time

Each trip to the restroom is its own unique journey into germ land. So some occasions probably require more washing up than others.

“If you’ve got diarrhea all over your hands, it’s way more important that you wash your hands than if… you didn’t get any obvious poop on your fingers,” Schaffner said. “My gosh, if you’ve got poop on your hands and you have the time, certainly, get in there, lather up real good and do a real good job.”

Compared to feces, urine can be pretty clean when we’re not harboring any infections, though it’s not totally sterile.

“People who use urinals probably think they don’t need to wash their hands,” Michael Osterholm, director of the University of Minnesota’s Center for Infectious Disease Research and Policy, said to the New York Times. (In studies, women tend to be better about adhering to hand washing than men.)

But it’s best to wash your hands after every trip to the toilet because human feces carry pathogens like E. coli, Shigella, Streptococcus, hepatitis A and E, and more.

You can also easily catch norovirus by touching bathroom surfaces that have been contaminated with a sick person’s poo or vomit, then putting your hands into your mouth. The super-contagious illness is the most common food poisoning culprit, and causes diarrhea, vomiting, nausea and stomach pain.

A wide variety of other microbes and bacteria can be found in bathrooms, too. Some strains of Staphylococcus, or staph, are “found on almost every hand,” as a team of hand washing researchers pointed out in a 2004 study. Public toilets can house many different drug-resistant strains of that bacteria.

“I think a good general rule of thumb is you should wash your hands any time you feel that they might be dirty,” Schaffner said. In other words, seize the opportunity when you’re near a sink.

He said he’s not “super paranoid” about making sure his own hands are always squeaky clean, but some of his favorite times of day to wash up are after walking the dog, working in the dirt, or handling raw meat.

Even a quick “splash ‘n dash,” as researchers like to call the practice of rinsing with water but no soap, can help fight off some bacteria that causes infections. But that shortcut is not advised if you might have raw meat or feces on your mitts, and a lather with soap and water is more effective at disinfecting hands than any wipe or sanitizer.

Even a quick “splash ‘n dash,” as researchers like to call the practice of rinsing with water but no soap, can help fight off some bacteria that causes infections. But that shortcut is not advised if you might have raw meat or feces on your mitts, and a lather with soap and water is more effective at disinfecting hands than any wipe or sanitizer.

Here are Schaffner’s best tips for your next journey to the toilet

Follow this simple, three-step hand-washing plan to lower your chances of getting colds, self-inflicted food poisoning, and diarrhea.

First, don’t worry about the temperature of the water; Schaffner’s studies have confirmed that doesn’t make a difference. He suggests that you “adjust the water temperature so it’s a nice comfortable temperature, so you can do a good job.”

Second, give yourself enough time to “get some soap in there, lather it up real good, clean under your finger nails,” Schaffner said. Spending even five seconds washing your hands can help reduce the amount of bacteria on them, but 20 seconds is better. The Centers for Disease Control recommends humming the Happy Birthday song to yourself twice as a timer.

Third, dry off before you leave the room. This step is key because wet hands transfer more bacteria than dry ones.

“If your hands are still wet, you go to touch that door of the bathroom, having your wet hand might actually help transfer bacteria,” Schaffner said. He’ll even dry his palms on his pants if there’s no paper towel around.

Despite all the evidence demonstrating the health benefits of regular hand washing, Schaffner knows his advice can only go so far.

“I’m not in charge of you washing your hands, just because I’m a guy who did some science and did some research on hand-washing,” he said. “You do what you want.”

Well said.

We ain’t preachers, just provide evidence-based advice.

Got me a job at Kansas State University, got me dismissed.