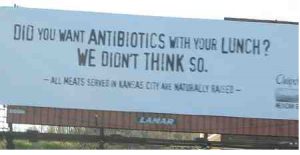

I started bashing Chipotle about 2006, when driving through Kansas City with a trailer full of stuff as I moved to Manhattan, Kansas, to follow a girl, and cited this billboard.

Any company focused on this stuff usually meant they were somewhat oblivios to basic food safety.

Any company focused on this stuff usually meant they were somewhat oblivios to basic food safety.

Unfortunately for all the thousands of sick people over the next 14 years, I was right.

I tried to call them out for the food safety amateurs they were.

Even worse, when Amy was pregnant with Sorenne, she would get Chipotle cravings and I would dutifully comply, because she was doing the heavy lifting in pregnancy.

Now I have an entire book chapter I’m working on, devoted to Chipotle.

Kevin Folta of the Genetic Literacy Project writes that after years of attacking conventional agriculture and crop biotechnology, Chipotle now seems to have found a love for the American farmer that is as warm and inviting as the gooey core of a steak burrito. With the launch of its “Cultivate the Future of Farming” campaign, the company seeks to raise awareness about the hardships facing American agriculture and offer some recommendations and seed grants to address the problems. According to the campaign website:

It’s time to take real steps to give the next generation of farmers a bright future. Through our purpose to Cultivate a Better World, we’re putting programs in place that make a real impact, including seed grants, education and scholarships, and 3-year contracts. Our vision is bold, but we’re starting with a mission to cultivate the future of farming by focusing on pork, beef, and dairy.

It is good to see a company raising awareness about these issues. But given Chipotle’s past cozy relationship with organic food marketers, this seems more like a marketing stunt to woo consumers who are growing increasingly concerned about the status of American farms, and less like a genuine example of philanthropy.

Chipotle is absolutely correct about one thing. The crisis in agriculture is real. Farmers are facing low prices for their products, astronomical costs, and strangling regulation. Farms, from commodity crops to dairies, are going out of business daily. Farmer suicides are a barometer of how severe the problem is.

From Chipotle’s website- The “challenge is real” and “It’s a hard living.”

However, Chipotle’s new ag-vertisment seems too little, too late. The threats to farmers and the public’s negative perception of agriculture didn’t seem to bother the company just a few years ago. For example, it’s 2014 video Farmed and Dangerous was an assault on large-scale animal agriculture, the industry that produces the ingredients that go into Chipotle’s burritos. Farmed and Dangerous was not the restaurant chain’s first effort, either. The video short The Scarecrow falsely depicted a sad, dystopian world of dairy production in which forlorn cows are locked in stacked metal boxes as milk is extracted by an extensive network of plumbing.

And of course, Chipotle’s penetrating campaign against genetic engineering (GE) sought to capitalize on the momentum of several failed GMO labeling efforts, which were designed to demonize crop biotechnology by suggesting to consumers that GE seeds were dangerous—an allegation known to be false.

Let’s get real. Chipotle’s decisions to criticize agriculture and then embrace it were not born of altruism. Public-facing corporate positions are spawned from focus groups and surveys. As a multinational, billion-dollar food empire, Chipotle is no different. The company’s ad campaigns aim to reinforce consumers’ perceptions and identity, showing that Big Burrito shares their values. That is what we see in this latest pro-farm campaign. The public is becoming increasingly aware of the fragile state of US agriculture and the crisis that has hit rural North America hard, and Chipotle is responding.

So is “Cultivate the Future of Farming” just an ag-washing ornament to exploit farmer hardship, or is this a genuine change of heart?

If it is indeed the latter, it needs to start with an apology—an honest one. Chipotle needs to publicly reject its anti-science positions and profound misrepresentation of agriculture. In the six years since the fast food chain’s anti-farming efforts hit a feverish pace, public perception has changed. The fear-based misinformation campaigns are failing, and time has not treated such efforts well. Chipotle’s videos are a shameful reminder of the rhetoric that was so prevalent just a short time ago.

Imagine where we’d be today if in 2014 Chipotle and other brands invested heavily in research, rural mental health, or resources to bring precision agriculture to farmers. I think the perception of Chipotle and the perception of crop and animal production would be very different.

Perhaps the most important takeaway is that you shouldn’t bite the hand that feeds in the first place. Targeting farmers who produce the products you sell is bad business—and it threatens a critical industry we all depend on.