What is the most effective way to provide information about how food was grown and prepared?

I’ve been touting the same approach to food safety information for over 20 years: figure out the best and most meaningful way to provide open access; embrace new technology, and no one wants to be the politician who tells constituents, no, you don’t deserve to know.

I’ve been touting the same approach to food safety information for over 20 years: figure out the best and most meaningful way to provide open access; embrace new technology, and no one wants to be the politician who tells constituents, no, you don’t deserve to know.

Restaurant inspection results should be disclosed as local communities are discovering around the world; but what’s the best way? We do research on that.

People say they want to know if something is genetically modified; I prefer genetic engineering, because all food is genetically modified in some manner, and sold sweet corn as GE 16 years ago.

No biggie.

Technology seems to have caught up with my democratic dreams and food information is about to flood the mainstream.

The UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) has agreed with the food industry to publish the results of industry testing of meat products, to provide a clearer picture of standards in the food chain. The results will also be made publicly available.

UK Nestle is preparing to give people instant access to information about the nutritional profile and environmental and social impacts of its products. Anyone who buys a multi-pack of two-finger Kit Kat chocolate bars in the U.K. and Ireland will be able to find out more about what they are made of, how they fit into a balanced diet and lifestyle, and how they were produced, just by scanning the packaging with a smartphone.

UK Nestle is preparing to give people instant access to information about the nutritional profile and environmental and social impacts of its products. Anyone who buys a multi-pack of two-finger Kit Kat chocolate bars in the U.K. and Ireland will be able to find out more about what they are made of, how they fit into a balanced diet and lifestyle, and how they were produced, just by scanning the packaging with a smartphone.

And Food Quality News reports that bakery manufacturers who want to differentiate themselves in a competitive market should consider communicating safety and quality efforts to consumers.

We do research on that too.

But Hershey’s Kisses?

Why not.

Dan Charles of NPR asks, can big food win friends by revealing its secrets?

The special holiday version of Hershey’s Kisses, now on sale nationwide, is an icon of the food industry’s past, and perhaps also a harbinger of its future.

Back when Milton Hershey started making this product, more than a century ago, it was a simpler time. He ran the factory and the sales campaigns — although, for decades, he refused to advertise.

Today, The Hershey Company is a giant enterprise with factories around the globe. It owns food companies in China, Brazil and India.

That’s typical for the food industry, of course. Lots of food companies are huge. And with vastly increased scale comes growing skepticism about what those companies are up to.

Amanda Hitt may be an extreme case. She’s director of the Food Integrity Campaign for an activist organization called the Government Accountability Project, which tries to expose the food industry’s darkest secrets: dangerous slaughterhouses, contaminated meat and exploited workers. “This industry is almost always wrong, and always doing something messed up,” she says. “So yeah, when I look at anything they do, there’s a certain level of skepticism.”

Amanda Hitt may be an extreme case. She’s director of the Food Integrity Campaign for an activist organization called the Government Accountability Project, which tries to expose the food industry’s darkest secrets: dangerous slaughterhouses, contaminated meat and exploited workers. “This industry is almost always wrong, and always doing something messed up,” she says. “So yeah, when I look at anything they do, there’s a certain level of skepticism.”

Charlie Arnot, who has studied consumer attitudes as a consultant to big food companies, says consumers have lots of questions: How is this food made? Is it good for me? And they tend not to trust answers from big companies.

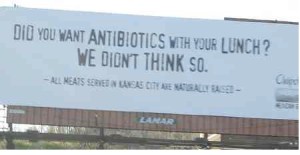

“There is a significant bias against Big Food,” says Arnot, who is also CEO of the nonprofit Center for Food Integrity in Kansas City. “In fact, the larger the company, the more likely it is that people will believe that it will put profit ahead of the public interest.”

Companies can’t change that with marketing campaigns, he says. The one thing that they can do — and the only thing that works, according to Arnot’s research — is open up, and reveal details of their operations.

Which brings us back to those Hershey’s Kisses.

Deb Arcoleo, who carries the freshly minted title of director of Product Transparency for The Hershey Company, has brought a bag of them along to our meeting, because there’s something new on that package. Printed on the bag, so small that you’d easily miss it, is a little square QR code. These are the codes that you now see in lots of places, like airline boarding passes.

Arcoleo takes my smartphone, aims it at the code, and I hear a beep. Suddenly, the screen of my phone is filled with information about these Hershey’s Kisses: nutrition facts, allergens in this product and details about all the ingredients. Lecithin, for instance.

“Let’s say I don’t really know what lecithin is,” says Arcoleo. “I can click on ‘lecithin,’ and I will get a definition.”

Tap another tab, and we see a note about whether this product contains ingredients from genetically modified organisms, or GMOs.

Hershey’s created this system, called SmartLabel, but other companies are now adopting it, too. Very soon, Arcoleo says, there will be tens of thousands of products on supermarket shelves with SmartLabel codes.

Charlie Arnot, the food industry consultant, thinks that some companies may, in fact, be willing to do this. Consumers are forcing them to do it.

“Consumers are interested in the good, the bad and the ugly,” he says. They are saying, “Give me the information, treat me like an adult, and allow me to make an informed choice.”

Arnot is telling big food companies that “transparency builds trust,” and advising them to post on their websites documents that may contain bad news, such as outside audits of their food safety procedures.

But outside audits and inspections can suck; more of a corporate gladhanding to move product out the door.

There are good companies and there are bad companies: Hard to tell the difference when the same soundbites are manufactured in a factory somewhere that has probably been outsourced.

The best farmers, processors, retailers and restaurants should brag about their superior food safety and whatever technology they use to make safe, wholesome food.

Brag about it; embrace it, make it your own.