A couple of weeks ago the NC State Fair wrapped up. I’ve documented my home food preservation involvement, but fairs often include lots of animal/person interaction too.

And zoonoses risks comes with the territory. There are lots and lots of petting zoo, fair, animal exhibit illnesses and outbreaks. Here’s a spreadsheet with some highlights.

Public health folks in Utah are investigating a bunch of illnesses that look like they are linked to visiting these interaction exhibits:

Utah public health officials are investigating an increase in Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli (STEC) infections across the state. While the source of these infections has not been identified, several ill individuals reported visiting petting zoos, corn mazes, and farms.

Since October 1, 2018, 20 cases of STEC have been reported along the Wasatch Front and in the Central and Southwestern regions of Utah. Cases range in age from 10 months to 71 years old. Eleven cases are younger than 18. Six people were hospitalized and no deaths have been reported. “For the past five years, Utah has averaged about 13 cases of STEC during the month of October,” said Kenneth Davis, epidemiologist with the Utah Department of Health (UDOH). “An average of 113 STEC cases and 25 hospitalizations are reported each year in Utah. This increase in October is higher than normally expected,” said Davis. UDOH is working with Utah’s local health departments to investigate the illnesses and determine the source of infection.

A 2015 MMWR article showed a lot of the disease risk stuff needs to be taken care of before with good planning and procedures. Yeah, hand washing matters, but so does not letting kids bring lunch/snacks into a contaminated environment.

Or serving food directly in the barn to a 1,000 kids.

According to Curren et al.,

During April 20–June 1, 2015, 60 cases (25 confirmed and 35 probable) were identified (Figure). Eleven (18%) patients were hospitalized, and six (10%) developed hemolytic uremic syndrome. No deaths occurred. Forty primary cases were identified in 35 first-graders, three high school students, one parent, and one teacher who attended the event. Twenty secondary cases were identified in 14 siblings, four caretakers, and two cousins of attendees.

Food was served inside the barn to adolescents who set up and broke down the event on April 20 and April 24. During April 21–23 approximately 1,000 first-grade students attended the event, which included various activities related to farming.

Animals, including cattle, had been exhibited in the barn during previous events. Before the dairy education event, tractors, scrapers, and leaf blowers were used to move manure to a bunker at the north end of the barn. Environmental samples collected in this area yielded E. coli O157:H7 PFGE patterns indistinguishable from the outbreak strains.

Although it might not be possible to completely disinfect barns and areas where animals have been kept, standard procedures for cleaning, disinfection, and facility design should be adopted to minimize the risk for exposure to pathogens (1). These environments should be considered contaminated and should not be located in areas where food and beverages are served. Hands should always be washed with soap and clean running water, and dried with clean towels immediately upon exiting areas containing animals or where animals have been kept previously, after removing soiled clothing or shoes, and before eating or drinking. Event organizers can refer to published recommendations for preventing disease associated with animals in public settings.

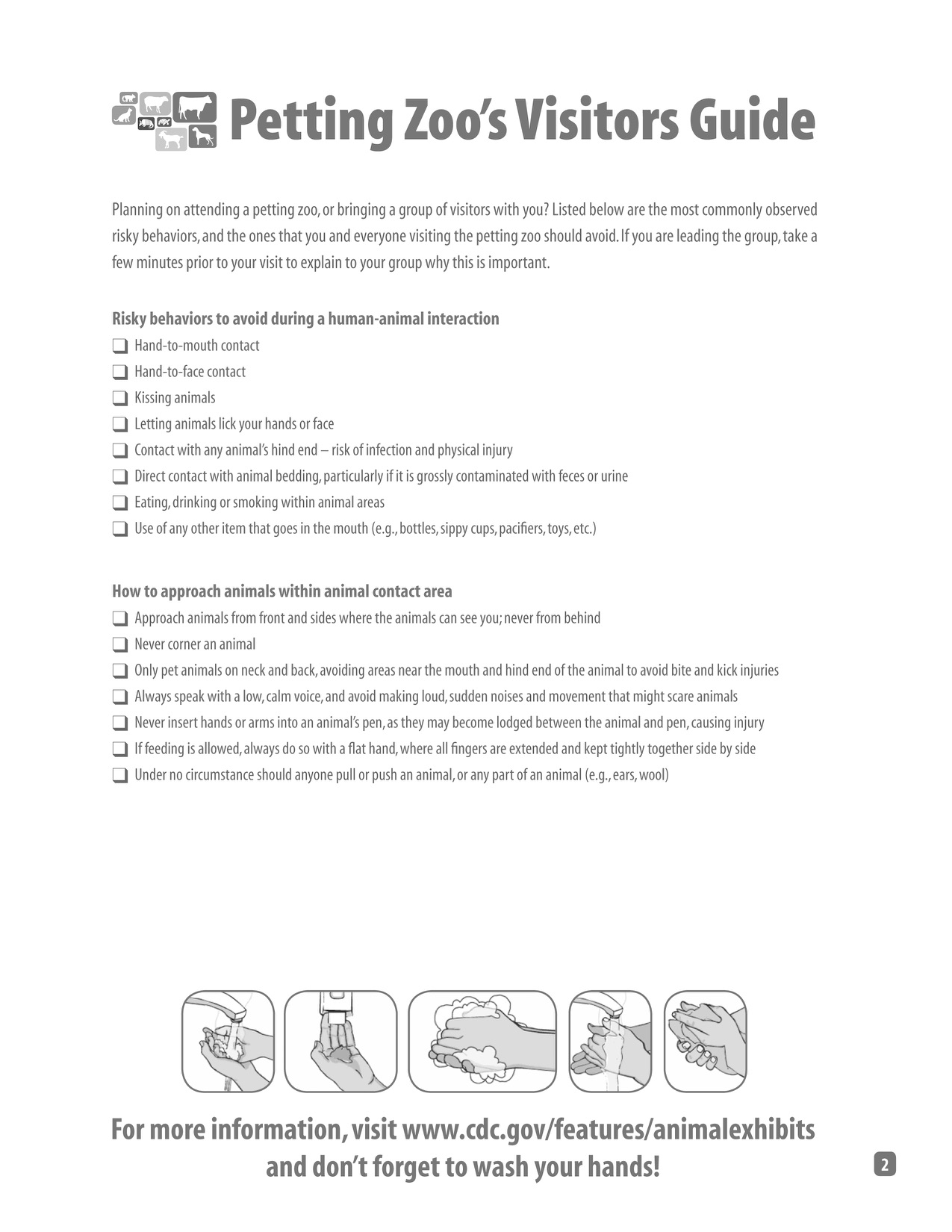

Here’s a set of guidelines we came up with for folks to use when choosing whether to take a trip to these animal events. (from: G. Erdozain , K. KuKanich , B. Chapman and D. Powell. 2015. Best practices for planning events encouraging human-animal interactions. Zoonoses and Public Health 62:90-99).