Susan Berfield of Bloomberg Business writes in Business Week that Chris Collins is a 32-year-old Web developer and photographer who lives in Oregon, just outside Portland.

He and his wife are conscientious about their food: They eat organic, local produce and ethically raised animals. Collins liked to have a meal at Chipotle once a week. On Friday evening, Oct. 23, he ordered his regular chicken bowl at his usual Chipotle in Lake Oswego. His dinner was made of 21 ingredients, including toasted cumin, sautéed garlic, fresh organic cilantro, finely diced tomatoes, two kinds of onion, romaine lettuce, and kosher salt. It tasted as good as always.

He and his wife are conscientious about their food: They eat organic, local produce and ethically raised animals. Collins liked to have a meal at Chipotle once a week. On Friday evening, Oct. 23, he ordered his regular chicken bowl at his usual Chipotle in Lake Oswego. His dinner was made of 21 ingredients, including toasted cumin, sautéed garlic, fresh organic cilantro, finely diced tomatoes, two kinds of onion, romaine lettuce, and kosher salt. It tasted as good as always.

By the next night, Collins’s body was aching and his stomach was upset. Then he began experiencing cramping and diarrhea. His stomach bloated. “Moving gave me excruciating pain,” he says, “and anytime I ate or drank it got worse.” His diarrhea turned bloody. “All I was doing was pooping blood. It was incredibly scary.” After five days, he went to an urgent-care clinic near his home; the nurse sent him to an emergency room. He feared he might have colon cancer.

On Halloween, the ER doctor called him at home: Collins had Shiga-toxin-producing E. coli 026, and he’d likely gotten it from one of those 21 ingredients in his meal at Chipotle. (This was later confirmed by public-health officials.) The doctor warned him that kidney failure was possible; intensive treatment, including dialysis, could be necessary. His kidneys held up, but it took an additional five days for the worst of Collins’s symptoms to ease and nearly six weeks for him to recover. He still doesn’t have as much physical strength as he used to, and he feels emotionally shaky, too. “Before, I was doing the P90X workouts. For a long time after, I couldn’t even walk a few blocks,” he says. “It made me feel old and weak and anxious.” On Nov. 6, Collins sued Chipotle, seeking unspecified damages.

Collins was among 53 people in nine states who were sickened with the same strain of E. coli. “I trusted they were providing me with ‘food with integrity,’ ” Collins says, sarcastically repeating the company motto. “We fell for their branding.” Chipotle’s public stance during the outbreak irritated him, too. The company closed all 43 of its restaurants in Oregon and Washington in early November to try to identify the source of the E. coli and sanitize the spaces. Notices on restaurant doors generally referred to problems with the supply chain or equipment. But local media reported that at least one restaurant in Portland put up a note that said, “Don’t panic … order should be restored to the universe in the very near future.” “That felt so snarky,” Collins says. “People could die from this, and they were so smug.”

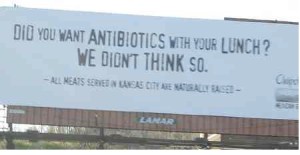

For a long time, smug worked pretty well for Chipotle Mexican Grill. It’s grown into a chain of more than 1,900 locations, thanks in part to marketing—including short animated films about the evils of industrial agriculture—that reminds customers that its fresh ingredients and naturally raised meat are better than rivals’ and better for the world. The implication: If you eat Chipotle, you’re doing the right thing, and maybe you’re better, too. It helped the company, charging about $7 for a burrito, reach a market valuation of nearly $24 billion. Its executives seemed to have done the impossible and made a national fast-food chain feel healthy.

For a long time, smug worked pretty well for Chipotle Mexican Grill. It’s grown into a chain of more than 1,900 locations, thanks in part to marketing—including short animated films about the evils of industrial agriculture—that reminds customers that its fresh ingredients and naturally raised meat are better than rivals’ and better for the world. The implication: If you eat Chipotle, you’re doing the right thing, and maybe you’re better, too. It helped the company, charging about $7 for a burrito, reach a market valuation of nearly $24 billion. Its executives seemed to have done the impossible and made a national fast-food chain feel healthy.

Fewer people associate Chipotle with “healthy” now. Three months before Collins was infected with E. coli, five people fell ill eating at a Seattle-area restaurant. By the time local health officials had confirmed a link, the outbreak was over, so no one said anything. In August, 234 customers and employees contracted norovirus at a Chipotle in Simi Valley, Calif., where another worker was infected. Salmonella-tainted tomatoes at 22 outlets in Minnesota sickened 64 people in August and September; nine had to be hospitalized. Norovirus struck again in late November: More than 140 Boston College students picked up the highly contagious virus from a nearby Chipotle, including half of the men’s basketball team. An additional 16 students and three health-care staff picked it up from the victims. The source? A sick worker who wasn’t sent home although Chipotle began offering paid sick leave in June. In the second week of December, when Chipotle should have been on highest alert, a Seattle restaurant had to be briefly shut down after a health inspection found that cooked meat on the takeout line wasn’t being kept at a high enough temperature. And in the most recent case, on Dec. 21, the CDC announced it was investigating an outbreak of what seems to be a different and rare version of E. coli 026 that’s sickened five people in two states who ate at Chipotle in mid-November. The company says it had expected to see additional cases. It still doesn’t know which ingredients made people ill.

Almost 500 people around the country have become sick from Chipotle food since July, according to public-health officials. And those are just the ones who went to a doctor, gave a stool sample, and were properly diagnosed. Food-safety experts say they believe with any outbreak the total number of people affected is at least 10 times the reported number. The CDC estimates that 48 million Americans get sick from contaminated food every year.

At Chipotle, three different pathogens caused the five known outbreaks. That wasn’t inevitable or coincidental. “There’s a problem within the company,” says Michael Doyle, the director of the center for food safety at the University of Georgia. Chipotle has gotten big selling food that’s unprocessed, free of antibiotics and GMOs, sometimes organic, sometimes local. “Blah, blah, blah,” says Doug Powell, a retired (I’m not dead yet) food-safety professor and the publisher of barfblog.com. “They were paying attention to all that stuff, but they weren’t paying attention to microbial safety.” Whatever its provenance, if food is contaminated it can still make us sick—or even kill. Millennials may discriminate when they eat, but bacteria are agnostic.

At Chipotle, three different pathogens caused the five known outbreaks. That wasn’t inevitable or coincidental. “There’s a problem within the company,” says Michael Doyle, the director of the center for food safety at the University of Georgia. Chipotle has gotten big selling food that’s unprocessed, free of antibiotics and GMOs, sometimes organic, sometimes local. “Blah, blah, blah,” says Doug Powell, a retired (I’m not dead yet) food-safety professor and the publisher of barfblog.com. “They were paying attention to all that stuff, but they weren’t paying attention to microbial safety.” Whatever its provenance, if food is contaminated it can still make us sick—or even kill. Millennials may discriminate when they eat, but bacteria are agnostic.

“Food with integrity,” a promise to Chipotle’s customers and a rebuke to its competitors, has become the source of much schadenfreude among both. Chipotle’s stock has lost about 30 percent of its value since August. Sales at established stores dropped 16 percent in November, and executives expect a decline of 8 percent to 11 percent in comparable-store sales for the last three months of the year. That would be the first quarterly decline for Chipotle as a public company.

Steve Ells, Chipotle’s founder and co-chief executive, went on the Today show on Dec. 10, apologized to everyone who’d fallen ill, and announced a comprehensive food-safety program that he said would far exceed industry norms. He didn’t address why a company that had challenged quality standards with such gusto hadn’t taken on safety standards as well.

On Dec. 17, speaking by phone in New York, he’s still on message, describing the Seattle restaurants he visited as clean and organized. “I ate delicious food there,” he says. “Traffic was slow, but we’re ready for people to come back. There is no E. coli in Chipotle. ” To hear Ells tell it, the company is witnessing an outbreak of excitement. He says the chain’s suppliers are excited to participate in the new safety programs; employees at headquarters in Denver are excited to contribute however they can; it’s “a very, very exciting time for us to be pushing the boundaries” on food safety. “We’re embracing this as an opportunity.”

Ells studied art history in college, trained as a chef at the Culinary Institute of America, and opened the first Chipotle in Denver in 1993 with a loan from his father. He set up a model—open kitchen, fresh ingredients, real cooking in the back, and an assembly line in front, allowing customization and speed—that’s become its own industry standard. Chipotle grew from 489 restaurants and revenue of $628 million in 2006, when it went public, to about 1,800 restaurants and $4.1 billion in revenue in 2014. Net profit increased 60 percent from 2012 to 2014. Ells and his co-CEO, Montgomery Moran, together earned more than $140 million in total compensation during that time. And Michael Pollan, the good-food arbiter, said that Chipotle was his favorite fast-food chain and that he didn’t have a second.

The company was influenced in ways it doesn’t always admit by the biggest, most industrialized chain of them all: McDonald’s. The company invested about $340 million in Chipotle from 1998, when it had 13 restaurants in Colorado, until 2006, when the two parted ways. McDonald’s taught Chipotle supply-chain economics. Chipotle often derides fast-food chains and their factory farms, enlisting the likes of Willie Nelson to make plaintive music videos about crop chemicals and steroidal cattle. But Ells respects McDonald’s size. In an interview with Bloomberg in 2014, he said Chipotle could one day be “bigger than McDonald’s in the U.S. I mean, that’s not an unreasonable way to think about this.”

And so much more. Great story

.