Food safety and public health folks are pretty good at writing proposals and getting funds to do research and usually because of a funder’s requirement to take something to the people, add on some component outreach throwaway activity to make something. Usually it is a brochure, or posters, or a website where the outputs of research are shared.

And they often suck. Because folks who are good at one type of research may forget that there are other disciplines where data gets generated on what works and why.

At one of my first IAFP meetings over a decade ago I sat through a 3-hour session of cleaning and sanitation in processing environments and each speaker ended their talk with the same type of message we all need to edumacate better. And no one mentioned evaluation.

There’s about 10,000 papers in the adult education, behavioral science and preventive health world that set the stage on how to actually make communication and education interventions that might work – many are based on behavioral theory – the kind of thing that comes from, experiments, data, critique, disagreement, repetition and replication.

The literature has some common tenants: know thy audience; have an objective; base your message on some sort of evidence; ground the approach in theory and evaluate.

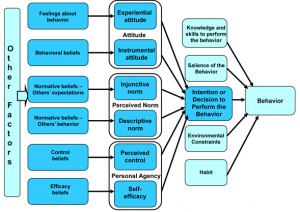

A particular favorite of mine is the Integrated Behavioral Model. It takes the Theory of Planned Behavior, adds some bells and whistles and gives something for folks to base their materials on. It’s not simple.

The good stuff rarely is.

Today we picked up something in our feeds coming from a public health group in the UK, that says making good intervention are easy. They even have a fun name for it, the EAST framework (which stands for Easy, Attractive, Social and Timely).

The first principle of the EAST framework is to make the desired behaviour easy. Small food businesses can help make healthier eating easier by:

Harnessing defaults

We have a tendency to stick with the status quo or the pre-set option. For this reason ensuring the healthiest option is the default option is a powerful tool for changing consumption behaviour. The healthier default, for example, could be offering a food item like a default side-salad instead of chips, or it could be a default portion size, like a small coffee as the default rather than a large size.

Decreasing the ‘hassle factor’

We can be deterred from a behaviour by seemingly small barriers. Decreasing the hassle factor by, for example, placing healthier drinks at the front of the fridge and sugar sweetened beverages at the back may prompt people to select the healthier option.

Utilising substitution

It is easier for us to substitute a similar behaviour than to eliminate an entrenched one. For this reason, reformulation of products (such as cooking food in rapeseed oil, making fatter chips or using low-fat spread) allows customers to engage in similar behaviours (still buying chips) but for the behaviour to be healthier.

Sounds easy. Lets see it in practice. And evaluate it.