Hawaii has joined other states in providing restaurant inspection data online, New Yorkers are debating whether inspections and reviews of Chinese and other ethnic restaurants are racist, and Canada is once again lauding Toronto’s red-yellow-green system of disclosure.

Strangely absent in such debate is the state of Minnesota, which is often praised for its skill and speed investigating outbreaks of foodborne illness.

Strangely absent in such debate is the state of Minnesota, which is often praised for its skill and speed investigating outbreaks of foodborne illness.

According to Eric Roper of the Star Tribune, Minnesota is one of the least transparent states in the nation with regard to restaurant inspections.

A local developer posted Minneapolis restaurant inspections to the Web several years ago, but ultimately took the site down after trouble getting up-to-date data from the city. The city’s health department said it hopes to have this data live in 2016, though it had similar goals in 2013.

With regard to letter grades in particular, the city’s Environmental Health Manager Dan Huff is not a fan.

“What we have found is that jurisdictions that do have grades, more resources go into fighting over the grade than actually improving food safety,” Huff said.

He believes it would be detrimental to the inspection process. “It creates a more adversarial relationship with the inspector,” Huff said. “Because you’re like ‘Come on! I just need one point so I’m an A. Give me a break man.’”

Council Member Andrew Johnson, meanwhile, has asked staff to explore the idea further.

“Making it so people can go out to the website and look up restaurants is … a great step,” Johnson said. “But it also would be even better to have higher visibility that incentivizes businesses to put safety first and health first.”

Professor Craig Hedberg, a foodborne illness expert at the University of Minnesota, said there has not been much research into the effectiveness of various grading systems.

Not all cities are convinced by letter grades. Baltimore ditched a proposal last year to adopt them, over concerns that it would negatively impact restaurants.

Peter Oshiro, manager of Hawaii’s food safety inspection program, said “We’re taking transparency to an entirely new level,” adding that, “Information from the inspection reports empowers consumers and informs their choices. … This should be a great catalyst for the industry to improve their food safety practices and make internal quality control a priority before our inspections.”

Peter Oshiro, manager of Hawaii’s food safety inspection program, said “We’re taking transparency to an entirely new level,” adding that, “Information from the inspection reports empowers consumers and informs their choices. … This should be a great catalyst for the industry to improve their food safety practices and make internal quality control a priority before our inspections.”

Filion, K. and Powell, D.A. 2009.

The use of restaurant inspection disclosure systems as a means of communicating food safety information.

Journal of Foodservice 20: 287-297.

The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30% of individuals in developed countries become ill from food or water each year. Up to 70% of these illnesses are estimated to be linked to food prepared at foodservice establishments. Consumer confidence in the safety of food prepared in restaurants is fragile, varying significantly from year to year, with many consumers attributing foodborne illness to foodservice. One of the key drivers of restaurant choice is consumer perception of the hygiene of a restaurant. Restaurant hygiene information is something consumers desire, and when available, may use to make dining decisions.

Filion, K. and Powell, D.A. 2011. Designing a national restaurant inspection disclosure system for New Zealand. Journal of Food Protection 74(11): 1869-1874 .

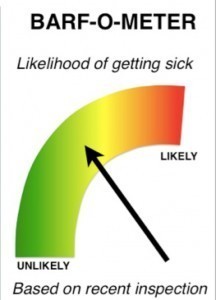

The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30% of individuals in developed countries become ill from contaminated food or water each year, and up to 70% of these illnesses are estimated to be linked to food service facilities. The aim of restaurant inspections is to reduce foodborne outbreaks and enhance consumer confidence in food service. Inspection disclosure systems have been developed as tools for consumers and incentives for food service operators. Disclosure systems are common in developed countries but are inconsistently used, possibly because previous research has not determined the best format for disclosing inspection results. This study was conducted to develop a consistent, compelling, and trusted inspection disclosure system for New Zealand. Existing international and national disclosure systems were evaluated. Two cards, a letter grade (A, B, C, or F) and a gauge (speedometer style), were designed to represent a restaurant’s inspection result and were provided to 371 premises in six districts for 3 months. Operators (n = 269) and consumers (n = 991) were interviewed to determine which card design best communicated inspection results. Less than half of the consumers noticed cards before entering the premises; these data indicated that the letter attracted more initial attention (78%) than the gauge (45%). Fifty-eight percent (38) of the operators with the gauge preferred the letter; and 79% (47) of the operators with letter preferred the letter. Eighty-eight percent (133) of the consumers in gauge districts preferred the letter, and 72% (161) of those in letter districts preferring the letter. Based on these data, the letter method was recommended for a national disclosure system for New Zealand.