An elderly woman in Phoenix. A Toledo toddler. An accountant in Indianapolis. All poisoned by food. Quickly uncovering that their illnesses are connected can make all the difference in halting a deadly

outbreak.

About 276,000 cases of foodborne illness are avoided each year because of PulseNet, a 20-year-old network coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, new research has found. PulseNet links U.S. public health laboratories so that they can speedily share details about E. coli, Salmonella and other bacterial illnesses.

About 276,000 cases of foodborne illness are avoided each year because of PulseNet, a 20-year-old network coordinated by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, new research has found. PulseNet links U.S. public health laboratories so that they can speedily share details about E. coli, Salmonella and other bacterial illnesses.

The averted illnesses translate to $507 million in annual savings on medical bills and lost productivity, according to a study led by Robert L. Scharff of The Ohio State University and Craig Hedberg of the University of Minnesota.

PulseNet has created a climate that encourages better business practices and swift response to trouble, Scharff said, and that likely explains most of the avoided illnesses in the study.

In the face of public scrutiny, lawsuits and lost revenue, businesses have responded with better self-policing, he said.

“Companies are saying, ‘We can’t have this risk. This risk is too big for us,'” said Scharff, an associate professor of consumer sciences.

“What’s exciting for me is this shows the power of information in the market to force change on industry. It’s not just a way of tracking illness, but of allowing markets to work better.”

Scharff worked with experts from the CDC and elsewhere to assign a value to PulseNet, both in terms of illnesses prevented and dollars saved. The team analyzed data from 1994 to 2009.

The results, published in conjunction with PulseNet’s 20th anniversary, appear in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine.

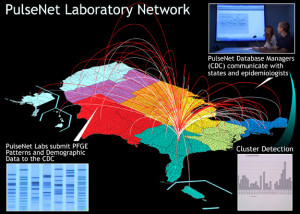

PulseNet’s annual price tag is $7.3 million, according to the analysis. The network includes 83 state and federal laboratories where microbiologists uncover DNA fingerprints of illness-causing bacteria that tie cases together and confirm outbreaks.

PulseNet’s annual price tag is $7.3 million, according to the analysis. The network includes 83 state and federal laboratories where microbiologists uncover DNA fingerprints of illness-causing bacteria that tie cases together and confirm outbreaks.

“If more agencies used information as a tool instead of trying to fight the markets, I think we would all be better off,” said Scharff, also an economist who is part of Ohio State’s Food Innovation Center.

Tainted food is responsible for about 48 million illnesses, 128,000 hospitalizations and 3,000 deaths in the United States each year.

PulseNet’s purpose is to use DNA fingerprinting techniques to link illnesses that are likely to have a shared cause, even if the cases are widely dispersed. Food moves far and wide in the modern world and the first clues of an outbreak aren’t always clustered geographically.

Until now, health officials have not been able to assign a value to the service.

“PulseNet has been very impactful. We’ve known this for many years, but it’s been anecdotal. This gives us some hard figures,” said John Besser, deputy chief of the CDC’s enteric diseases laboratory branch.

PulseNet identifies about 1,750 clusters of disease a year, including nearly 250 that span multiple states.

“PulseNet is an integral part of our food-safety system and it helps improve the quality and safety of all the food that we eat,” said Besser, who formerly worked with PulseNet in Minnesota, one of the first states to embrace the program.

“Part of that effect is containing outbreaks, but a really significant portion of the benefit is giving feedback to the food industry and the regulatory agencies so they can make food safer,” he said.

Besser said he’s hopeful the federal government will be able to sustain PulseNet as changes in laboratory testing methods evolve. Placing a value on the service should help, he said.

To participate in PulseNet, state, county and city labs evaluate samples from people sickened by food and look for the DNA fingerprint of the bacteria, molecular subtyping that goes deeper than simply naming the responsible pathogen.

Salmonella cases, for example, arise all the time. And most are sporadic, meaning the strain of bacteria in one person’s stool sample isn’t likely to match the strain in the sample across town, or across the country. When they do match, there could be big trouble.

Salmonella cases, for example, arise all the time. And most are sporadic, meaning the strain of bacteria in one person’s stool sample isn’t likely to match the strain in the sample across town, or across the country. When they do match, there could be big trouble.

Scharff and his colleagues found that in states that put more DNA data into the system, the chance of future illnesses declined significantly.

Their work focused on E. coli, Listeria and Salmonella – the bacteria that have been analyzed by the network the longest. The team used two models. One was designed to capture indirect effects of PulseNet – the food contamination that never happened because the network exists.

This was possible because states have adopted PulseNet to differing degrees and at different times, opening the door for a calculation based on how rates of illness differ by PulseNet participation level.

“The more that a state uploads into the system, the lower reported illnesses will be,” Scharff said.

The second model estimated the direct effects of product recalls when outbreaks arise and are linked to a specific food. Faster identification of outbreaks, resulting in more timely recalls, led to 16,994 fewer Salmonella cases and 2,819 fewer E. coli cases a year at a savings of $37 million, the study found.

Though the study provides estimates of illness reduction, it’s unclear how many illnesses are being prevented because of improvements in fields, factories and slaughterhouses or how many are avoided due to better-informed government and consumer actions.

It is also impossible to know about spillover effects – reductions in foodborne illnesses from pathogens not included in this analysis.

“The calculations probably underestimate the impact of PulseNet,” Scharff said. “We did not examine whether illnesses from pathogens outside of the three in question were reduced as a result of industry efforts, though they likely were.”

The economic model also may not fully include all of the costs.

“We used a very conservative economic method of measuring health costs,” he said. The study did not assign a dollar value to losses from premature death and reduced quality of life, a number that could be quite large, the researchers wrote.

On the other side, “we aren’t able to estimate the cost to industry from remedial actions,” he said. “These could be significant for affected companies, but are lower than the costs of having foodborne illnesses associated with their products.”