Friend of the barflog.com, Michael Batz, who researches food safety risk and policy at the University of Florida Emerging Pathogens Institute, and hasn’t shaved in awhile (find him on Twitter at @mbbatz) writes about a recent publication he co-authored, Economic burden of major foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States.

New numbers! We have some new numbers! (Everybody loves numbers!)

New numbers! We have some new numbers! (Everybody loves numbers!)

In a report posted online yesterday, the USDA Economic Research Service put the economic burden of fifteen foodborne pathogens at $15.5 billion per year. That’s a lot of scratch.

But haven’t we been here before?

The new report simply puts some writing and analysis around the numbers ERS put out last year in the form of detailed data tables for these same pathogens. (I’m a distant third author on this report, mostly because Sandy Hoffmann is so generous; ERS did a lot of work here to update and improve estimates Sandy and I developed a few years ago, as part of our Ranking the Risks report and related journal articles).

It’s been a busy year for foodborne illness “burden of disease” studies. Earlier this year, FDA economists published their own estimates of the annual costs of foodborne illness, while CDC published estimates of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) for seven foodborne pathogens. And later this year, the World Health Organization will publish eagerly anticipated estimates of the global burden of foodborne disease, also in DALYs.

What a time to be alive.

Most of these efforts build on CDC’s 2011 estimates of foodborne illness incidence. Whether in dollars, DALYs, QALYs, or what-have-you, these burden of disease studies consider not only how many illnesses we expect to see each year, but also the severity of those diseases and the chronic sequelae that can result. These estimates enable us to line up foodborne disease with other public health concerns, and to directly compare the impacts of specific foodborne hazards to one another.

It can be a bit confusing to decipher the swirls of numbers across these studies, each built on different assumptions, methods, and data, but it’s fair to say that they are mostly in agreement about which foodborne bugs cause the greatest burden on public health. Salmonella, Toxoplasma, Listeria, Campylobacter, and Norovirus have the highest estimated disease burden in the U.S. Other foodborne hazards that rank highly include E. coli O157, C. perfringens, ciguatoxin, and Vibrio species.

At this point, there’s nothing surprising about this list. We’ve had five years of hearing it, after all.

A few weeks ago, I gave a talk about all these estimates (slides here). I was feeling pretty good about how far we’ve come at getting a bead on the burden of foodborne disease, and how these estimates can help inform our priorities. Then I read this new commentary published in the Journal of Public Health Policy: “How useful is ‘burden of disease’ to set public health priorities for infectious diseases?”

Now, a title like that is not going to be followed by an abstract that reads, “Like, totally useful, dude.”

The authors, Ruth Berkelman of Emory University and James LeDuc of the University of Texas, make a compelling case for why low burden of disease should not equate to low public health importance. Using examples like Nipah, Ebola, and MERS, they point out that the most effective time to act for some emerging zoonotic diseases is early. For example, they write:

“If longer chains of human transmission of Nipah begin to appear, a vaccine and effective treatment would be critical. Arguments about its relatively low current burden of disease are unconvincing when the threat of introduction into densely populated urban centers is large for Nipah and for a number of other emerging infectious diseases that have the potential for spread, domestically and internationally. That it takes a long time to develop a vaccine or effective therapeutic drug is reason to start now, before an emergency starts.”

The commentary isn’t directed at food safety, but it makes two good points. First, while disease burden estimates provide useful information, let’s not fool ourselves into thinking they are the only measures to consider. For example, pathogens that impact infants, pregnant women, or other vulnerable populations may warrant special attention, as might those with very high case fatality rates, regardless of the number of annual cases.

Second, we should not only be ranking which problems are worst, but identifying which solutions are best. We should be asking which opportunities for intervention have the greatest public health bang for the buck?

I often make these same points when discussing burden of disease, but sometimes I forget, perhaps because I’m too easily lost in the analytical weeds, or too entranced by the shiny new numbers sorted from big to small. And so they bear repeating.

US: Economic burden of major foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States

13.may.15

United States Department of Agriculture

Sandra Hoffmann, Bryan Maculloch, and Michael Batz

http://www.ers.usda.gov/media/1837786/eib140_summary.pdf

What Is the Issue?

Each year, one in six people in the United States is sickened by a foodborne illness. Government, industry, and others expend considerable resources in trying to prevent these foodborne illnesses. To best marshall these resources, food industry managers and policy- makers need to know both the value of these efforts to society and how to target use of these resources. Estimates of the economic burden of illness provide a conservative measure of how much people are willing to pay to prevent these illnesses. This report provides an overview of recent estimates of the economic burden imposed annually by 15 leading foodborne pathogens in the United States. It also provides individual pathogen “pamphlets” that include:

Each year, one in six people in the United States is sickened by a foodborne illness. Government, industry, and others expend considerable resources in trying to prevent these foodborne illnesses. To best marshall these resources, food industry managers and policy- makers need to know both the value of these efforts to society and how to target use of these resources. Estimates of the economic burden of illness provide a conservative measure of how much people are willing to pay to prevent these illnesses. This report provides an overview of recent estimates of the economic burden imposed annually by 15 leading foodborne pathogens in the United States. It also provides individual pathogen “pamphlets” that include:

- a description of the course of illness that can follow an infection with the pathogen;

- a summary of information about the pathogen’s annual foodborne illness incidence and economic burden relative to other foodborne pathogens;

- a disease-outcome tree showing how many people experience different outcomes from food- borne exposure to the pathogen in the United States each year; and

- a pie chart showing the annual economic burden associated with different health outcomes resulting from infection with the pathogen.

What Did the Study Find?

Foodborne pathogens impose over $15.5 billion (2013 dollars) in economic burden on the U.S. public each year. Just five pathogens cause 90 percent of this burden. Estimates of economic burden per case vary greatly, ranging from $202 for Cyclospora cayetanensis to $3.3 million for Vibrio vulnificus.

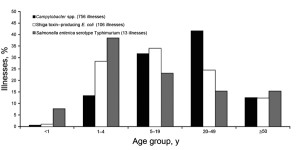

- Fifteen pathogens cause 95 percent or more of the foodborne illnesses, hospitalizations, and deaths in the United States for which a specific pathogen cause can be identified. They are Campylobacter spp., Clostridium perfringens, Cryptosporidium spp., Cyclospora cayeta- nensis, Listeria monocytogenes, Norovirus, Salmonella non-typhoidal species, Shigella spp., STEC O157, STEC non-O157, Toxoplasma gondii, Vibrio vulnificus, Vibrio parahaemo- lyticus, Vibrio other non-cholera species, and Yersinia enterocolitica.

- Eighty-four percent of the economic burden from these 15 pathogens is due to deaths. This reflects both the importance the public places on preventing deaths and the fact that the measure of economic burden used for nonfatal illnesses (medical costs + productivity loss) is a conservative measure of willingness to pay to prevent nonfatal illness.

- Pathogens’ rankings by total economic burden generally follow their rankings by economic burden due to pathogen-related deaths, with notable exceptions. Campylobacter causes slightly more deaths per year than Norovirus, yet because of the very large number of nonfatal cases caused by Norovirus, its economic burden is higher than that of Campylobacter. The high medical costs and productivity losses caused by Clostridium perfringens contribute to its total economic burden exceeding those of three other pathogens with higher economic burden due to deaths (Vibrio vulnificus, Yersinia enterocolitica, and STEC O157).

- Estimates of the incidence of foodborne disease acquired in the United States, and therefore economic burden estimates, are very uncertain. The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimates that the foodborne disease incidence from these 15 pathogens could range from 4.6 million to 15.5 million cases in a typical year. Based on this range of incidence estimates, economic burden could range from $4.8 billion to $36.6 billion (2013 dollars).

How Was the Study Conducted?

This report provides estimates of the costs of foodborne illnesses based on recently published journal articles. The estimates from that research, updated for inflation and income growth to 2013 values, are available in ERS’s Cost-of-Illness Estimates for Major Foodborne Illnesses in the U.S. data product at http://www.ers.usda. gov/data-products/cost-estimates-of-foodborne-illnesses.aspx.

This report summarizes the findings from the ERS data product and provides additional educational materials based on the data product and journal articles targeted to a broad audience. The data product website allows users to explore the sensitivity of economic burden estimates to modelling assumptions. The data product also provides the information needed to update estimates for inflation and income growth over time.

The estimates underlying this report extend and update prior ERS cost-of-illness estimates by adding 11 patho- gens and updating cost estimates for 4 other pathogens. These new estimates combine a cost-of-illness measure of economic burden for nonfatal illnesses and a willingness-to-pay measure for deaths. The estimates for new pathogens are based on a synthesis of data sources, including National Inpatient Sample data on hospitalization costs, and existing scientific literature. Estimates for all pathogens use 2011 CDC estimates of the incidence of foodborne illnesses acquired in the United States and associated hospitalizations and deaths. In modeling the likelihood of other health outcomes, the estimates rely on FoodNet data and reviews of scientific literature. In modeling the duration of illnesses and severity of health outcomes, the estimates rely on a review of clinical medical literature.