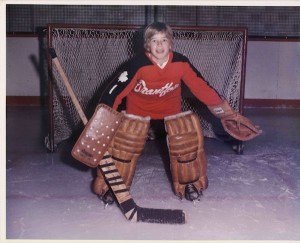

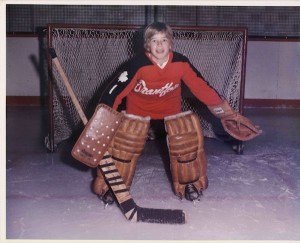

I’ve been playing, coaching, and even sometimes administering hockey – the ice kind – for almost 50 years.

I’ve seen every kind of parent, and as I age, I just pay attention to the kids, and tell the parents, get away from my bench.

I’ve seen every kind of parent, and as I age, I just pay attention to the kids, and tell the parents, get away from my bench.

So it’s not surprising that my volunteer gig as a food safety helper at the kid’s school didn’t end well.

It was, however, like the time Chapman worked in a restaurant for a month, educational.

Australia has an on-going outbreak of hepatitis A that has sickened at least 34, linked to frozen imported berries.

Europe has had tens-of-thousands-sickened in a different outbreak, and why I now always boil my frozen berries.

When the Australian outbreak hit the news, the person who runs the tuck shop wrote in the school newsletter they “would never use frozen berries.”

This is a common conceit I hear from Brisbane-types, which is convenient living in a sub-tropical climate.

So I wrote to the tuck shop person thingy and said, your unequivocal declaration goes against 150 years of freezing technology, that not everyone lives in a sub-tropical climate (Ontario? Canada?) and that the berries could be safely handled if cooked.

She came back with some stuff about sustainability, and all I could see was every hockey parent who thought their kid was the next Wayne Gretzky.

I grew up with Gretzky.

Food Standards Australia New Zealand has completed a risk statement on hepatitis A virus and imported ready-to-eat (RTE) berries. This statement has been given to the Department of Agriculture which is the enforcement agency for imported food.

FSANZ uses an internationally recognized approach when assessing food safety risks which involves looking at:

the likelihood of a food safety issue occurring

the consequence of the food safety issue.

We also look at mitigating factors, e.g. is the product going to be cooked or practices and procedures that can mitigate risk further.

The risk statement concluded that, hepatitis A virus in RTE berries produced and handled under Good Agricultural Practices (GAP) and Good Hygienic Practices (GHP) is not a medium to high risk to public health.

Effective control strategies minimize contamination at the primary production and food processing points of the supply chain

Effective control strategies minimize contamination at the primary production and food processing points of the supply chain

Regulatory authorities across the world, including those where outbreaks linked to berries or other produce have occurred, agree that hepatitis A virus contamination is best managed through good quality agriculture and hygiene practices throughout the supply chain.

Guidance is widely available on the good agriculture practices and good hygienic practices that focuses on preventing fresh produce becoming contaminated with viruses such as hepatitis A virus. For example, controls over the quality of water and fertilizers used in the field, as well as the hygiene of workers throughout the supply chain.

While there have been outbreaks associated with hepatitis A in ready-to-eat berries, they are infrequent internationally and rare in Australia

Over the last 25 years, there have been six reported outbreaks of hepatitis A associated with eating ready-to-eat berries around the world. A few of these were in Europe (involving mixed berries and strawberries grown and packed in Europe) and one was in New Zealand (involving domestically grown raw blueberries).

While one of these outbreaks was very large, when taken in the context of the amount of berries sold and traded throughout the world and the amount of berries consumed, the frequency of outbreaks is extremely low.

Hepatitis A infection can be incapacitating but it is not usually life-threatening and long-term effects are rare

Not all people exposed to the hepatitis A virus actually get sick. People who become infected might never show any symptoms. Unlike other foodborne illness, it is rare for small children to present with any symptoms. Long-term effects of having the virus are extremely rare and full recovery usually occurs in a number of weeks.

Because of the difficulties in detecting hepatitis A virus in food, there is very little data on level of contamination of ready-to-eat berries, but the evidence that is available suggests it’s very low.

Data on hepatitis A virus contamination are limited, partly because it is very difficult to test for the virus in food. But the data that is available from testing following outbreaks and the incidence of outbreaks themselves suggest contamination is rare.

There are no internationally agreed criteria for testing of berry fruits for the presence of hepatitis A virus.

Testing for E. coli can be used as an indicator of hygienic production. However, the presence of E.coli does not necessarily mean a food is unsafe and it is not a reliable test for the presence or absence of hepatitis A virus.

Hepatitis A virus cannot reproduce (increase in numbers) in RTE berries

Unlike some microorganisms like bacteria, hepatitis A virus doesn’t grow in food, so levels won’t increase during processing, transport and storage.

Many of the foods considered medium to high risk are foods that are associated with the kinds of microorganisms that can quickly multiply in food. These microorganisms are common and known to be responsible for a high number of outbreaks.

What does this advice mean for importers of ready-to-eat berries?

The Department of Agriculture has issued an Imported Food Notice in response to FSANZ’s advice.

What this means is that from 19 May 2015 importers of berries from any country must be able to demonstrate the product has been sourced from a farm using good agricultural practices.

In addition, good hygienic practices must be evident throughout the supply chain.

If not, then the berries could be considered to pose a potential risk to human health.

FSANZ has previously examined the issue of hepatitis A virus in produce following an outbreak in semi-dried tomatoes in 2010. Following that assessment, FSANZ determined that routine testing for viruses in food is of limited use because:

the virus in contaminated food is usually present at such low levels the pathogen can’t be detected by available analytical methods

viruses can be unevenly distributed and a result can be negative but food can still be unsafe

a positive result can come from the presence of genomic material from inactive or non-infectious virus in the food, but this doesn’t mean the virus is active.

What’s happening with the recalled berries?

In February 2015 FSANZ provided preliminary advice to the Department of Agriculture on the frozen berries linked to the outbreak.

FSANZ advised the department that current epidemiological evidence and some uncertainty about food safety controls implemented by the supplier of the berries indicates the product is a medium risk to public health until further information becomes available.

Patties Foods has told regulators about the company’s testing regime for the products in question including:

ground water testing on the field (for microorganisms, salt and chemicals)

pesticide testing on the field

pesticide and micro testing in the factory (including for E.coli, Salmonella and Listeria)

heavy metal testing in the factory

Further tests including microbiological tests were conducted pre-shipment and post shipment (after the product arrived in Australia).

Patties has initiated a more stringent testing program and has commenced an extensive testing program for the presence of hepatitis A virus in affected product.

What is being done to ensure all recalled product is off the shelves?

In Australia, state and territory regulatory authorities are responsible for working with the manufacturer or producer to ensure stock is removed from shelves.

Victorian authorities who are managing this recall are also conducting testing on affected product.

How do we know no other berry products are affected?

Patties Foods has informed FSANZ that the factory involved in processing the berries does not supply products to any customers other than Patties.

Is it true that a hepatitis A outbreak is more serious than other foodborne illness?

No. Foodborne illness as a result of bacteria such as Listeria, Salmonella and Campylobacter can be deadly, particularly for vulnerable populations.

There are an estimated 4.1 million cases of foodborne illness each year in Australia.

The latest report on foodborne illness estimates that each year there are more than 31,000 hospitalisations due to foodborne illness and 86 deaths.

Four pathogens (norovirus, pathogenic Escherichia coli, Campylobacter and nontyphoidal Salmonella species) are responsible for 93 per cent of the cases where the pathogens were known.

Up until the end of April, 2015 there have been 97 cases of hepatitis A this year in Australia (including the 34 cases linked to RTE frozen berries). At the same time last year there were 105 cases. Nearly half of all cases of hepatitis A reported in Australia are usually from people returning from overseas travel.

Up until the end of April, 2015 there have been 97 cases of hepatitis A this year in Australia (including the 34 cases linked to RTE frozen berries). At the same time last year there were 105 cases. Nearly half of all cases of hepatitis A reported in Australia are usually from people returning from overseas travel.

And my new grandson turned six-days-old. Maybe he’ll be a hockey player, maybe a risk assessor, maybe something else.

Ryan Asherin, previously a Surveillance Officer and Principal Investigator at the OHA,

Ryan Asherin, previously a Surveillance Officer and Principal Investigator at the OHA,