Ron Doering, counsel in the Ottawa offices of Gowlings, and a past president of the Canadian Food Inspection Agency, writes in his monthly Food in Canada column:

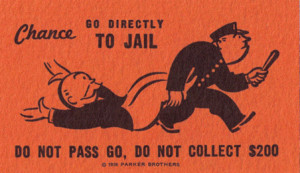

After warrants were issued for their arrest, the two food company executives turned themselves in to the police and then they were led into the court for their arraignment in shackles.

After warrants were issued for their arrest, the two food company executives turned themselves in to the police and then they were led into the court for their arraignment in shackles.

The Jensen brothers faced a possible six years in jail for the misdemeanor of failing to ensure the quality and safety of the food product they were selling. They did not go to jail primarily because they pled guilty. Last January they were sentenced to six months home detention and five years probation, and ordered to pay $150,000 in restitution.

The evidence was clear: neither of the corporate executives had any idea that their food product was adulterated or that they had done anything wrong. What’s going on here?

In this and several other recent cases, the United States Department of Justice has made it clear that it has adopted a new enforcement policy to aggressively use criminal prosecution against food company executives. Citing the serious public health consequences of foodborne illness, with 48 million Americans sickened every year and an estimated 3,000 deaths, Assistant Attorney General Stuart Delery has publicly warned corporate officers that they were now going to be held personally and criminally responsible if their companies failed to adequately control the quality of their food products. Delery has emphasized that introducing adulterated food into interstate commerce is a strict liability offence, meaning a company violates the law when it distributes an adulterated food whether or not it intended to do so.

In adopting this new aggressive policy the prosecutors have resurrected the old and mostly dormant 1975 U.S. Supreme Court decision in United States v Park, which held that corporate executives could be prosecuted criminally even for unintended violations of food laws by their companies. “This apparent revival of the Park Doctrine is a huge concern for the industry” asserts U.S. food law attorneys McGuireWoods.

This dramatic change in U.S. food law is evident in many recent cases. For example, in 2014 Iowa egg company executives pled guilty in a deal that included prison time and millions of dollars in fines after an outbreak that had sickened almost 2,000 people in 2010. In May 2015, arising from a tainted peanut butter recall in 2006, prosecutors extracted a settlement with the food giant ConAgra Foods that included a fine of $11.2 million, the highest criminal fine in U.S. food safety history.

This rising threat of criminal prosecution for food industry executives is real and has not gone unnoticed by food companies and their lawyers. Washington lawyer Gary Jay Kushner, a partner with Hogan Lovells and one of America’s leading food law lawyers, told me recently that “this is a serious development for food company executives. We’re seeing this increasing trend in a lot of cases.”

The most recent case that has garnered so much media attention involves the Peanut Corporation of America (PCA) in which an investigation revealed that its adulterated product had led to over 700 reported infections and at least nine deaths. After a six-week trial, a federal jury found PCA president Stewart Parnell and two other company executives guilty of violating several food safety laws and obstruction of justice. Because company employees falsified lab results and made several false and misleading statements to FDA investigators, prosecutors are seeking life sentences for PCA executives.

Criminal prosecution of company executives is not new in Canada. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency regularly brings charges in the criminal courts. What we haven’t seen yet in this country is major prosecutions of executives after recalls or prosecutors seeking jail terms for company executives who were unaware of any violation, though I know that this has been seriously considered in at least a couple of instances.

There is also another important distinction between Canada and the U.S. We have a longstanding, if narrowly defined, defence of due diligence in cases of strict liability offences; a defence that deserves to be better known, and the subject of next month’s column.