The UK Food Standards Agency (FSA) wants to balance consumer choice with public protection with its ‘risky foods framework’ policy for local authorities. John Bassett, food safety consultant, argues that this approach has implications for enforcers, industry and above all consumers.

Although the FSA went public on their risky foods framework at the end of last year, they haven’t been shouting about it too loudly. Steve Wearne, the FSA’s director of policy, emphasised that consumer choice was at the heart of everything they do and outlined the approach at the recent CIEH Food Safety Conference.

Although the FSA went public on their risky foods framework at the end of last year, they haven’t been shouting about it too loudly. Steve Wearne, the FSA’s director of policy, emphasised that consumer choice was at the heart of everything they do and outlined the approach at the recent CIEH Food Safety Conference.

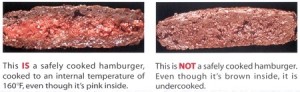

It is clear that the framework will support increased freedoms to sell and choose such ‘Russian roulette’ delicacies such as rare burgers and raw milk. Some consumers are passionate about their right to eat foods that many would consider unsafe, and cynics may say that the framework has been developed as a result of the inability of the FSA and local authorities to effectively communicate or regulate for those risks. A recent example of this is demonstrated by the court ruling allowing for Davy’s to sell rare burgers.

But apart from the strong UK consumer voice, there is a drive globally for regulators to base management decisions on risk and remove prescriptive controls that seek to reduce risk down to an unachievable zero risk. Risk-based controls will allow businesses to manage risks more flexibly, on the basis of robust risk assessment, which should lead to innovations in food products and cost-savings, benefits that can flow to consumers both directly through better/cheaper products and indirectly through more targeted regulatory attention to the most significant risks. In particular, there are significant cost, nutritional and environmental benefits to be realised by the reduction of over-processing of many food products.

While government and food businesses can develop or commission risk assessments, these products by definition will still pose a higher risk than the majority of foods. The remaining risk will have been deemed by the FSA to be ‘acceptable’, at least to the consumers who accept the higher risk that they pose. But will consumers be able to understand the risks that they are taking? One key communication channel will undoubtedly be packaging labelling. The FSA board is considering the extension of raw milk labelling requirements for Northern Ireland and England in their meeting in July, but they also recognise that ‘it is difficult to demonstrate quantifiable public health benefits associated with enhanced labelling and consumer research carried out … provided variable view’.

While government and food businesses can develop or commission risk assessments, these products by definition will still pose a higher risk than the majority of foods. The remaining risk will have been deemed by the FSA to be ‘acceptable’, at least to the consumers who accept the higher risk that they pose. But will consumers be able to understand the risks that they are taking? One key communication channel will undoubtedly be packaging labelling. The FSA board is considering the extension of raw milk labelling requirements for Northern Ireland and England in their meeting in July, but they also recognise that ‘it is difficult to demonstrate quantifiable public health benefits associated with enhanced labelling and consumer research carried out … provided variable view’.

Warnings on menus where rare burgers are served are subject to the same uncertainties as raw milk labels. A key part of the risky foods framework and the FSA strategy in general is the engagement of consumers on the risks they personally find acceptable. A lot more work is required before the FSA and businesses can say with confidence that the risks they want to communicate are truly, effectively received and understood, and hence accepted by consumers.