Ken Gruen, a retired Philadelphia restaurant inspector (“sanitarian”) who advises food establishments at Philadelphia International Airport told the Philadelphia Inquirer, “If the bathroom is kept in good condition – it’s clean, there is soap, there are paper towels, there is not a lot of litter on the floor – probably the kitchen is the same.”

Other signs of general sloppiness, health, and hygiene could be indicators as well. Is the knife used to slice limes at the bar left on the counter without cleaning? Has the buffet been ignored for hours? If the kitchen is visible, are workers wearing gloves? Is your waiter a mess?

More specific measures, like storing cheese at temperatures that are too cold for dangerous microbes, are noted in official inspection reports – if you have the patience and knowledge to interpret them.

To make them easier to understand – there are hundreds of potential code violations – all restaurants in New Jersey must display overall findings as “Satisfactory,” “Conditionally Satisfactory,” or “Unsatisfactory,” although the sign may not be visible from outside. Some cities (Toronto, Pittsburgh) post green, yellow, or red placards in the window. Another handful (New York, Los Angeles, San Francisco) put up consumer-friendly A-B-C letter grades.

Philadelphia does none of the above.

Philadelphia does none of the above.

No scoring system “has been found to be effective for food safety,” said Palak Raval-Nelson, who oversees inspections of nearly 12,000 food establishments for the Philadelphia Department of Public Health.

In fact, there is limited evidence that inspections themselves protect against foodborne illness. They are a snapshot in time: Only a stroke of luck would have the sanitarian present at the exact moment that a refrigerator malfunctions or a cook shows up sick.

But they may work in a different way.

“No one wants to be embarrassed,” said Doug Powell, a food-safety consultant in Australia and anchor of barfblog. “So inspections and disclosure systems make [restaurateurs] try harder. And it also contributes to the public conversation about food safety.”

Food-safety laws are written and enforced almost entirely at the state and local levels. Since the late 1990s, most jurisdictions, including Philadelphia, have adopted U.S. Food and Drug Administration recommendations that for the first time are based on the science of disease transmission. Cooking to a temperature high enough to kill microorganisms is a high-priority item; ceilings with missing tiles is low.

“It is really hard, I think, for a consumer to make very much sense of these detailed reports,” said food-safety specialist Craig Hedberg, a professor in the University of Minnesota’s School of Public Health.

But Hedberg doesn’t think inspections prevent much sickness anyway.

“We talk about food-borne illness like it’s a single thing,” Hedberg said. In reality, there are several kinds, each causing extremely uncomfortable (and sometimes dangerous) diarrhea and abdominal cramps, from one day to a week:

Between 10 percent and 20 percent of outbreaks are due to salmonella, increasingly carried on fresh produce that will be served without cooking. It’s not visible, and washing often fails to remove it.

Chopping and mixing quantities of, say, parsley or tomatoes, as most full-service restaurants must do, could spread the contamination through the entire batch, however. “The restaurant will simply be a pass-through,” Hedberg said. “The best they can do is try not to make the problem worse.”

And an inspection will not stop it.

Another 10 percent to 20 percent of outbreaks are traced to Clostridium perfringens. The bacteria grow and produce a toxin when spores germinate after cooking if foods are not cooled quickly enough before storage. It used to be more common, and has been successfully reduced through the priority that inspectors place on temperature control and cross-contamination, Hedberg said.

More than 50 percent of outbreaks in the United States are norovirus. It is spread when infected workers handle salads and serve sandwiches. Frequent hand washing helps, but ill employees simply should not show up for work. “Workers can come in sick a few hours a year,” Hedberg said, enough to start an outbreak but unlikely to be spotted during an inspection.

So what would work?

For a 2006 paper in the Journal of Food Protection, Hedberg led a team that compared various characteristics of 22 restaurants that had experienced outbreaks of food-borne illness and 347 that had not. The main difference was the presence of a certified kitchen manager – someone who has the power to change attitudes and atmosphere. These managers are regular kitchen employees or supervisors who have received additional training in food safety. They can spot and respond to risks, like sending home workers with symptoms of norovirus.

For a 2006 paper in the Journal of Food Protection, Hedberg led a team that compared various characteristics of 22 restaurants that had experienced outbreaks of food-borne illness and 347 that had not. The main difference was the presence of a certified kitchen manager – someone who has the power to change attitudes and atmosphere. These managers are regular kitchen employees or supervisors who have received additional training in food safety. They can spot and respond to risks, like sending home workers with symptoms of norovirus.

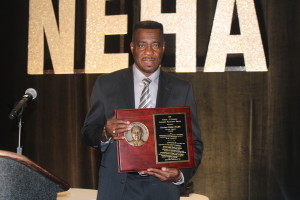

Toronto’s DineSafe program began in 2001. The most critical violations are noted in simple language on a green, yellow, or red sign posted out front. Ninety-two percent of restaurants get a “green” on their first inspection, said Sylvanus Thompson (above, left, pretty much as shown), associate director of Toronto Public Health. Polls show the program is overwhelmingly popular.