I don’t care who does meat inspection, as long as the results are available for public scrutiny, preferably at retail. As we have documented, there are problems with government inspections, audits, and no inspections (see below).

Ted Genoways, the author of “The Chain: Farm, Factory, and the Fate of Our Food,” asks in The New York Times, if, thanks to an experimental inspection program, a meatpacking firm produces as much as two tons a day of pork contaminated by fecal matter, urine, bile, hair, intestinal contents or diseased tissue, should that count as a success?

Ted Genoways, the author of “The Chain: Farm, Factory, and the Fate of Our Food,” asks in The New York Times, if, thanks to an experimental inspection program, a meatpacking firm produces as much as two tons a day of pork contaminated by fecal matter, urine, bile, hair, intestinal contents or diseased tissue, should that count as a success?

The agency responsible for enforcing food safety laws has not only approved this new inspection regime but is considering whether to roll it out across the pork-processing industry. Last month, the Food Safety and Inspection Service of the United States Department of Agriculture said it wished to see if the pilot program “could be applied to additional establishments.”

The issue was not whether microbiological testing was superior to physical inspection, officials said, but whether self-regulation was sufficient and safe. But in 1997, U.S.D.A. executives approved testing in five pork-processing plants.

By the time the pilot program was fully implemented, in 2004, Hormel Foods Corporation, a Fortune 500 company with headquarters in Austin, Minn., had succeeded in getting its two major slaughter operations included, and had acquired a third. The new inspection system allowed Hormel to increase the speed of its cut lines, just before demand for cheap pork products like Spam soared during the recession. My reporting revealed that Hormel went from processing about 7,000 hogs per shift to as many as 11,000.

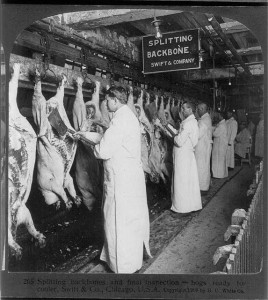

But some of Hormel’s own quality-assurance auditors began to raise concerns. Under normal U.S.D.A. guidelines, inspectors manually check the glands in the head of every hog, palpate the lymph nodes to check for tuberculosis nodules, feel the intestines for parasites and the kidneys for signs of inflammation or hidden masses. A former process-control auditor from the Austin plant told me that, by 2006, the line was running so fast that he doubted the lone U.S.D.A. inspector could do more than visual checks.

Then, last year, the U.S.D.A. inspector general reported on the hazard analysis project. The findings were damning. Enforcement of food safety protocols was so lacking at the five plants participating that between 2008 and 2011, three of the five were among the 10 worst violators nationwide (of 616 pork processors).

Then, last year, the U.S.D.A. inspector general reported on the hazard analysis project. The findings were damning. Enforcement of food safety protocols was so lacking at the five plants participating that between 2008 and 2011, three of the five were among the 10 worst violators nationwide (of 616 pork processors).

Philip Derfler, deputy administrator of the inspection service, promised a further investigation. That report was finally posted last month. Remarkably, it painted the new inspection program as a success — though much of its data suggested otherwise. From 2006 to 2010, for example, fecal contamination was consistently higher than in standard plants, often much higher.

In 2011, however, the program changed from allowing meat inspectors to decide which carcasses to inspect to a computerized system that set the sampling schedule and recorded results electronically. The system failed repeatedly that year, rendering all data unusable. Inspectors also reported failures in 2012 and 2013 that sent at least 100 million pounds of uninspected meat to market.

Despite this, in 2013, the rate of contamination recorded by the new computer system appeared low enough for the inspection service to declare victory. The new report said the number of serious violations was “exceedingly small.”

In fact, over the course of the study, contaminated carcasses were found in the experimental plants at a rate of about five to seven animals per 10,000 processed, with little variation over time. That may sound low, but given the volume of production and the weight of market hogs, it means that an operation the size of Hormel’s would “approve” about 4,000 pounds of contaminated pork a day.

The American public must be assured that high-volume production — and profits — have not been put before food safety.

Audits and inspections are never enough: A critique to enhance food safety

30.aug.12

Food Control

D.A. Powell, S. Erdozain, C. Dodd, R. Costa, K. Morley, B.J. Chapman

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0956713512004409?v=s5

Abstract

Internal and external food safety audits are conducted to assess the safety and quality of food including on-farm production, manufacturing practices, sanitation, and hygiene. Some auditors are direct stakeholders that are employed by food establishments to conduct internal audits, while other auditors may represent the interests of a second-party purchaser or a third-party auditing agency.

Some buyers conduct their own audits or additional testing, while some buyers trust the results of third-party audits or inspections. Third-party auditors, however, use various food safety audit standards and most do not have a vested interest in the products being sold. Audits are conducted under a proprietary standard, while food safety inspections are generally conducted within a legal framework.

There have been many foodborne illness outbreaks linked to food processors that have passed third-party audits and inspections, raising questions about the utility of both. Supporters argue third-party audits are a way to ensure food safety in an era of dwindling economic resources. Critics contend that while external audits and inspections can be a valuable tool to help ensure safe food, such activities represent only a snapshot in time.

This paper identifies limitations of food safety inspections and audits and provides recommendations for strengthening the system, based on developing a strong food safety culture, including risk-based verification steps, throughout the food safety system.