I confess. I experimented with something else while a university undergraduate: unpasteurized apple cider.

The ex and I would go to the Guelph Farmer’s Market and stock up, including unpasteurized cider.

The ex and I would go to the Guelph Farmer’s Market and stock up, including unpasteurized cider.

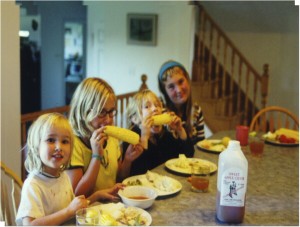

After moving to Kitchener (that’s in Ontario, Canada), we would bike with the kids out to the St. Jacobs Farmers’ Market in Waterloo, Ontario (that’s also in Canada) on Saturday mornings, buy some local wares, including cider, although we preferred the Waterloo County Farmer’s Market across the street.

By the time we moved back to Guelph in 1997, I’d finished my PhD in food science, and had become exceedingly wary of unpasteurized cider.

So had the U.S. government.

In October, 1996, 16-month-old Anna Gimmestad of Denver drank Smoothie juice manufactured by Odwalla Inc. of Half Moon Bay, Calif. She died several weeks later; 64 others became ill in several western U.S. states and British Columbia after drinking the same juices, which contained unpasteurized apple cider –and E. coli O157:H7. Investigators believe that some of the apples used to make the cider may have been insufficiently washed after falling to the ground and coming into contact with deer feces.

By 1997, one of my first students was working with a cider producer at the Guelph market, who had gone so far as to set up his own microbiology lab at his farm.

In the fall of 1998, I accompanied one of my then four daughters on a kindergarten trip to the farm. After petting the animals and touring the crops –I questioned the fresh manure on the strawberries –we were assured that all the food produced was natural. We then returned for unpasteurized apple cider. The host served the cider in a coffee urn, heated, so my concern about it being unpasteurized was abated. I asked: “Did you serve the cider heated because you heard about other outbreaks and were concerned about liability?” She responded, “No. The stuff starts to smell when it’s a few weeks old and heating removes the smell.”

Today, Chapman reported that the Canadian Food Inspection Agency noted an outbreak of E. coli O157 linked to unpasteurized cider sold at the St. Jacobs Farmers’ Market.

Why CFIA reports an outbreak but relies on Health Canada or the Public Health Agency of Canada to report actual illnesses is baffling. Guess it keeps the different bureaucrats busy.

Fortunately there are a handful of reporters still employed in Ontario, and one at the K-W Record says at least three people have been sickened with E. coli O157 from the unpasteurized cider.

Food safety inspectors are searching across southern Ontario for 2,000 litres of E. coli-contaminated apple cider that’s already made three people ill.

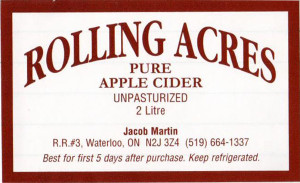

Some of the unpasteurized juice from Rolling Acres Cider Mill, 1235 Martin Creek Rd., near St. Jacobs, is in unmarked, 1.3-litre plastic bags.

A Waterloo health official suspects some of the perishable juice it is already stashed away in household freezers for use weeks or months later.

A Waterloo health official suspects some of the perishable juice it is already stashed away in household freezers for use weeks or months later.

Health officials are also tracking cider made for other retailers on Oct. 10, which is also likely contaminated with the bacteria that causes brutal stomach upset.

“The tracing is still ongoing,” said Chris Komorowski, food safety manager, at Waterloo Region public health.

Suspect cider pressed Oct. 10 at Rolling Acres has likely been sold as far east as Toronto and west of Waterloo, he said. “It’s all of southern Ontario.”

Rolling Acres is co-operating with the investigation, providing paperwork to track Oct. 10 batches of cider, Komorowski said. Waterloo and federal food inspectors have taken a close look at the apple press operation and found no problems.

“Currently they are meeting all regulatory food safety requirements from both agencies,” Komorowski said. “They’re in full compliance with that.”

The owner of Rolling Acres wasn’t available for comment.

Here’s the abstract from a paper Amber Luedtke and I published back in 2002:

A review of North American apple cider outbreaks caused by E. coli O157:H7 demonstrated that in the U.S., government officials, cider producers, interest groups and the public were actively involved in reforming and reducing the risk associated with unpasteurized apple cider. In Canada, media coverage was limited and government agencies inadequately managed and communicated relevant updates or new documents to the industry and the public.

Therefore, a survey was conducted with fifteen apple cider producers in Ontario, Canada, to gain a better understanding of production practices and information sources. Small, seasonal operations in Ontario produce approximately 20,000 litres of cider per year. Improper processing procedures were employed by some operators, including the use of unwashed apples and not using sanitizers or labeling products accurately.

Most did not pasteurize or have additional safety measures. Larger cider producers ran year-long, with some producing in excess of 500,000 litres of cider. Most sold to large retail stores and have implemented safety measures such as HACCP plans, cider testing and pasteurization. All producers surveyed received government information on an irregular basis, and the motivation to ensure safe, high-quality apple cider was influenced by financial stability along with consumer and market demand, rather than by government enforcement.