Campylobacter jejuni is the most common agent of food poisoning in industrialized nations. Professor Gary Dykes’ team at Monash University is trying to understand how it not only survives, but how it persists under conditions that should kill it.

The various species of Campylobacter – 18 have been described to date – are delicate organisms that colonize the intestines of livestock species and live harmlessly as members of their commensal gut flora. Dykes says they are very fastidious in their requirements for survival and growth.

The various species of Campylobacter – 18 have been described to date – are delicate organisms that colonize the intestines of livestock species and live harmlessly as members of their commensal gut flora. Dykes says they are very fastidious in their requirements for survival and growth.

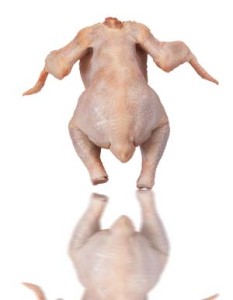

How, then, do they manage to survive and multiply outside the host animal’s body, despite the use of chemical and physical measures to prevent contamination as meat moves through the food-processing chain from the slaughterhouse to the kitchen?

In industrialized nations, Campylobacter food poisoning occurs at an annual rate of between 20 and 150 cases per 100,000 people. Most human infections involve C. jejuni, a commensal species in chickens that survives in raw and undercooked chicken.

Dykes and his colleagues at Monash University have been trying to determine how Campylobacter manages to attach and survive on exposed food processing surfaces and uncooked meat after animals are slaughtered. All this without succumbing to conditions that are unfavourable for them, such as the high levels of oxygen in air.

He says Campylobacter thrives in an environment that contains less than 5% oxygen – well below the natural 20.95% concentration in air.

Paradoxically, despite its preference for living in the warmth of the intestinal tract, Campylobacter struggles to survive at temperatures higher than 20° Celsius outside the body.

In a recent review paper – ‘Campylobacter and Biofilms’ – Dykes and Amy Huei Teen Teh, from Monash University’s Malaysian campus, reviewed research into the microbe’s ability to form biofilms.

They say that while some studies have shown that C. jejuni does form single-species biofilms on abiotic surfaces in the laboratory, not all strains do so, and some of the biofilms are in the form of aggregated cells, pellicles or flocs that are unlikely to occur on food-processing surfaces in poultry processing plants.

Moreover, most studies have been conducted under static conditions at very low oxygen levels, which do not represent real-world conditions in poultry processing plants.

Moreover, most studies have been conducted under static conditions at very low oxygen levels, which do not represent real-world conditions in poultry processing plants.

The few studies made of the microbes under flow conditions have failed to demonstrate that it can form monospecific biofilms under such conditions, and pre-formed monospecific biofilms do not persist at higher flow rates.

Dykes and Teh suggest the fragility of monospecific biofilms of C. jejuni means they are unlikely to be present in poultry plants, where the atmosphere is aerobic and the cells are exposed to high shear forces.

The persistence of the species through the poultry processing chain may thus rest on the species’ ability to form mixed biofilms with other species in the processing environment – studies have shown that such mixed-species biofilms can persist under higher flow conditions than monospecific biofilms of C. jejuni.

They concluded that it is important to understand the mechanisms that contribute to the formation of complex biofilms containing C. jejuni under real-world conditions in processing plants – particularly its interactions with other biofilm-forming species.