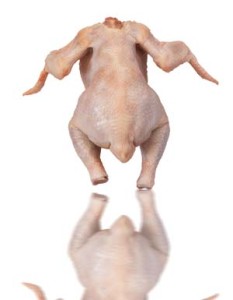

Canadian chicken farmers are putting an end to controversial egg injections, which provided the world with a “textbook” example of the perils of mass medication.

By injecting eggs at hatcheries with ceftiofur, a medically important antibiotic, the farmers triggered the rise of resistant microbes that showed up in both chickens and in Canadians creating a “major” public health concern.

The case – documented by federal and provincial sleuths who track microbes at farms, slaughterhouses and retail meat counters – is held up as powerful evidence of resistant superbugs moving from farm to fork.

The case – documented by federal and provincial sleuths who track microbes at farms, slaughterhouses and retail meat counters – is held up as powerful evidence of resistant superbugs moving from farm to fork.

“It is going to be in medical textbooks for as long as there are textbooks around,” says John Prescott, a professor with the Ontario Veterinary College at the University of Guelph.

On May 15 injecting eggs with ceftiofur will be banned as part of a new antibiotics policy adopted by Chicken Farmers of Canada, representing the 2,700 poultry farmers across the country.

“The industry has gone ahead and done this voluntarily, but it is not a voluntary program,” says Steve Leech, the association’s national programs manager. He says the ban is mandatory with penalties and fines for violators.

While the ban is better late than never, Prescott says government should have stopped the injections years ago.

Microbe trackers working with the Public Health Agency of Canada first reported in 2003 that they were picking up higher rates of ceftiofur resistance in Quebec. In 2004, they reported resistance was just as high in Ontario “in both humans and chicken.”

A strain of bacteria called Salmonella Heidelberg, that can cause food poisoning, had armed itself with the biochemical machinery needed to resist ceftiofur. Ceftiofur belongs to a class of antibiotics known as cephalosporins, which are often used on hard-to-cure infections in people.

The scientists soon linked the rise of the resistant Salmonella to chicken hatcheries that were injecting ceftiofur into eggs prophylactically to try prevent infections in chicks.

The scientists soon linked the rise of the resistant Salmonella to chicken hatcheries that were injecting ceftiofur into eggs prophylactically to try prevent infections in chicks.

The way Canadian hatcheries were allowed to keep using ceftiofur highlights the “inability” of Canadian health officials to stop inappropriate use of antibiotics, says Prescott.

“There was clear evidence of an adverse effect on public health,” he says, but dealing with the issue fell between the “gaps” in federal and provincial regulations.

Ceftiofur was never approved by Health Canada for use in chickens or eggs but hatcheries used it “extra-label,” which falls under the provincial jurisdiction.