Despite what some Canadian academics, government and industry types say about the safety of Canadian meat, the U.S thinks it sorta sucks.

This is nothing new.

But does matter to cattle ranchers who rely on trade with the U.S.

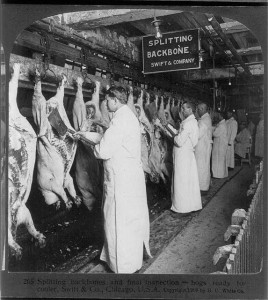

According to a report in the Globe and Mail, a U.S. audit of Canada’s food-safety system calls on the federal regulator to strengthen oversight of sanitation and the humane handling  of animals at meat-slaughtering plants.

of animals at meat-slaughtering plants.

The findings from the tour of seven food-processing facilities, two laboratories and five Canadian Food Inspection Agency offices in the fall of 2012 were kept confidential until recently.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture declined to release the report earlier to The Globe and Mail, which requested it through U.S. access to information law. The findings were published last month on the department’s website.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency received an “adequate” rating, the lowest of three scores that are meted out to countries deemed eligible to export food to the United States. The designation means Canada will be subject to more robust audits and its food exports will undergo more inspections at the U.S. border than those of countries whose food-safety systems were rated “average” or “well-performing.”

Canada’s food-safety system faced heightened scrutiny after 23 people died in an outbreak of listeriosis linked to a Maple Leaf Foods plant in Toronto in 2008, and E. coli contamination in 2012 at the former XL Foods facility near Brooks, Alta., led to the largest meat recall in Canadian history.

The federal government has revamped oversight of the CFIA, transferring responsibility to the Health Minister from the Agriculture Minister in October. The true effect of that change – whether it is substantial or cosmetic – remains unclear.

The U.S. review reveals that auditors found sanitation issues, including flaking paint and rust on pipes and overhead rails, at a pig-slaughter facility in Langley, B.C. Problems were also observed at the former XL cattle-slaughter plant, then temporarily shut down amid the E. coli outbreak in which 18 people fell sick with potentially deadly bacteria.

On their Nov. 2, 2012, visit to XL, auditors noted greasy spots on several conveyor belts in the boning room, which could have led to contamination. Among other issues observed was dust on protective trays under ventilators and blowers, also a contamination concern.

“There are always issues with audits, but overall, the audit findings were very good,” Tom Graham, director of CFIA’s domestic inspection division, said of the 2012 audit.

The CFIA plans to add extra oversight to its inspection program. The agency will establish a permanent inspection verification office in the spring, Mr. Graham said. The new office, which was recommended in an independent review of the XL contamination, will review inspection activities at food plants.

Keith Warriner, a food-science professor at the University of Guelph, thinks additional oversight of inspectors is a good idea. He said the XL recall and the listeriosis outbreak highlighted weaknesses.

“The common feature of those [cases] is that the CFIA weren’t applying the rules. They were turning a blind eye, and that was more so in the case of XL Foods,” Dr. Warriner said. “You need to have this [new] inspection service to make sure the inspectors are applying the regulations.”