During a visit to a large, international city, I was hanging out with a public health type, who pointed out some row housing visible from the building we were in, and each one seemed to have a decent-sized garden. He said those gardens supply a lot of the produce to the high-end restaurants in the city. And they all use night soil.

Human poop.

Eliza Barclay of NPR reports that any gardener will tell you that compost is “black gold,” essential to cultivating vigorous, flavorful crops (why do they write with dick  fingers?).

fingers?).

Barclay was excited the U.S. Composting Council was connecting community gardeners with free material from local facilities through its Million Tomato Compost Campaign.

I signed us up last month, and was promptly contacted by Clara Mills, the environmental coordinator for Spotsylvania County in central Virginia. Mills volunteered to deliver a dump truck full of compost to our garden from her facility, an hour away. It sounded too good to be true. Then one of my fellow gardeners noticed the source of the Spotsylvania compost: biosolids, or human poop that’s been treated and transformed into organic fertilizer.

About 50 percent of the biosolids produced in the U.S. are returned to farmland through a process that is heavily regulated by the Environmental Protection Agency. Even so, some people – including the Sierra Club — remain skeptical of the use of this waste product in food production. They worry that heavy metals, pathogens or pharmaceuticals might survive the treatment process and contaminate crops. So what’s an urban gardener to do in light of mixed perceptions about whether it’s OK to use poop to grow your food?

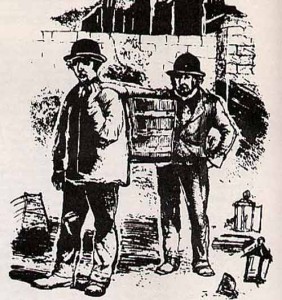

First, remember that for thousands of years, before the invention of synthetic fertilizer in 1913, many farmers utilized their decomposed sewage, sometimes called “night soil,” to replenish the soil with nutrients lost in farming. The Chinese were especially adept at using human waste this way – one historical account notes that in 1908, a contractor paid the city of Shanghai $31,000 in gold for the privilege of collecting 78,000 tons of human waste and carting it off to spread on fields.

When growing cities required that sewage be piped outside of the city, the practice dropped off and attention turned to improve wastewater treatment to avoid polluting waterways. Raw waste is, of course, nasty stuff, and only useful after all the dangerous bacteria have been killed off, either by heat or anaerobic digestion.

But the sludge was still piling up in landfills, so scientists began testing how to use it in agriculture safely; the waste was a free source of nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus, afterall. And letting it sit in landfills or incinerating it created its own  environmental issues. By the 1990s, the Environmental Protection Agency created strict standards with two tiers for biosolids still in use today. To sell Class A biosolids to farmers and gardeners, facilities have to ensure that there are no dangerous heavy metals or bacteria in the end product.

environmental issues. By the 1990s, the Environmental Protection Agency created strict standards with two tiers for biosolids still in use today. To sell Class A biosolids to farmers and gardeners, facilities have to ensure that there are no dangerous heavy metals or bacteria in the end product.

The ick factor, however, has not faded entirely.

Bowing to public feedback, the U.S. Department of Agriculture decided in 2000 to prohibit the use of sludge in the National Organic Program. This was in spite of the fact that “there is no current scientific evidence that use of sewage sludge in the production of foods presents unacceptable risks to the environment or human health,” USDA spokesman Samuel Jones tells The Salt.

A handful of activists have also sounded the alarm on the widespread use of biosolids in conventional agriculture. They allege, among other things, that the EPA-approved treatment of biosolids doesn’t address all the possible contaminants in the waste.

Maybe, but I’d rather have poop treated using science than some backyard night soil.