There’s plenty of talk amongst policy wonks about various food safety reforms, but that’s been going on for years: people eat three times a day.

Erin Brodwin writes in Scientific American that consumers look for safer food, especially as the public becomes more aware of

bacterial outbreaks, and farms in the past seven years have led the charge to respond.

bacterial outbreaks, and farms in the past seven years have led the charge to respond.

At least 15 years in my direct experience.

Consumers have begun to demand safer products via their collective buying power, says Greg West, president and CEO of National Pasteurized Eggs in Lansing, Ill. West’s company, which produces pasteurized eggs in an effort to eliminate Salmonella, has seen consumer demand for its product double in the past year. And West is more than happy to supply the safer eggs—sales, he said, have skyrocketed since the Salmonella outbreaks in the 1990s and a more recent flare-up in 2006 that made national headlines.

Preventing bacterial outbreaks is a matter of reducing risk, West says. Some cases of Salmonella-related illness, he notes, could have been prevented simply by cooking them thoroughly. Unfortunately, many people don’t cook eggs completely; over-easy, poached and soft-boiled eggs are all bacterial vectors. “Why not stop the risk before it enters the supply chain?” he says. All of the company’s eggs go through a hot-water pasteurization bath. Afterward, each egg is sealed with a wax coating to prevent potential future contamination and stamped with a red circle “P” to denote that they have been pasteurized.

Other companies, however, can’t bathe their products in bacteria-killing solution as a matter of practicality. Earthbound Farm in San Juan Bautista, Calif., which lost $70 million as a result of an E. coli outbreak in its fresh spinach in 2006, began a massive safety overhaul in 2006 that incorporated vigorous bacterial testing with innovative safety methods such as UV radiation. “At the end of the day you can’t rely on government or academia,” says Earthbound Farm head of food safety, Will Daniels. “You have to have relationships with the suppliers and know the process.”

The California Strawberry Commission has made products safer not by implementing new technologies, rather they better educate farmers, says Andrew Kramer, director of grower education. Strawberries are harvested year-round, so the field is continually replete with workers; as a labor-intensive crop, strawberries mandated a people-centered approach to safety.

For example, when the company discovered that workers were taking breaks in the field rather than in designated areas to the side of the crops, it also found that food trash residue was diminishing crop quality and attracting animals to growing areas. Kramer’s team found that animals and bacteria attracted to scraps would often invade crops as well. Commission experts soon realized that gaps in communication between commissioners, growers and farmers were to blame—growers

were not telling farmers about break protocol, and some weren’t even supplying chairs in dedicated eating locations. So commission experts began a series of training and education workshops in English and Spanish, and instructed growers to provide workers with portable chairs at a central location, preventing food scraps from attracting bacteria to crop sites. To tackle other field safety issues, directors of the grower education program came up with a food safety flip chart—a giant wooden how-to manual complete with diagrams and illustrations on field safety (the 4-foot one we came up with over 10 years ago and hung in a high traffic area in greenhouses is above, left). Farm safety educators use the chart during trainings, during which they instruct workers on everything from correct hand-washing practices how to identify a diseased crop before it infects the whole field.

were not telling farmers about break protocol, and some weren’t even supplying chairs in dedicated eating locations. So commission experts began a series of training and education workshops in English and Spanish, and instructed growers to provide workers with portable chairs at a central location, preventing food scraps from attracting bacteria to crop sites. To tackle other field safety issues, directors of the grower education program came up with a food safety flip chart—a giant wooden how-to manual complete with diagrams and illustrations on field safety (the 4-foot one we came up with over 10 years ago and hung in a high traffic area in greenhouses is above, left). Farm safety educators use the chart during trainings, during which they instruct workers on everything from correct hand-washing practices how to identify a diseased crop before it infects the whole field.

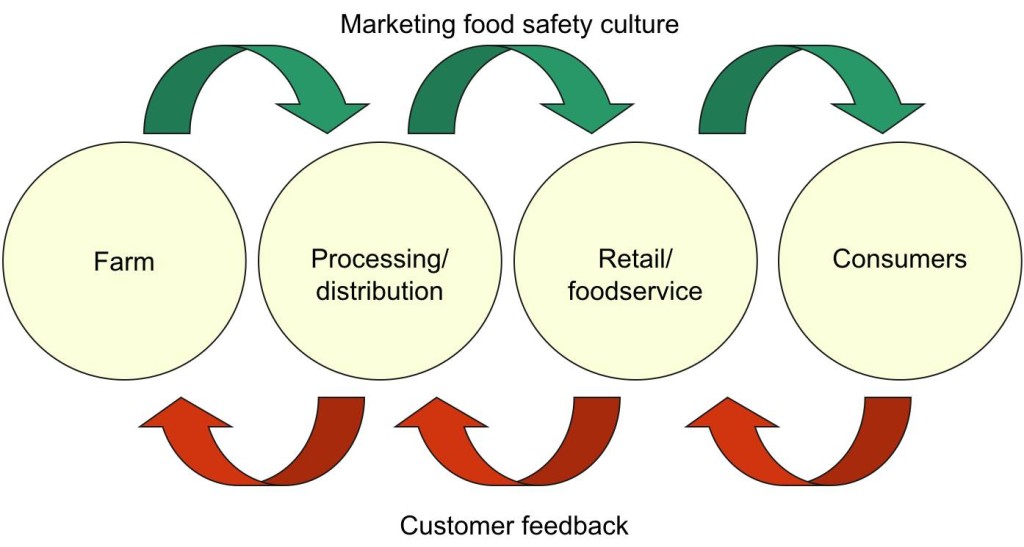

These examples have been well-known for decades. Those growers that take food safety seriously and can back it up with data should market their safety efforts at retail so consumers can choose.