Whenever I’m confused I watch TV. And then I reach for history.

A new examination by the U.S. Pharmacopeial Convention (USP), discovered rising numbers of fake ingredients in products from olive oil  to spices to fruit juice.

to spices to fruit juice.

“Food products are not always what they purport to be,” Markus Lipp, senior director for Food Standards for the independent lab in Maryland, told ABC News.

In a new database, USP warns consumers, the FDA and manufacturers that the amount of food fraud they found is up by 60 percent this year.

USP tells ABC News that liquids and ground foods in general are the easiest to tamper with:

Olive oil: often diluted with cheaper oils

Lemon juice: cheapened with water and sugar

Tea: diluted with fillers like lawn grass or fern leaves

Spices: like paprika or saffron adulterated with dangerous food colorings that mimic the colors

Milk, honey, coffee and syrup are also listed by the USP as being highly adulterated products.

Also high on the list: seafood. The number one fake being escolar, an oily fish that can cause stomach problems, being mislabeled as white tuna or albacore, frequently found on sushi menus.

National Consumers League did its own testing on lemon juice just this past year and found four different products labeled 100 percent lemon juice were far from pure.

And I now have the luxury of having my own lemon and Tahitian lime trees on my concrete balcony.

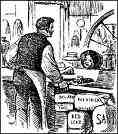

Food fraud is nothing new.

Historian Madeleine Ferrieres, until recently Professor of Modern History at the University of Avignon and the author of my favorite food  book, 2002’s Mad Cow, Sacred Cow, said in a recent interview, “we still live with the illusion of modernity, with the false idea that what happens to us is new and unbearable. These are not risks that have arisen, but our consumer behavior has changed.”

book, 2002’s Mad Cow, Sacred Cow, said in a recent interview, “we still live with the illusion of modernity, with the false idea that what happens to us is new and unbearable. These are not risks that have arisen, but our consumer behavior has changed.”

What’s new is better tools to detect fraud, which also presents an opportunity: those who use the real deal should be able to prove it through DNA testing and brag about it.

The days of faith-based food safety are coming to a protracted close.

As Ferrieres wrote in her book,

“All human beings before us questioned the contents of their plates. … And we are often too blinded by this amnesia to view our present food situation clearly. This amnesia is very convenient. It allows us to reinvent the past and construct a complaisant, retrospective mythology.”