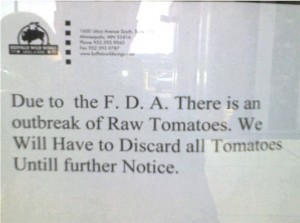

In 2008, U.S. tomato growers, wholesalers, and retailers in Florida lost an estimated $250 million when they could not sell their product after an investigation of a possible Salmonella spp., outbreak linked to their product resulting in a national health advisory. Consumer confidence in the safety of tomato products eroded, while food safety practices  on farms and throughout the supply chain were called into question. Other producers were also affected by this health advisory and found themselves answering questions about growing conditions, the safety of inputs (including water) handling and distribution of products.

on farms and throughout the supply chain were called into question. Other producers were also affected by this health advisory and found themselves answering questions about growing conditions, the safety of inputs (including water) handling and distribution of products.

That’s what Chapman told the Great Lakes Fruit, Vegetable and Farm Market Expo in December 2011, based on work he did along with Audrey Kreske and me, and which has now been revised and re-edited for The Grower, an Ontario-based trade publication.

Recent fresh produce-related outbreaks have created an environment where commodity groups and producers are even more concerned about managing the fallout after a foodborne incident.

Crisis management in the food industry has four phases:

• Prevention: Employing a good food safety culture, including staying current on risk factors.

• Preparation: Proactively planning for a problem and monitoring public discussion risk.

• Management: Implementing the plan using multiple messages and media.

• Recovery: Reassessing risk exposure and telling the story of changes.

Prevention

Food safety culture is how an organization or group approaches food safety risks, in thought and in behavior, and is a component of a larger organizational culture. Creating a culture of food safety requires application of the best science with the best management and communication systems. Firm owners and operators need to know the risks associated with their products and how to manage those risks. Having technical staff in place to stay abreast of emerging food safety risks and conduct ongoing evaluations of procedures, supplier requirements and front-line staff practices provides a necessary foundation for a good food safety culture.

Preparation

Crises will happen. Companies who understand this, and are prepared to deal with them will survive. Those who are not risk losing their market – and often do. While proactively managing microbiological risks, organizations with a strong culture of food safety also anticipate that outbreaks of foodborne illness may occur despite  the use of sound food safety systems. Industries strong in crisis management including, information sharing, monitoring and reactive crisis communication skills, can drastically reduce the impact of deleterious and harmful media if an outbreak arises (Jacob et al., 2011). Being prepared to speak openly speaking about risk reduction strategies and demonstrating risk management practices can reduce financial impacts and allow public trust to be regained quicker than if a firm/industry had not planned.

the use of sound food safety systems. Industries strong in crisis management including, information sharing, monitoring and reactive crisis communication skills, can drastically reduce the impact of deleterious and harmful media if an outbreak arises (Jacob et al., 2011). Being prepared to speak openly speaking about risk reduction strategies and demonstrating risk management practices can reduce financial impacts and allow public trust to be regained quicker than if a firm/industry had not planned.

Management

An increasing number of consumers seek food safety information from Internet sources, including one in eight Canadian consumers and one in four American consumers.

Following 2006 (E.coli O157 in spinach) and 2008 (Salmonella Saintpaul in Serrano peppers) news spread through the Internet in an unprecedented fashion. Producers, processors, retailers and regulators of agricultural commodities must now pay particular attention to evolving discussion and engage in the public discussion while the crisis is occurring. A firm or industry that is not forthcoming with information of who knew what, when, and what decisions were made sets itself up for loss of trust because media and Internet discussion goes towards these questions.

During a crisis it is necessary for a company or industry to talk about the science, discuss risks and tell an interested public about what is known, what is unknown and on what evidence decisions are made. Being available and understanding how media functions are also necessary skills for food industry members. Without recognizing deadlines or telling succinct stories of risk management, individuals risk the chance that others will fill the information vacuum with inaccurate information.

Recovery

A firm employing the best crisis management practices starts the recovery phase as soon as notification of a problem. Publicly, producers must address the problem, apologize to affected individuals; and, reach out to the media about risk-reduction changes. It is best to establish a dialogue with groups to demonstrate the organization’s openness and commitment to public safety and health. Internally a firm plans for reentry to the market, logistics and how new risk-management strategies will impact other business activities. If there was media attention around the crisis event, the one-year anniversary will often garner further coverage. An organization must be able to demonstrate that they have learned something/changed process in response and assess internally whether the same risks to public health exist by asking, “would we have the outbreak again today?”