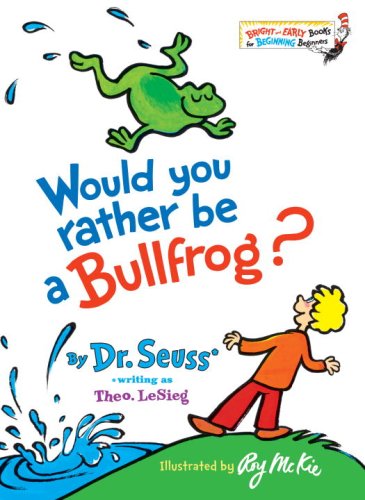

My kids love a Dr. Seuss book called Would You Rather Be a Bullfrog? The Cat in the Hat author provides a list of choices that are a bit weird — "would you rather be a ball, or would you rather be a bat?”.

Reporters often pose similar questions – where would you rather eat or where are pathogens more likely to be found: in organic food or conventionally grown; restaurants or home; and, increasingly, a supermarket chain or a farmers’ market.

While noble questions, I’m not sure they matter. With millions of meals served every day, the vast majority of food making it to plates doesn’t have pathogens. Solely using outbreaks to calculate risk isn’t the greatest strategy, as most illnesses are not reported, counted or linked to others; the absence of a recorded outbreak does not equate to a lack of risks.

A better question is where are risk factors more likely to be found — but unfortunately the data isn’t there.

Carol Guensberg of Scripps Howard News Services and I spoke a few times about farmers market food safety issues as she investigated whether farmers’ markets are riskier or less risky than other food outlets.

There are fewer controls over foods sold at markets than in bricks-and-mortar stores. And a bucolic venue doesn’t diminish the risk that trouble might lurk in those farm-fresh eggs, leafy greens and homemade pickles.

"We hear often that the food you get at the farmers market is so safe and better for you … because you’re looking into the eyes of the person who grew it or made it," said Vance Bybee, a food-safety expert with Oregon’s department of agriculture.

He’s learned that’s no guarantee.

Last summer, strawberries sold at farmers markets and roadside stands in northwest Oregon were contaminated with E. coli O157:H7, killing one woman and sickening 16 other people. Investigators traced the outbreak to deer feces at Jaquith Strawberry Farm in rural Washington County, Ore. Though the state requires such vendors to sell only foods they’ve produced, "we learned that some of those strawberries were purchased and resold four times before they made it to the actual consumer," Bybee said.

Few outbreaks have been directly linked to farmers markets. Yet experts say foodborne illness is underreported — especially when it involves food that isn’t consumed in one place at one time, as at restaurants or church suppers.

Most states have approved the home production of items that carry little risk of spoiling without refrigeration, such as preserves, candies, baked goods and dried fruits or tea blends. Some states’ laws are broader. Colorado passed a law in March that also allows the sale of less than 250 dozen eggs. And Wisconsin’s so-called "pickle bill," approved in 2010, lets home canners sell pickles, salsa and other acidified foods direct to customers. Such canned foods pose a threat if improperly prepared; they must be labeled as "made in a private home not subject to licensing or inspection," the law says. Many states require similar labeling, as well as training in safe food handling.

"The idea is if you’re a cottage producer, you produce very little food, so very few people are going to get sick. I’m not sure that’s how you want your safety system to operate," [David ]Plunkett [of Center For Science in the Public Interest] said. He repeated, with relish, what someone told him: "This is what’s known as faith-based food safety."

While Inspections, audits, written food safety plans, testing regimes and results all help paint a picture and convince shoppers that the folks in charge know what they are doing, almost all food safety is faith-based, at a farmers’ market or elsewhere.

As a shopper, I don’t care what size they are, where they are located or what their production style is – I only want to know whether the person making what I’m eating can manage food safety risks or not. And whether they do it all the time.