James Gorman of the New York Times writes that disgust is having its moment in the light as researchers find that it does more than cause that sick feeling in the stomach. It protects human beings from disease and parasites, and affects almost every aspect of human relations, from romance to politics.

In several new books and a steady stream of research papers, scientists are exploring the evolution of disgust and its role in attitudes toward food, sexuality and other people.

Paul Rozin, a psychologist who is an emeritus professor at the University of Pennsylvania and a pioneer of modern disgust research, began researching it with a few collaborators in the 1980s,  when disgust was far from the mainstream.

when disgust was far from the mainstream.

“It was always the other emotion,” he said. “Now it’s hot.”

Speaking last week from a conference on disgust in Germany, Valerie Curtis, a self-described “disgustologist” from the London School of Public Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, described her favorite emotion as “incredibly important.”

She continued: “It’s in our everyday life. It determines our hygiene behaviors. It determines how close we get to people. It determines who we’re going to kiss, who we’re going to mate with, who we’re going to sit next to. It determines the people that we shun, and that is something that we do a lot of.”

It begins early, she said: “Kids in the playground accuse other kids of having cooties. And it works, and people feel shame when disgust is turned on them.”

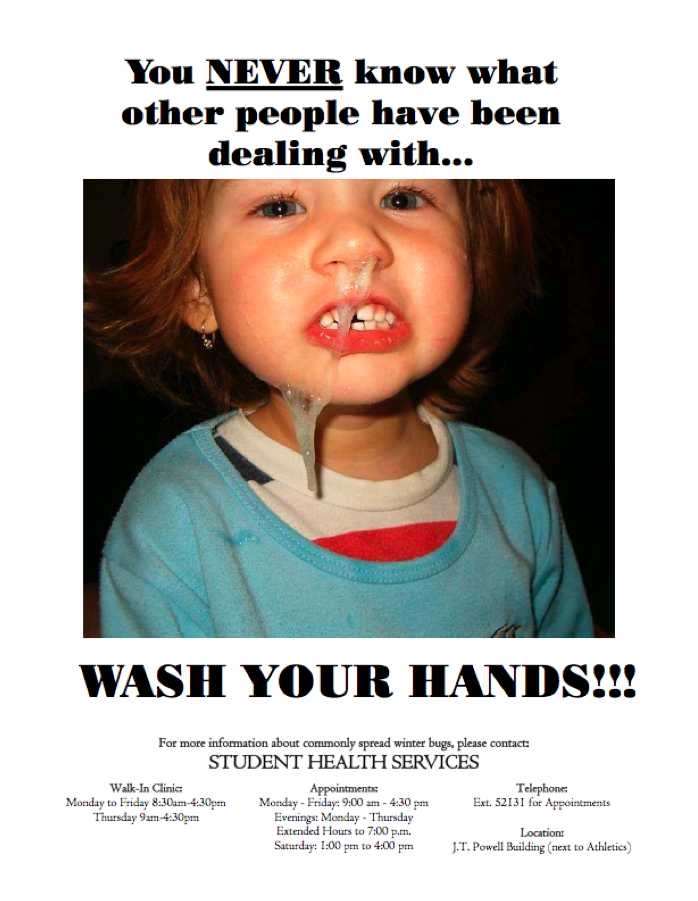

Dr. Curtis is involved in efforts in Africa, India and England to explore what she calls “the power of trying to gross people out.” One slogan that appeared to be effective in England in getting people to wash their hands before leaving a bathroom was “Don’t bring the toilet with you.”

Whatever the fine points of disgust, its power to affect behavior is unquestioned, and that power ought to be put to good use, Dr. Curtis said. So, in one of her projects, she has worked with an Indian public relations agency to come up with a disgust-based campaign to encourage hand washing among mothers in small villages, which could save countless children’s lives lost to diarrhea and other diseases.

The result, now being tested, is a skit involving two characters, one a supermom and the other a disgusting, dirty man. The man makes sweets using mud and worms, stops in the middle of the performance to rush off because he has diarrhea, never washes his hands and does everything possible to be revolting.

Supermom is scrupulously clean. Her children don’t get sick, the skit makes clear. In fact, her baby grows up to be a doctor. She washes her hands all the time.

The prominence of diarrhea in the skit is no accident. One thing about studying disgust, Dr. Curtis said, is that it makes you realize how important it is to talk about the very things that disgust us,  because they often present dangers to public health.

because they often present dangers to public health.

“We need to talk about” excrement, she said, using a punchier single-syllable word for maximum effect — a word she is unapologetic about using, as befits a disgustologist.

“Which is worse?” Dr. Curtis asked. To talk about it, “or to make kids die.

Shock and shame.

We’ve been using disgust for a long time. It is called barfblog.