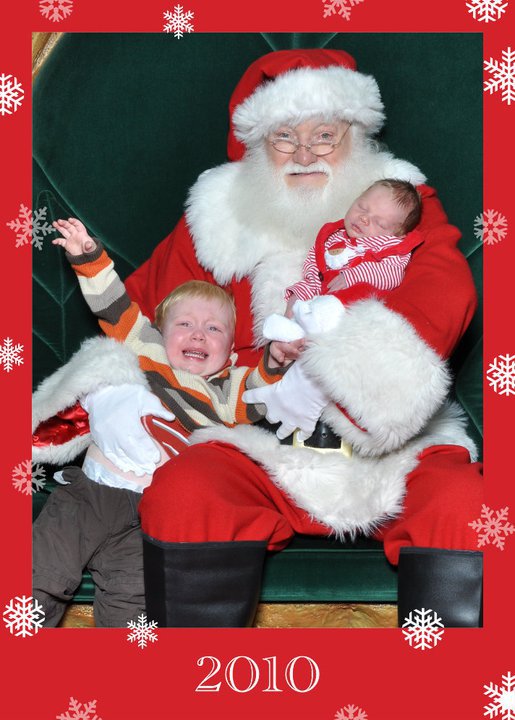

My wife and I have two little boys at home: a 2-and-a-half-year-old (Jack) and a 5-month-old (Sam)

I’m the neurotic parent, my wife is the calm one. Jack was a horrible sleeper for the first 16 months so anytime he didn’t make a noise for a couple of hours I’d wake up panicked and go into is room and see if he was breathing. I’m less paranoid the second time around.

I’m still pretty strict around foodborne risks though, cleaning the kitchen like a hospital after we’ve prepared any raw meats. I’ve got a cleaning and sanitation routine that includes multiple cloths, wipes and chlorine sanitizer. I’ve read too many stories about ill children — I want to make sure I do everything I can to reduce risks.

There are foods that we don’t expose our kids to as well — honey being one for Sam. There’s a pretty good chunk of evidence that it is a risky food for infant botulism in kids less than a year old. A couple of weeks ago, Richard Duplain, a beekeeper in New Brunswick wrote an op-ed in the aptly named Daily Gleaner challenging a current Health Canada campaign for infants to avoid eating honey. Duplain writes, challenging the imagery of the campaign is too harsh:

Displaying a honey bear bottle with a circle and slash through it with no valid explanation is irresponsible. According to the government department, less than five per cent of Canadian honey contains small amounts of C botulinum spores. Because even small amounts can cause infant botulism in a baby, health professionals advise against giving honey to children under one year old.

Neither the Minister of Health nor Health Canada provides any supporting evidence to buttress the false contentions asserted or suggested in the campaign.

Less than 5% still equates to 2.5 million lbs of Canadian honey that might be contaminated with spores. That’s a lot. And is in step with other worldwide estimates.

But then Duplain gets really weird:

There are two primary types of honey on the Canadian market. The first and best is raw unpasteurized honey and the second is low-quality pasteurized honey. To understand the pasteurizing process is to understand how C botulinum spores can survive in some honey.

Normally honey destroys bacteria by drawing fluids from them by osmotic force and through its acidity. Strained or unstrained raw honey contains an enzyme – glucose oxidase – which catalyses a reaction that produces hydrogen peroxide.

Hydrogen peroxide kills bacteria. Doctors and hospitals around the world are using honey dilutions as an effective antimicrobial and antibacterial agent.

However, this enzyme is destroyed by heat like that used in the pasteurizing process.

.jpg) Duplain also seems to be making the case that infants should be allowed to put honey on hurties (that’s what they are called in our house).

Duplain also seems to be making the case that infants should be allowed to put honey on hurties (that’s what they are called in our house).

Here’s where it would be useful for Duplain to throw his evidence and references on the table. From what’s out there it’s not clear that unpasteurized or pasteurized, imported or domestic are any different when it comes to suppressing spores.

C. botulinum that is protecting itself in a really tough protective shield (like the reflector shield from Return of the Jedi). Once the spores get into the digestive system of an infant, which hasn’t fully developed and has a gastric pH higher than 4.6, they can germinate and outgrow toxin. The rub, for the bee guys is that honey consumption is a factor in almost all infant botulism cases. There is also some evidence that infant botulism may be a risk factor for SIDS.

Health Canada, like the CDC in the U.S. both suggest that honey is an avoidable source of C. botulinum spores. The risk definitely outweighs the benefit for me.

Tragic stories around infant botulism have popped up over the past year. In Philadelphia Infant Amanda Zakrzewski was diagnosed with infant botulism and had to undergo 9 days of antitoxin treatment in hospital. Amanda wouldn’t eat, her eyes glassed over and she wasn’t able to suckle due to the paralysis the botulinum outgrowth caused. The result was months of rehab.

In the UK last year, a 16-week-old Logan Douglas was temporarily blinded and paralyzed from infant botulism. He fully recovered after six months, but at one point the illness was so severe that doctors had discussed turning off life support systems as the toxin was attacking his body. His mother revealed following the incident that she had fed Logan honey. She wasn’t aware that the food was a risk factor. Maybe a honey bear bottle with a circle and slash through it would have conveyed that message.