As an agency that prides itself on data – I guess that’s why it took 11 years to update the incidence of foodborne illness – I’m wondering, why did the U.S. Centers for Disease Control find it necessary to specifically finger consumers when it comes to food safety.

“CDC continues to encourage consumers to take an active role in preventing foodborne infection by following safe food-handling and preparation tips of separating meats and produce while preparing foods, (10).jpg) cooking meat and poultry to the right temperatures, promptly chilling leftovers, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cheese and raw oysters.”

cooking meat and poultry to the right temperatures, promptly chilling leftovers, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cheese and raw oysters.”

Why didn’t the CDC press release also say,

“CDC continues to encourage spinach farmers to keep cow poop off the produce.”

“CDC continues to encourage egg farmers to keep piles of poop away from fresh-market eggs.”

“CDC continues to encourage processors to cook the crap out of pot pies, pizzas and pet food that may sicken consumers (and their pets).”

“CDC continues to encourage retailers to sell food from sources that are known to manage food safety.”

“CDC continues to encourage restaurant-types to not let employees work while sick and to wash the damn poop off their hands before preparing salad.”

Consumers have a role. But the amount of cross-contamination that goes on in a home or food service kitchen means the contaminants have to be reduced before entering the next environment in the system, beginning on the farm.

Does CDC have meaningful data on where foodborne illness happens and whose fault it? We’ve published a paper on the silliness of blaming any particular group; the numbers simply aren’t there, and there are so many opportunities for contamination from farm-to-fork.

The FoodNet surveillance system was established within the U.S. Centers for Disease Control in 1995 to determine more precisely and to monitor better the  burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.

burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.

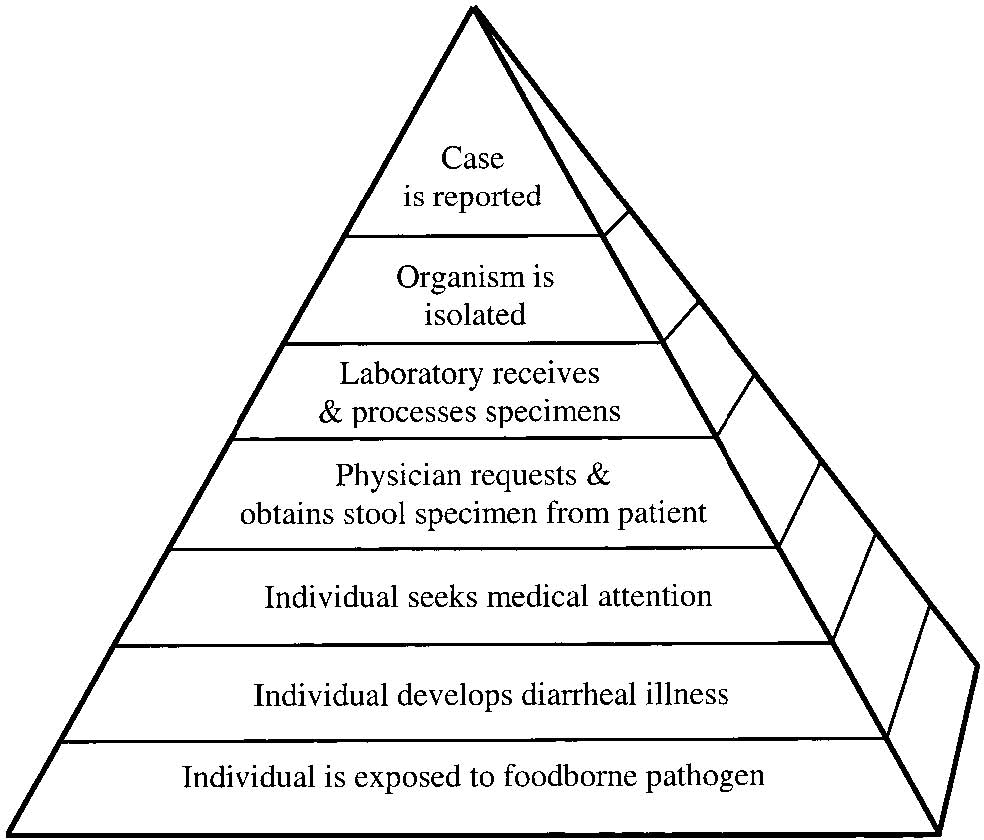

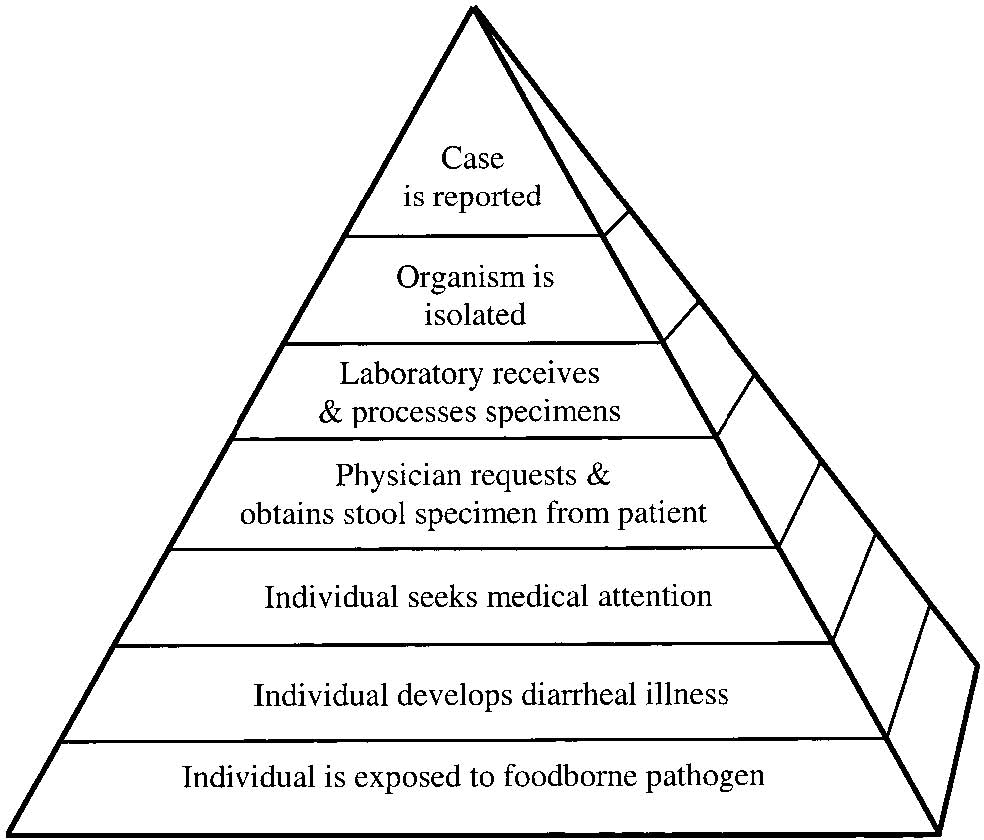

For every known case of foodborne illness, there are 10 -300 other cases, depending on the severity of the bug. Most foodborne illness is never detected. It’s almost never the last meal someone ate or whatever other mythologies are out there. A stool sample linked with some epidemiology or food testing is required to make associations with specific foods.

Foodborne illness is vastly underreported – it’s known as the burden of reporting foodborne illness, or the burden of illness pyramid (left), a model for understanding foodborne disease reporting. Someone has to get sick enough to go to a doctor, go to a doctor that is bright enough to order the right test, live in a State that has the known foodborne illnesses as a reportable disease, and then it gets registered by the feds.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimated that up to 30 per cent of individuals in developed countries acquire illnesses from the food and water they consume each year. U.S., Canadian and Australian authorities support this estimate as accurate, or did, (Majowicz et al., 2006; Mead et al., 1999; OzFoodNet Working Group, 2003) through estimations from available data, active disease surveillance and adjustments for underreporting. WHO has identified five factors of food handling that contribute to these illnesses: improper cooking procedures; temperature abuse during storage; lack of hygiene and sanitation by food handlers; cross-contamination between raw and fresh ready to eat foods; and, acquiring food from unsafe sources.

Food safety is much more than consumers.

Majowicz, S.E., McNab, W.B., Sockett, P., Henson, S., Dore, K., Edge, V.L., Buffett, M.C., Fazil, A., Read, S. McEwen, S., Stacey, D. and Wilson, J.B. (2006), “Burden and cost of gastroenteritis in a Canadian community”, Journal of Food Protection, Vol. 69, pp. 651-659.

Mead, P.S., Slutsjer, L., Dietz, V., McCaig, L.F., Breeses, J.S., Shapiro, C., Griffin, P.M. and Tauxe, R.V. (1999), “Food-related illness and death in the United States”, Emerging Infectious Diseases, Vol. 5, pp. 607-625.

OzFoodNet Working Group. (2003), “Foodborne disease in Australia: Incidence, notifications and outbreaks: Annual report of the OzFoodNet Network, 2002”, Communicable Diseases Intelligence, Vol. 27, pp. 209-243.

heated because you heard about other outbreaks and were concerned about liability?" She responded, "No. The stuff starts to smell when it’s a few weeks old and heating removes the smell."??

heated because you heard about other outbreaks and were concerned about liability?" She responded, "No. The stuff starts to smell when it’s a few weeks old and heating removes the smell."??.jpg) crucial that handwashing in young children should be supervised, especially after touching or petting animals or their surroundings on a visit to a farm."

crucial that handwashing in young children should be supervised, especially after touching or petting animals or their surroundings on a visit to a farm." general from 39 states.

general from 39 states.(10).jpg) cooking meat and poultry to the right temperatures, promptly chilling leftovers, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cheese and raw oysters.”

cooking meat and poultry to the right temperatures, promptly chilling leftovers, and avoiding unpasteurized milk and cheese and raw oysters.” burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.

burden of foodborne diseases and to determine the proportion of foodborne diseases which are attributable to specific foods and pathogens. Whatever criticisms and uncertainties exist, the establishment of FoodNet was revolutionary in better understanding the impact of foodborne illness.(9).jpg) 1999. That’s 47.8 million sickies instead of 76 million.

1999. That’s 47.8 million sickies instead of 76 million. treatment to save her life.

treatment to save her life..jpg) today, with nary a mention of thermometers.

today, with nary a mention of thermometers.

“We have two confirmed cases of E. coli O157:H7 in Jasper County. One of the cases resulted in a death.”

“We have two confirmed cases of E. coli O157:H7 in Jasper County. One of the cases resulted in a death.”