I’m a sucker for the cliche of anniversaries and today is sort of a big one for me. Ten years ago today I started pulling news in the Powell lab, seeking out the raw stories that made up listserv postings for the precursor to bites, FSNet. Pulling news then meant scouring newspaper websites and manually searching news wires for anything food risk-related. Now, we’ve got google alerts, twitter and RSS feeds.

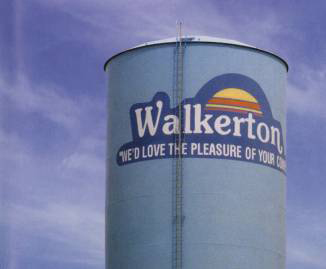

About three weeks in, I fell in love with the content and became hooked on food safety communication. That’s when an E.coli O157 outbreak linked to Walkerton Ontario’s town water system hit. I was already interested in disease (maybe it was because of Outbreak or the Hot Zone?), but the coverage and discussion within the Powell lab around Walkerton (how the outbreak was handled and communicated to the folks drinking the water) drew me in. The outbreak started with few reported illnesses and a boil-water advisory was issued. In the end, seven died, over 1300 were ill and many who have long-term health issues related to the outbreak will continue to feel the effects for years.

This weekend, a precautionary warning about the water supply in parts of Massachusetts reminded me of the Walkerton situation. Not so much the tragic aspects revolving around the illnesses, but issues like the best ways for public health officials to get information out to residents and how anyone making food deals with not having potable water.

According to Boston.com, a major water pipe which supplies Boston and about 30 other communities sprung a leak yesterday prompting a boil-water advisory for over two million residents, businesses and institutions.

Governor Deval Patrick declared a state of emergency and issued a "boil-water" order for the Boston Area "The water is not suitable for drinking. … All residents in impacted communities should boil drinking water before consuming it," he said at a news conference this afternoon. Patrick said the state had asked bottled water companies to make more water available in the state and emergency drinking water supplies could also be made available to the affected communities through the National Guard.

People flocked to stores to buy bottled water when they heard the news. In Lexington, an hourlong run on water cleared a supermarket’s shelves. In Boston, Mayor Thomas M. Menino declared a state of emergency and took a number of steps to inform residents, including reverse 911 calls and sending officers into the streets with bullhorns. Downtown restaurateurs declared the boil order a major inconvenience.