Daughter Sorenne woke up around 6:15 a.m. after a big Halloween night (thanks for the costume, Katie). Then the clocks on the computer changed and I realized it was 5:15 a.m.

Damn you daylight savings.

Damn you daylight savings.

So while Sorenne plays on the floor and fills her diaper, I’m looking at a poignant release from the France-based World Organization for Animal Health, inexplicably referred to as OIE (it’s a French thing) reiterating the importance of animal health rules to control human disease.

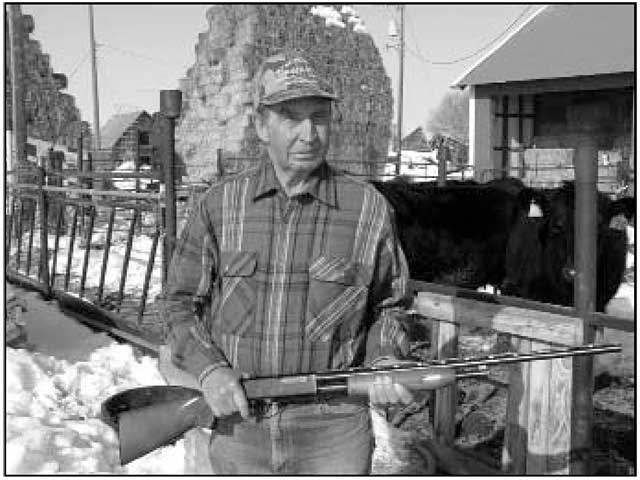

When the first case of bovine spongiform encephalopathy or mad cow disease was discovered in Canada in May, 2003, Alberta premier Ralph Klein famously declared that any

"self-respecting rancher would have shot, shovelled and shut up."

In 1184, city leaders in Toulouse, France, introduced some of the first documented measures to oversee the sale of meat: profit for butchers was limited to eight per cent; the partnership between two butchers was forbidden; and, selling the meat of sick animals was forbidden unless the buyer was warned.

By 1394, the Toulouse charter on butchering contained 60 articles, 19 of which were devoted to health and safety.

As outlined by Madeleine Ferrières, a professor of social history at the University of Avignon, in her 2002 book, Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, the goal of regulations at butcher shops — the forerunners of today’s slaughterhouse — was to safeguard consumers and increase tax revenues. Animals from the surrounding countryside were consolidated at a single spot — the evolving slaughterhouse, originally inside city walls — so taxes could be more easily gathered, and so animals could be physically examined for signs of disease.

As outlined by Madeleine Ferrières, a professor of social history at the University of Avignon, in her 2002 book, Sacred Cow, Mad Cow: A History of Food Fears, the goal of regulations at butcher shops — the forerunners of today’s slaughterhouse — was to safeguard consumers and increase tax revenues. Animals from the surrounding countryside were consolidated at a single spot — the evolving slaughterhouse, originally inside city walls — so taxes could be more easily gathered, and so animals could be physically examined for signs of disease.

It’s no different today: slaughterhouses are common collection points to examine animals for signs of disease and to collect various levies. And like medieval times, one of the most basic rules is animals that cannot walk are forbidden from entering (the slaughterhouse or city).

Veterinary legislation is a critical infrastructure element for all countries. In many OIE Member countries, the veterinary legislation has not been updated for many years and is obsolete or inadequate in structure and content for the challenges facing veterinary services in today’s world.

Dr Vallat says that it is important that the veterinary services have the authority to enter livestock premises and other establishments and take the actions needed for early detection, reporting and rapid and effective management of any animal diseases as soon as they are detected. Such actions include the capacity to seize animals and products, to impose standstills, quarantine, testing and other procedures; to control animals and products at frontiers; and to require the destruction and safe disposal of animals and all articles considered to present a risk of disease transmission and to public health. These activities represent the core activities of veterinary services in the field of animal health control and veterinary public health and the legislation must provide the necessary authority as a minimum.