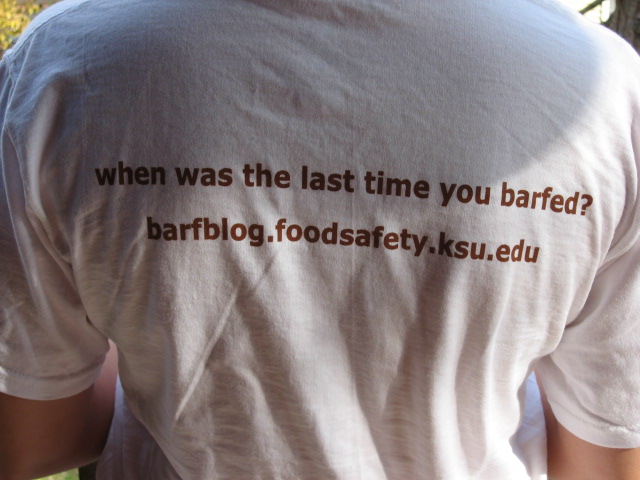

Since relaunching in May, 2007, barfblog.com (or barfblog.foodsafety.ksu.edu) has become an Internet success.

Since relaunching in May, 2007, barfblog.com (or barfblog.foodsafety.ksu.edu) has become an Internet success.

Two years ago, when I first came to Kansas, and met Amy, I wrote the following about barfblog and its intentions:

I’m convinced my mother tried to kill me through foodborne illness.

Not intentionally, of course.

But twice a year, on average while growing up, I’d spend a couple of days on the couch, passing liquid out of both ends, while mom comforted me with flat ginger ale, crushed ice (we even had one of those kitchen necessities — an ice crusher, in groovy pink, suitable for early 1970s suburbia) and soothing words like, "It’s just the flu honey, you’ll feel better soon."

As Lisa Simpson remarked upon hearing about the demise of her cat, Snowball, from her mother, "She lied, she lied."

The vast majority of such diarrheal episodes are not the mythological 24-flu, but food or waterborne illness. The World Health Organization estimates that up to 30 per cent of all citizens in developed countries will contract foodborne illness each and every year. That’s over 9 million Canadians, and that’s a lot.

It’s not that food is more dangerous now than in the past, it’s that scientists and others are increasingly able to connect illness with a certain bug in a certain food.

And for many of a certain age — early fourties or so — my story rings true; they either had vengeful parents or, more likely, suffered regularly from foodborne illness.

The worst was when I was 10 or 11. I was playing AAA hockey in my hometown of Brantford Ont., and we were off to an out-of-town game. My parents (bless them) usually drove, but obligations meant I had to get a ride with a friend on the team. About half-way to the arena, I started feeling nauseous. I tried to ask the driving dad to pull over, but it came on so fast, I had to grab the closest item in the backseat, an empty lunchbox.

I filled it.

And more.

Back in the 1970s, the coach’s main concern was that we win. I was the starting goaltender almost every game, while the backup sat on the bench. We had something to prove because we were from Brantford, the city that had produced Wayne Gretzky just a couple of years earlier and everyone was gunning for us.

I tried to get myself together to play. No luck. We got to the arena and I promptly hurled.

And again.

Obviously I couldn’t play, and, unfortunately, couldn’t go home. So the rest of the team went out for the game, as I lay on a wooden bench in a sweat-stenched dressing room, vomiting about every 15 minutes.

Such tales are not unique.

Whenever I spark up a conversation with a stranger, and they discover I work in food safety, the first response is: "You wouldn’t believe this one time. I was so sick" or some other variation on the line from American Pie II, "This one time, at band camp …"

But the stories of vomit and flatulence are deadly serious. Three weeks ago, a 5-year-old died in Wales as part of an E. coli O157:H7 outbreak that has sickened some 170 schoolchildren. Four people in the Toronto region were sickened with the same E. coli several weeks ago after drinking unpasteurized apple cider. Over 20 people are sick with the same bug from lettuce in the Minnesota area. And so it goes.

Canada needs to establish a set of clear, national objectives to reduce foodborne illness; we currently have none. The U.S. established such goals years ago, and while many can gripe about the validity of various statistics, at least the Americans have a national goal — a plan to work towards — while Canada continues its slide into complacency (on so many levels). In the absence of leadership, consumers can act by sharing their stories (visit barfblog.com) and proving that they, the victims of foodborne illness in its

many dreadful forms, have a voice. They can demand more.

Demanding more means sourcing food from safe sources, and that means asking questions. In many cases of foodborne illness, whether involving my mother or today’s cooks, the fault lies at the farm, the distributor, the processor, or anywhere along that farm-to-fork food safety chain. Consumers have a role in preparing safe food, but not nearly as big as those so-called educational programs targeted solely at consumers would suggest.

How did my game end? I could hear the various cheers but was lost in dizziness and nausea and sweat, wondering when this would end.

The trip home was uneventful; I was drained — figuratively and literally.

We lost.

That version of barfblog was more of a message board and got swarmed with porn spam. So we shut it down. Then Bill Marler provided access to some custom software and barfblog was reborn. Yeah Bill.

That version of barfblog was more of a message board and got swarmed with porn spam. So we shut it down. Then Bill Marler provided access to some custom software and barfblog was reborn. Yeah Bill.

From pot pies to pepperoni to peanut butter, Douglas Powell, scientific director of the International Food Safety Network at Kansas State University leads a team of undergraduate and graduate students who want to make food safety a pop-culture phenomenon and change the way the world thinks about food. Through barfblog, they comment daily on food safety happenings including such categories such as celebrity barf and the "yuck" factor.

We’ll get some T-shirt order forms sorted out later today.