Roy Stevenson was a senior quality controller for more than a decade at one of the UK’s largest poultry abattoirs, in Scunthorpe, until the end of 2012 when he was made redundant. Owned by the 2 Sisters group, the factory still supplies many leading supermarkets and fast-food chains. After the Guardian investigated this factory and others this year to understand why so much chicken across the industry was contaminated with Campylobacter, Stevenson decided to come forward. He wanted to explain what is was like when he worked there, and why there can be such a gap between what auditors see and what workers feel is the reality on the factory floor

The government’s food watchdog has been forced to admit that an initial inquiry which cleared one of the UK’s largest poultry processing plants of hygiene failings was misleading.

The government’s food watchdog has been forced to admit that an initial inquiry which cleared one of the UK’s largest poultry processing plants of hygiene failings was misleading.

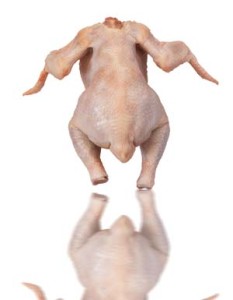

Instances of chickens being dropped on the floor then returned to the production line, documented by a Guardian investigation into failings in the poultry industry, constituted a “breach of the legislation”, the Food Standards Agency has now acknowledged.

Following the Guardian revelations at the site in Scunthorpe in July, the health secretary, Jeremy Hunt, asked the FSA to investigate. It rated the factory as good and wrote to the shadow food and farming minister saying there was no evidence of any breaches of food hygiene legislation.

But in an embarrassing climbdown less than a month on, the FSA has written to Labour’s Huw Irranca-Davies admitting it was wrong. It has reviewed the Guardian’s undercover footage showing dirty birds from the floor being thrown back into food production and concluded there has been a serious breach. But it has not issued a penalty, saying the company has assured it the problem has been addressed.

The admission comes as fresh allegations of hygiene failings at the factory emerged, with three former employees making claims about dirty chickens contaminating the production line and attempts to manipulate inspections up to 2012.

Labour said the FSA admission and the new questions over safety raised serious questions about the poultry inspection system in the UK.

But now three workers who have been in charge of quality control at the factory in recent years have come forward claiming it was “an almost daily occurrence” for birds to fall on the floor and be put back into the food chain instead of being correctly disposed of as waste. The company initially denied any instances of this happening.

The sources also claimed that auditors were often hoodwinked, even when their visits were supposedly unannounced, as managers slowed production lines and cleaned up poor practice when they were present. One described his responsibility for ensuring production managers followed the company’s own rules on food hygiene and safety as “a war of attrition”.

The three new sources were all employed as quality controllers until 2012 at the Scunthorpe site. Roy Stevenson was in charge of a team of quality assurance technicians and worked at the factory for more than a decade until being made redundant at the end of 2012.

The three new sources were all employed as quality controllers until 2012 at the Scunthorpe site. Roy Stevenson was in charge of a team of quality assurance technicians and worked at the factory for more than a decade until being made redundant at the end of 2012.

“On the day of the audit, all the lines would be slowed to a minimum where it was pristine,” he claimed. “There would be no birds dropping on to the floor, an auditor would walk round and everything would look lovely, unlike any other day.”

Richard Lingard worked at the factory as a quality controller for a few weeks in 2012 before moving on because he said it was impossible to do the job correctly. A third former quality controller with several years’ experience at Scunthorpe in the recent past, who asked for anonymity, described being regularly undermined and bypassed when trying to enforce hygiene rules.

All three claimed birds fell on the floor regularly because the line speeds were too fast for workers to keep up, and they would then be recycled back into the food chain in breach of company policy. They allege that their efforts to stop this happening were undermined by production staff.

In response, 2 Sisters said audits could not be cheated and it had no way of knowing when unannounced ones would take place.

Audits and inspections are never enough: A critique to enhance food safety

30.aug.12

Food Control

D.A. Powell, S. Erdozain, C. Dodd, R. Costa, K. Morley, B.J. Chapman

Internal and external food safety audits are conducted to assess the safety and quality of food including on-farm production, manufacturing practices, sanitation, and hygiene. Some auditors are direct stakeholders that are employed by food establishments to conduct internal audits, while other auditors may represent the interests of a second-party purchaser or a third-party auditing agency. Some buyers conduct their own audits or additional testing, while some buyers trust the results of third-party audits or inspections. Third-party auditors, however, use various food safety audit standards and most do not have a vested interest in the products being sold. Audits are conducted under a proprietary standard, while food safety inspections are generally conducted within a legal framework. There have been many foodborne illness outbreaks linked to food processors that have passed third-party audits and inspections, raising questions about the utility of both. Supporters argue third-party audits are a way to ensure food safety in an era of dwindling economic resources. Critics contend that while external audits and inspections can be a valuable tool to help ensure safe food, such activities represent only a snapshot in time. This paper identifies limitations of food safety inspections and audits and provides recommendations for strengthening the system, based on developing a strong food safety culture, including risk-based verification steps, throughout the food safety system.

COFCO signed the agreement with food safety service firm AsureQuality and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) on the sidelines of the APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation) leaders meeting in Beijing, said a statement from PwC’s New Zealand office on Monday.

COFCO signed the agreement with food safety service firm AsureQuality and PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) on the sidelines of the APEC (Asia Pacific Economic Cooperation) leaders meeting in Beijing, said a statement from PwC’s New Zealand office on Monday.