Duke (or Dook as it’s known around here) is waging war on multiple fronts this week: with John Wayne’s estate over bourbon, and with the equally powerful yogurt community over nuances of pathogenicity.

Here’s the shortened story: Chobani receives complaints associated with yogurt coming out of one of their plants: packages were bloating and popping. Some customers experienced a gross-out factor that led to barfing (I get that, I gag when I take the garbage out sometimes). A fungal contaminant, Mucor circinelloides, associated with spoilage and generally not considered a foodborne pathogen is found in the plant and product. Duke researchers obtain some of the organism from an opened bloated yogurt container in Texas. They culture the organism and test it on mice human cells and says that the fungus is more dangerous to rodents and humans than we thought.

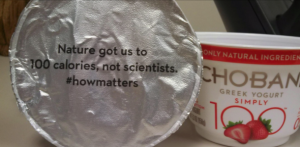

In unrelated news, Chobani says no science is involved in yogurt-making.

Food Quality News reports that the paper has led to some excitement in the food safety world.

Dr Alejandro Mazzotta – the microbiologist heading up food safety at Chobani – says he is disappointed by the publication of a “highly irresponsible” paper in the peer-reviewed journal mBio alleging that the fungal contaminant found in some of its yogurts last fall was a potentially dangerous food borne pathogen.

Speaking to FoodNavigator-USA on Tuesday, Chobani’s VP quality, food safety, and regulatory affairs Dr Alejandro Mazzotta said he was surprised that the paper made it through the peer review process owing to what he claimed to be its flawed methodology, poor use of citations, and general “lack of scientific rigor”, and for drawing conclusions that are not supported by the evidence presented.

Randy Worobo, was cited as saying “While the data indicate that the isolates can cause disease when injected directly into the bloodstream of mice – at a level of 1 million Mucor circinelloides per mouse – this type of experiment, while interesting, obviously does not reflect natural exposure through foods.

Asked to respond to these comments, the mBio study co-authors Dr Soo Chan Lee and Dr Joe Heitman from the Duke University Medical Center were cited as saying “The murine models employed in our study are standard ones used frequently by investigators to study the virulence potential of microbes in an animal model. These studies, and similar ones of related isolates, show that this fungal species is a pathogen in mice capable of causing lethal infection via this route of infection… The inocula used was fully appropriate for this model.

Lee and Heitman state that “Mucor circinelloides f. circinelloides is the “most virulent M. circinelloides subspecies and is commonly associated with human infections,” and it’s unclear whether this statement is based on the literature (which isn’t referenced) or their findings which were arrived at with just three mice.

Between the lack of negative controls; the use of rodents as a human model (with the high doses of 10^6 organisms); and the lack of detection of the pathogen in feces (just relying on symptoms); there are some flaws in the approach.

Food safety folks in the industry tend to get nervous about messy food safety-related public discussions believing that the public won’t understand the details. Discourse like this is (and the data behind it) is necessary to aid shoppers in making informed choices.